In the middle of October last year Karim Khan KC, the chief prosecutor at the International Criminal Court (ICC), took a call from one of the lawyers in his office. But the hour-long conversation wasn’t about the most challenging case they were working on, against the Israeli prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu. It was about allegations that had been made against Khan himself.

The man tasked since 2021 with trying the most serious human rights abuses in the world had been accused of molesting a woman in his office. And the person on the other end of that phone call was his alleged victim.

“Be wise… We're in shark-infested waters,” the prosecutor told her in a recording that has been leaked to The Observer.

Months earlier, in floods of tears, the woman had confided to colleagues that for almost a year, Khan, 55, had been allegedly molesting her in his office and engaging in non-consensual sex with her in hotel rooms during work trips abroad. A friend of hers says that she recounted how she “would just lie there. One time [she] even pretended to be asleep”. Afterwards she would vomit, she told people.

Friends say she was afraid of Khan, who she said would freeze her out if she tried to resist his advances. The position she held in his department was her dream job and she was sure that if she tried to report the alleged abuse, her career would be over.

The colleagues in whom she confided felt the matter was so serious that they had to relay her allegations to the Independent Oversight Mechanism(IOM), the official body that investigates claims of wrongdoing at the ICC.

Within days, however, the IOM closed the case without any further action, recommending minimal contact between the woman and Khan, while leaving her to continue working in the same office. But journalists had started asking questions. It looked like someone at the ICC was leaking details of the allegations to the media.

The phone call between the pair lasted more than an hour, during which Khan asked about her wellbeing and urged her to take as much time away from the office as she needed. But the conversation kept returning to the topic of her allegations and whether she would be willing to state categorically that there was no truth to them.

Related articles:

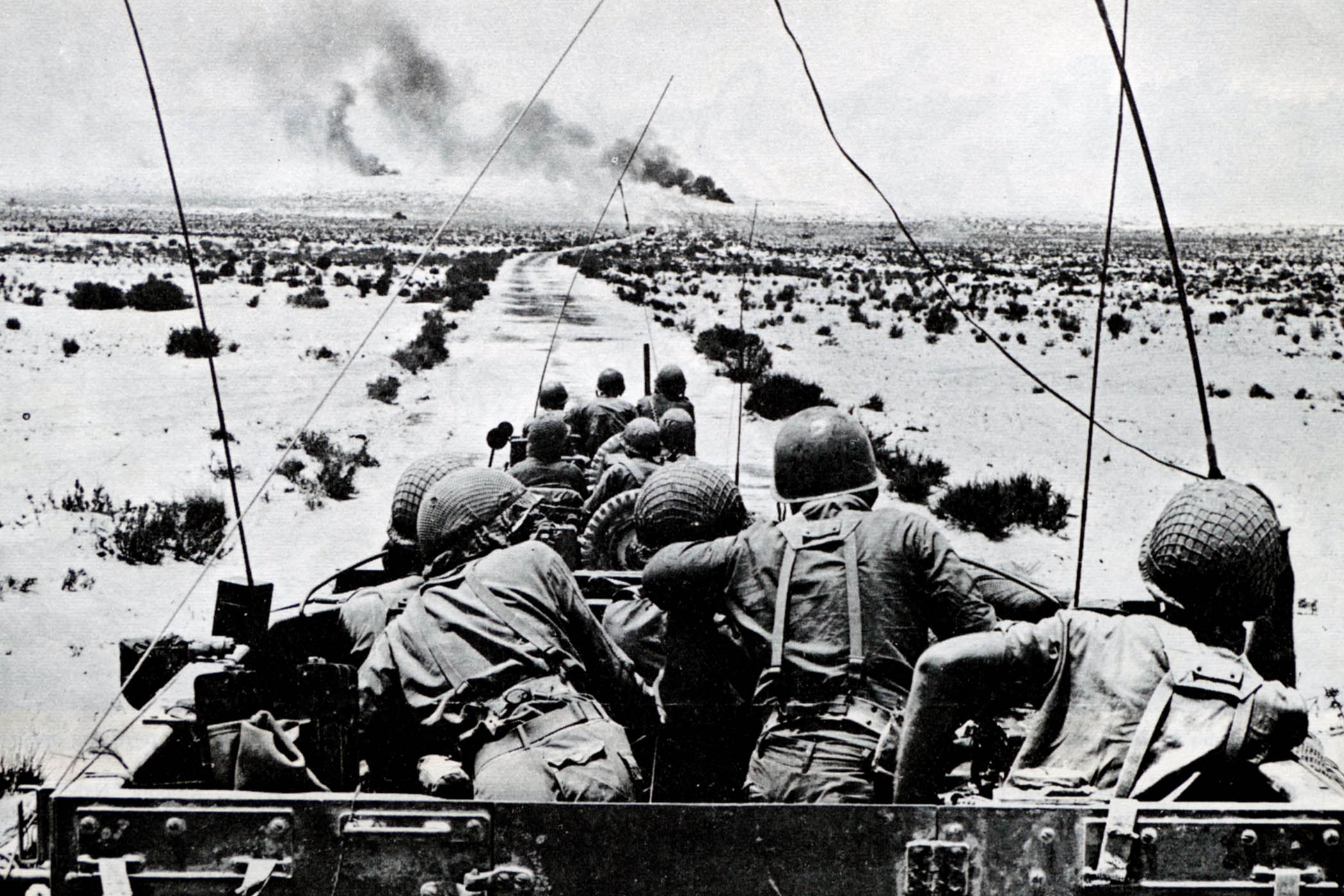

Ukraine’s former prosecutor general, Iryna Venediktova, and Khan visit a mass grave on the grounds on the outskirts of Kyiv on 13 April 2022

“ If we contain this, if we behave logically, there’s nothing to report,” he told her. “ One option you’ve got is to just write… ‘I have no intention of making any complaint, this matter is closed and I want now to be left to do my work’,” he said. “Do it for [your son’s] sake.”

The allegations against Khan could not have come at a worse time – the court was already in the most vulnerable position since it had been established in 2002. Last November the ICC issued arrest warrants for Netanyahu, his defence minister Yoav Gallant and the Hamas military commander Mohammed Deif, who is thought to be dead. The warrants for the Israeli politicians sparked a torrent of fury from Jerusalem and from Israel’s supporters in the US and Europe. Since then Khan has been sanctioned by Washington, with his bank accounts and email access frozen.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Other senior staff at the ICC have received anonymous threats and been warned they may also be sanctioned – in at least one case, the stress involved led to serious health issues. As a result, there has been a flurry of resignations. Some of those who have left told The Observer that they were too worried about retaliation to consider speaking publicly.

But while some have quit because of the threat of sanctions, others have left because of the allegations against Khan, including Purna Sen, his special adviser on working climate, which includes sexual abuse in the workplace.

Is the institution strong enough to withstand those two things, the US sanctions and a sex scandal, at the same time?

Is the institution strong enough to withstand those two things, the US sanctions and a sex scandal, at the same time?

Senior ICC staff member

Sen told The Observer that she was not surprised that the alleged victim did not want to come forward with her claims against the chief prosecutor. “ There is a culture where hierarchy and power are centrally important in how the organisation operates,” she said. “The most senior people are almost untouchable in such organisations. I would argue that it is actually irrational to report [sexual abuse]. Making a report is a very costly thing to do. Look at what has happened [to the alleged victim] as a result of this coming to light. Look how she’s paid for it.”

Since her allegations were made public, the woman at the centre of the sexual abuse claims has been labelled unhinged, obsessed with Khan and even an agent working for Mossad, the Israeli security service. Friends say her career as an international lawyer is over.

Through his lawyer, Khan told The Observer that it was categorically untrue that he committed sexual misconduct of any kind, whether molestation or non-consensual sex. They accused The Observer of stitching together a series of comments from entirely different parts of the phone conversation, presenting “a grossly misleading” representation of his words and their context. His lawyers say that it was the chief prosecutor himself who called for an investigation into the allegations.

Khan is said to believe that the claims against him are part of a plot to damage his investigation into alleged Israeli war crimes in Gaza, and some of those around him believe Mossad could be responsible. The British barrister has told friends that he’s paying the price for doing his job. His supporters say Khan is continuing the best tradition at the ICC of challenging the violent abuse of power.

But critics argue that he should have done more to protect the Gaza case by stepping aside and putting more distance between his personal situation and the work of the court. Even the ICC’s biggest supporters now fear that the allegations against Khan and the US campaign against the institution could spell the end for the world’s only permanent war crimes court, established half a century after the Nazi trials at Nuremberg and in the wake of the failed tribunals in Yugoslavia and Rwanda.

In the weeks after Hamas’s attack on Israel on 7 October 2023 and Israel’s subsequent war on Gaza, Khan came under enormous pressure to open an investigation into alleged war crimes. He and his team visited the kibbutzim that were attacked and spoke to the families of hostages. And he was planning an unprecedented visit to Gaza to speak to Palestinians affected by Israel’s military action and gather evidence.

As soon as Khan started to investigate Gaza, the ICC began receiving an almost constant stream of Palestinian and Israeli supporters lobbying on both sides of the conflict. An ICC insider says there are very real threats and Khan was told by security officials at the court that the Israeli intelligence agencies were “actively focused on him”.

An investigation by the Guardian last year revealed a history of Israeli intelligence attacks on the court – reporting that the head of Mossad had personally threatened Khan’s predecessor, Fatou Bensouda, over her investigations into alleged Israeli war crimes in the occupied Palestinian territories.

But this time the threats against the chief prosecutor also came from official sources. As Khan’s investigation was reaching its conclusion last May, he took a conference call from a group of US officials from both sides of the political divide. An ICC employee who was on that call has told The Observer that Republican senator Lindsey Graham, a staunch supporter of Israel, “got extremely excited… he was very angry” and threatened Khan with sanctions if he proceeded with the case against Netanyahu.

Yoav Gallant and Benjamin Netanyahu

When Khan announced his application for arrest warrants very publicly on CNN, Netanyahu labelled the decision “antisemitic”, while the Israeli president Isaac Herzog said it was a “dark day for justice and humanity”. The then US president Joe Biden called it “outrageous” and criticised the prosecutor’s decision to announce the arrest warrant for the Hamas commander at the same time. “Whatever the ICC might imply, there is no equivalence – none – between Israel and Hamas,” he said.

Speaking to The Observer between crisis meetings at The Hague, the court’s first chief prosecutor, Luis Moreno Ocampo, says those lobbying the court on Israel’s behalf have made political arguments. “They say Israel is my friend, Israel is a democracy. But they are not saying Israel is not starving the people of Gaza.” Moreno Ocampo believes Biden was aware that cutting aid to the territory was a war crime and that is why the US went to such great lengths to bypass Israel’s blockade by dropping food parcels and building a pier to deliver food by sea to Gaza.

The pressure on Khan and the ICC has only increased since Donald Trump returned to power. Days after taking office, the president signed an executive order setting out extensive sanctions against Khan. These measures threatened to fine and even imprison any individual, organisation or company providing Khan with “financial, material, or technological support”. The upshot is that his British bank account and his credit card have been frozen. When he tried to send his ex-wife money for his children from his bank in Holland, the funds were blocked when they arrived in the UK and he has not been able to get them back. Even access to his email has been blocked by Microsoft forcing him to change to Proton Mail, a Swiss company.

Meanwhile, the US extended the sanctions this week to four ICC judges from Uganda, Peru, Benin and Slovenia. Two were responsible for authorising the arrest warrants for Netanyahu and Gallant, and the other two had authorised an ICC investigation into abuses by US military personnel in Afghanistan. The US secretary of state, Marco Rubio, said the judges had engaged in efforts to prosecute nationals of the United States or Israel without their consent. Neither the United States nor Israel is party to the ICC’s Rome Statute but the organisation claims the right to investigate crimes committed by non-member states if they took place in countries that have signed up to the court – such as Palestine and Afghanistan.

Packages of aid land in Gaza

Danya Chaikel, who is the ICC representative for FIDH, a federation of NGOs, warned that the sanctions could have a chilling effect, “that enforcing accountability for mass atrocities can get you punished”.

The British Foreign Office issued a statement condemning the extension of sanctions and saying that the court must be permitted to do its work. They recently warned scores of lawyers, officials and academics who have worked with or advised the ICC – including Lord Justice Fulford, Baroness Kennedy and Amal Clooney – to take pre-emptive measures because of the likelihood that they may also be sanctioned. Since then some organisations and NGOs have reportedly stopped working with the ICC due to fears they may face consequences in the US if they are seen to be supporting the court.

There is also a far worse scenario: the US could in future extend sanctions to the institution itself, preventing banks and software companies such as Microsoft – which currently provides the database for all the evidence stored at the court – from dealing with the ICC as a whole. An ICC insider told The Observer: “ If the court as a whole gets sanctioned, then you are looking at a complete meltdown of the system.” Former ICC judge Cuno Tarfusser said that “if [the US] do that, then the court is finished.”

While the US is alone in implementing sanctions, the ICC has also faced the prospect of other nations refusing to comply with the Israeli arrest warrants. The organisation has been described as a giant with no arms or legs – a body with no enforcement capabilities, reliant on its 125 member states to arrest suspects.

Germany’s new chancellor Friedrich Merz has said he wants to “find a way to ensure that he [Netanyahu] can visit Germany and leave again without being arrested”. However, Moreno Ocampo dismissed the idea: “It’s impossible to think that German judges would not order the arrest of Netanyahu, it’s just not possible.”

He accuses of hypocrisy western nations that say they want an international rules-based system but in practice fail to deliver, creating “one law against our adversaries, like Putin, but we don’t use the law against ourselves or our friends like Israel”.

But there is another concern in western capitals: that Khan may have issued the arrest warrants before he had gathered enough evidence in order to prevent the allegations about his own behaviour becoming public.

Khan and his team had worked for months behind the scenes to secure an unprecedented trip for the chief prosecutor to Gaza at a time when almost no international organisations were being granted access.

His team believed that images of the chief prosecutor walking through the rubble would send a critical message to victims around the world that the ICC cared enough to visit a war zone. The Observer has spoken to several ICC employees involved in organising the trip and they all say that Khan’s visit to Gaza would have been important for the court’s standing and reputation and could have helped gather evidence that would have been important if the case were brought to trial.

A former ICC staffer who worked on securing the trip says it was a difficult process and Khan had gone to the very top to help him negotiate for the access he needed. “You’re not talking to some diplomat at the US embassy, okay? You are asking [the US secretary of State Antony] Blinken to do the negotiations. This is big game, right?” says the ex-staffer.

What had convinced Blinken to assist with those negotiations was a promise from Khan that during the trip he would be collecting significant amounts of evidence. It would take months to process it before any arrest warrants would be issued, he had said. Khan knew that both the US state department and Israel were playing for time: the US because they were worried that arrest warrants might mess with their negotiations for a ceasefire in Gaza; and Israel because the government there hoped to halt the case against Netanyahu altogether.

Joe Biden is welcomed by Netanyahu in Tel Aviv on 18 October 2023

A foundational principle of the ICC is that it only operates as a court of last resort and so would be forced to step aside if a state were willing and able to handle any war crimes allegations themselves. Netanyahu was reportedly in discussion with the Israeli attorney general about the possibility of appointing a committee to investigate alleged crimes in Gaza, something that could have derailed the ICC investigation.

It may be that Karim Khan is guilty of sexual abuse, and there may also have been ways in which that was used to try and undermine him

It may be that Karim Khan is guilty of sexual abuse, and there may also have been ways in which that was used to try and undermine him

Stephen Rapp former US ambassador-at-large for war crimes issues

Khan’s special adviser Tom Lynch was due to fly to Jerusalem to put the finishing touches to the prosecutor’s itinerary. But the evening before his flight Khan called Lynch and told him not to take the flight. He didn’t explain why. The next day Khan appeared on CNN saying that he had submitted the Israel files to the judges.

Friends of Khan say the prosecutor told them that two months earlier, he had warned US state officials that he intended to announce the application for the warrants and that a letter required for any advance planning by the ICC team with the United Nations department of security services was promised but never issued by Israel. He believed the discussions for the trip were not “being undertaken in good faith by Israel”. Khan says he is still keen to visit Israel and Gaza and to engage with all parties.

But Khan’s critics point out that Blinken and many senior colleagues in his inner team hadn’t been informed about the submission in good time and were blindsided. Some wonder about the timing given the case was handed to the judges just weeks after the sexual abuse claims first surfaced.

From his apartment in The Hague where he has now taken a leave of absence, Khan has been waiting for the results of a fresh investigation into the allegations of sexual misconduct against him. While it’s continuing he is restricted from giving interviews to the media but tells friends he can prove the allegations are untrue.

The Wall Street Journal published an article last month ithat linked the timing of the request for Netanyahu’s arrest warrant with the case against Khan and raised questions about whether the chief prosecutor was aiming to protect himself from the assault allegations. Khan complained to friends that the newspaper had access to evidence he hadn’t seen.

One friend who has been in touch with Khan throughout this crisis says the prosecutor believes there is a plot against him by a few ICC employees who are operating at the behest of the state department and Mossad.

Despite the fact that his alleged victim is Muslim and had an exemplary record at the ICC for years before Khan arrived at the court, staff in the chief prosecutor’s office say he engaged with the idea that she might be linked to an Israeli plot. “ Very early on, he put out the narrative that she was a Mossad and kind of ran with it,” says a former ICC staffer.

The whole affair, Khan is convinced, is part of a concerted effort by the Israeli government and its supporters in the US to try to discredit him. If they succeed, he believes, these kinds of intimidation tactics will continue to be used against whoever takes over from him as the next ICC chief prosecutor. “Next time they will just warn them, we will do a ‘Karim’ on you,” he told a friend.

Some people believe the chief prosecutor should not have allowed himself such close contact and private calls with someone who had made serious claims about him – whatever was being said in the calls.

Sen, Khan’s former special adviser, says that if the phone call to the alleged victim was genuine then it brought into question the chief prosecutor’s ability to continue in the role. “ If true, that is not just a lapse of judgment, but an abuse of power and of course completely unethical. Whether or not it is career-ending depends on what the court decides to do with this information, because we know very many powerful men across the world have been protected, and their careers have continued unhindered.”

Stephen Rapp, a former United States ambassador-at-large for war crimes issues and a big supporter of the ICC, said the accusations against Khan have created a perfect storm. “Both may be true. It may be that Karim Khan is guilty of sexual abuse, and there may also have been ways in which that was used to try and undermine him and take advantage of any issue they have to weaken the pressures to comply.”

Rapp is at pains to point out that the ICC judges clearly felt the case against Netanyahu was strong enough to issue an arrest warrant.

An ICC lawyer who worked on the Gaza case told The Observer that it was reckless of Khan not to step aside much earlier to allow a proper investigation into the allegations against him. “A lot of good work has gone into [the Gaza] case, a lot of victims who put their confidence in the court. And now, it’s inextricably intertwined – his personal scandal, and the case [against Netanyahu] when they didn’t need to be connected at all,” they said.

Some senior staff at the court have questioned if these crises might combine and result in the end of the organisation. “Is the institution strong enough to withstand those two things, the US sanctions and a sex scandal, at the same time? I think a lot of people are concerned about that,” they said.

Khan’s supporters say that he deserves a chance to answer the allegations against him. “The point is that he has submitted himself to a legal process now – Netanyahu has not,” a friend said.

Moreno Ocampo believes that the real danger to the court is the climate of fear that has been created within the prosecutor’s office. Right now Khan’s deputies are preparing cases against two more senior Israelis, the minister for national security Itamar Ben-Gvir and the finance minister Bezalel Smotrich for alleged crimes committed against Palestinians in the West Bank.

“Will they chicken out?” Moreno Ocampo asks. “Because this is bigger than Khan. The survival of the court and its ability to function is about building a world with law and order and with controls on violence. What’s at risk is civilisation itself.”

Additional reporting by Serena Cesareo

Photographs by Fadel Senna/AFP via Getty; Dimitar Dilkoff/AFP via Getty; Amos Ben-Gershom/GPO/ Handout/Anadolu Agency via Getty; Abood Abusalama/Middle East Images/AFP via Getty; GPO/ Handout/Anadolu via Getty