In his art-filled office, his large frame hunkered into a dark leather armchair, Edi Rama, the Albanian prime minister, speaks of “the gloom” that has descended on Europe.

Voted back into office for a fourth term in May and with the Balkan nation winning plaudits for its progress in EU accession talks, the leader is not having a bad year. Yet he is perturbed by “the lack of positive energy all over the place”, and by the sense that the continent is somehow coursing, despite the “great people” who lead it, deeper into gloom.

“I don’t see the light,” he says. “There is this gloom in Europe and I don’t see the way out of it. There are people trying to do the right [thing], but I don’t see a strategy. It doesn’t help to think that the problem is elsewhere. It is in Europe. It is us.”

A painter before he went into politics, Rama exudes the air of a professor who, though contrarian and alternative – his raffish style includes a penchant for hand-painted ties – has managed through dint of grit, talent and charisma to bring wide-ranging reforms to the once hermetically sealed communist state.

In Brussels, the 61-year-old socialist is regarded as one of the most pragmatic leaders to have emerged from the former east. In Tirana, EU ambassadors praise Rama’s creative ability “to think out of the box” even if endemic corruption continues to plague the country and, recently, the highest levels of his own government. The admiration might explain why Rama’s outlook is taken seriously.

‘Europe itself is out of balance, its bureaucracy outweighs its politics, and its internal quarrels loom larger than its shared horizon’

‘Europe itself is out of balance, its bureaucracy outweighs its politics, and its internal quarrels loom larger than its shared horizon’

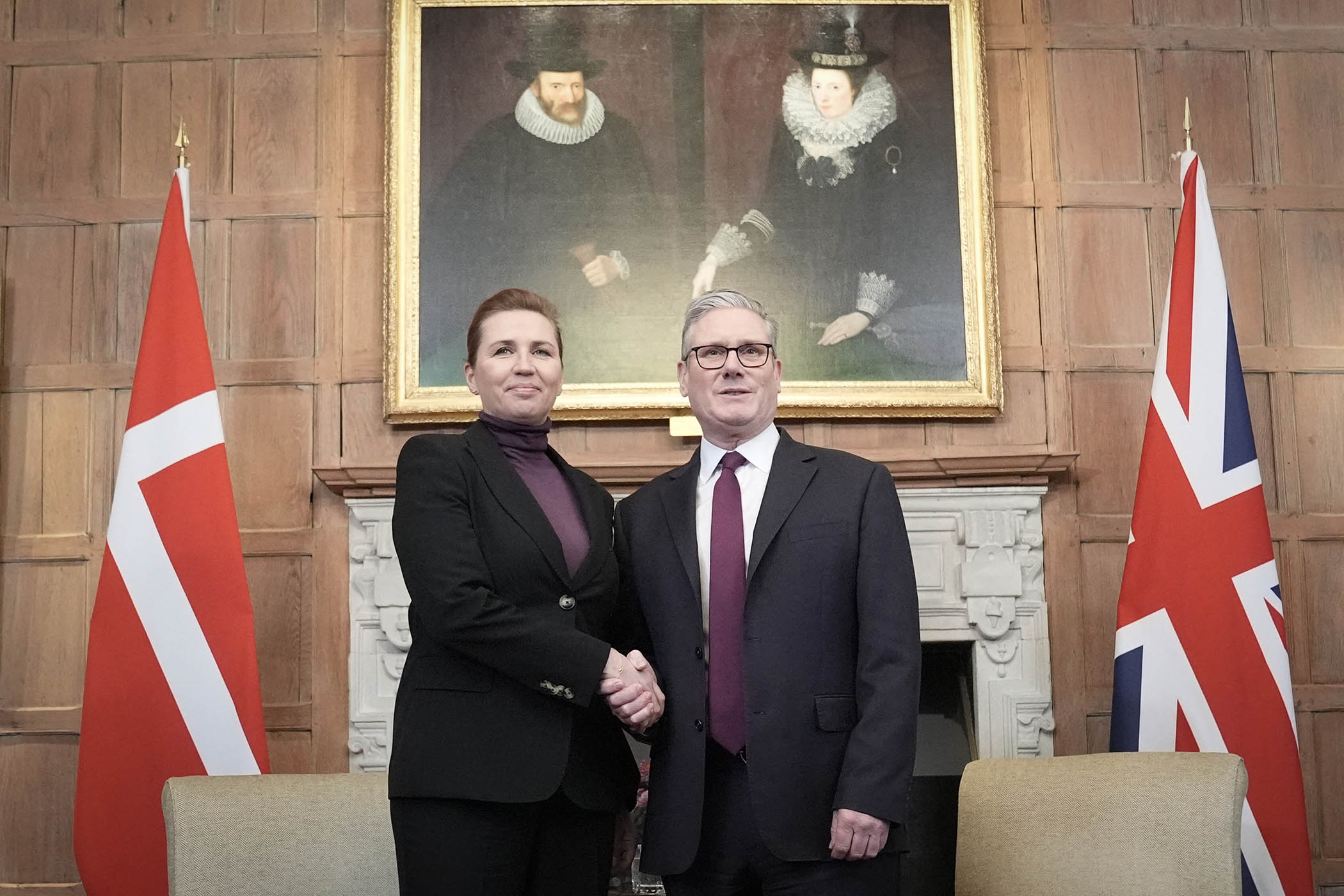

The migration debate has been especially challenging for an Anglophile politician forced, yet again, to denounce the “ethnic stereotyping” of Albanians by a British home secretary. He doesn’t hide, in a wide-ranging interview with The Observer, how “unsettling” it is that this time accusations of Albanians abusing asylum laws have been made not by a Tory minister, but under a Labour government led by a man with whom he has “very good” relations.

“If you single out a community, you can expect members of that community to be hurt, assaulted, wounded, beaten up,” he says, his fingers moving back and forth through a set of worry beads. “We know from history that this is what happens.”

France’s socialist party had committed “spectacular suicide”, he said, because it had tried to emulate the rhetoric of the far right on the issue of immigration. It was a cautionary tale for leaders to keep to their convictions and values.

Related articles:

“When you get into the game of competing with the far right, you lose, for the simple reason that when it comes to choosing who is tougher on issues like migration, the instinct is to go with the original, not the copy,” he says. “You think you can dance with the devil? Well, the devil wins the moment you step on to the floor.”

The rise of the populist far right, patriotic nationalism, divisiveness and Europe’s accelerated drive to militarise are among the potent forces Rama believes are exacerbating the gloom.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

But Rama has never subscribed to the view that the US president, Donald Trump, is Europe’s problem; nor does he think the new US national security strategy is particularly surprising.

Instead, he sees Trump’s election as a wake-up call; the jolt needed to shake Europe out of the inertia that is holding it back. For too long, he says, the EU has been detached from reality and hobbled by its own bureaucracy.

“The wisdom of the world has grown a lot out of our sight, and suddenly we are realising that we are behind,” he says. “In this time of great challenges, we lack political strength, we remain on the surface, when depth is what the moment demands.”

The bloc’s cumbersome bureaucracy is a key impediment. “Europe itself is out of balance, its bureaucracy outweighs its politics, and its internal quarrels loom larger than its shared horizon.”

If the continent is to become stronger, there should be “more Europe, not less Europe” and more soul searching regarding policies and actions that could be setting it back.

“It is about strategic thinking and right policies and where we want Europe to be in 10 or more years time,” he says. “More of the same is not a strategy. Europe has to change, and it has to change fast. Everyone is saying it, everyone is aware of it and yet everyone else is moving at a much faster speed.”

From the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Albania, which joined Nato in 2009, has thrown its weight behind the alliance. Indicative of its enthusiasm for what Rama calls the “only morally viable position” is a license plate prominently placed outside his office, emblazoned with the word Ukraine and embellished with red hearts.

‘Get us into Europe, and I am ready to sign an agreement stating clearly that we don’t want to have [the power] of a veto’

‘Get us into Europe, and I am ready to sign an agreement stating clearly that we don’t want to have [the power] of a veto’

In the former Stalinist state there is no love lost for today’s Russia, even if Albanian intellectuals profess a fondness for Russian literary greats that were read and taught until the country’s ruthless dictator, Enver Hoxha, cut ties with Moscow.

“Every human who is interested in the world cannot but love many things about Russia,” Rama adds. “But not Russian politics. In Albania we certainly don’t miss not having any business with Moscow since 1960.”

Six months after Putin launched his Ukraine invasion in February 2022, municipal authorities in Tirana renamed the boulevard on which the Russian embassy stood “Free Ukraine Street”, making clear any mail would be directed to the new address. The diplomatic mission was quickly forced to relocate.

Yet Rama is also critical of the way Europe has handled peace negotiations, crediting Trump for reaching out to Russia and bringing “something new and important to the game”.

“He brought communication and diplomacy in the middle of a war that might have been the first ever with no communication,” he says. “OK, he did it in a disruptive way because that is how he does it, but here again, is a question for us: what are we doing?

“How come Europe has never had a peace plan, or direct communication with Russia? Is it normal for who we are as Europeans? I don’t think so.”

In the void, he said, Putin had been able to succeed – “as the brutal chess player that he is” – in fuelling a psychology of fear of further attacks when, in reality, Russian troops had spent years trying to seize Ukraine’s Donbas region.

The invasion has highlighted the geopolitical imperative of incorporating the western Balkans into the 27-member bloc.

Rama readily admits that in wanting to join the EU, Albania has been forced “to swallow a lot of frogs” in terms of punishing and sometimes nonsensical reforms.

But membership is also existential. After more than 500 years as a backwater on the periphery of the Ottoman Empire and nearly five decades subjected to the isolationist rule of a communist regime more brutal than any other, no quest is more resonant of success than this.

Geography, say those still old enough to remember, may have ensured they were European, but Hoxha’s cruelty and paranoia also meant Albanians never felt part of the continent.

Decades of turbulent transition following the regime’s collapse has only reinforced the bloc’s appeal. Of all the candidates waiting at Brussels’ door, no country has higher support for EU accession than Albania. The fervour partly explains why Rama has 2030 in his sights for accession, with talks concluded by the end of 2027. It’s a goal derided as “wildly unrealistic” by his political opponents but the 6ft 6in leader appears determined to do whatever it takes.

“Get us into Europe, and I am ready to sign an agreement stating clearly that we don’t want to have [the power] of a veto,” he says. “We will never use our vote against the majority. We don’t even want our own commissioner. We can make an agreement with Italy and Italy’s commissioner can be our commissioner.

“We’re ready to do this as a safeguard against any fears that some crazy guy from the Balkans will want to get into the club with the power of a veto and start imposing things.”

Photograph by Helena Smith