In Tehran, even under a rain of missiles, people find each other. That’s the image emerging on Iran’s fractured, unstable internet. Among those is Bahman, a bookseller in central Tehran. Each evening, he posts late-night updates from his shop – cafe lights still flickering, cigarettes passed under taped windows, strangers exchanging meaningful nods. Another social media user wrote: “The city is wounded, but still breathing – together.”

These snapshots capture more than defiance. They speak of a fragile intimacy, a country turning inward to hold itself up.

And yet, while the people huddle in the dark, the man who rules them does so alone – and in hiding. Ali Khamenei, Iran’s supreme leader, has never seemed so exposed. For decades, he built a regime sustained by ideology, fear and the myth of invincibility. That myth now lies in ruins. His most trusted commanders are dead. His enemies grow bolder. And even fear-wrought loyalty is eroding. He no longer governs a country. He commands a bunker.

In the early hours of Saturday morning, US Air Force B-2 stealth bombers were tracked heading west across the Pacific. Officials told Reuters the US was moving the bombers to the island of Guam as President Trump weighed whether to take part in Israel’s war against Iran.

By Saturday evening he had made that decision, announcing in an address from the White House that the US had targeted three nuclear sites in Iran and “completely and fully obliterated them”.

Israeli airstrikes have already eliminated more than 20 senior figures from Iran’s military and intelligence elite – among them Mohammed Said Izadi, who was responsible for Iran’s ties to groups including Hamas.

They weren’t just top brass – they were Khamenei’s confidants. The men who built his security state and enforced its will. Their sudden absence has exposed the fragility of the system he once claimed would endure beyond him.

‘It’s amputation. He’s lost the people who protected both his body and his narrative’

‘It’s amputation. He’s lost the people who protected both his body and his narrative’

“This isn’t just attrition. It’s amputation,” one Persian-language analyst wrote. “He’s lost the people who protected both his body and his narrative.”

Khamenei’s initial response to Israel’s strikes was silence. For days, nothing. Then, last Wednesday, a pre-recorded video was released – brief, static and unsettling. The sound echoed as though in an empty room. There were no edits. The lighting was harsh. And under his robe, a conspicuous bulge suggested a bulletproof vest.

Social media users filled in the silence: “He’s too frightened to allow a trusted crew near him,” one wrote. “This isn’t a leader. This is a man in hiding.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

He has reason to be.

Last week, Israeli defence minister Israel Katz said that Khamenei couldn’t “continue to exist” if Israel is to achieve its goals. It marked a dramatic shift – not only in Israel’s military rhetoric, but in the existential pressure now bearing down on the Islamic R Republic’s top figure. The message wasn’t coded. It was unmistakably personal.

And it landed. Since last summer’s assassinations of Hamas’s Ismail Haniyeh in Tehran and Hezbollah’s Hassan Nasrallah in Beirut – both central to the Islamic Republic’s regional strategy and presumed to be protected – the regime has spiralled into paranoia.

Families of military personnel have been instructed not to click on unknown links or open suspicious text messages – a sign of how deeply the regime fears cyber-infiltration and remote assassinations.

Meanwhile, Iran has been digitally severed. The regime’s longstanding plan for a “national internet” – technically cutting the country off from the global web – has been deployed in full force. Information from inside the country is scarce. VPNs are blocked and messaging apps restricted. The Islamic Republic has long used its domestic internet infrastructure not only to filter content but to isolate Iranians during moments of unrest – a tactic driven by both fear of foreign influence and of domestic dissent.

The regime’s propaganda machine has gone into overdrive. In a surreal twist, the IRIB news channel aired footage of the Bagheri Chitgar residential complex, which had been struck in north-west Tehran, and falsely presented it as part of Iran’s attack on Israel.

It was unmistakably Iranian soil. And worse: the original video, published earlier on social media, included the sound of Persian being spoken. In the broadcast version, the audio had been muted, a sign this was not a mistake but deliberate misinformation, aimed at deceiving the public.

“They’re trying to show us we’re winning, while we’re the ones burying the dead,” one viewer posted

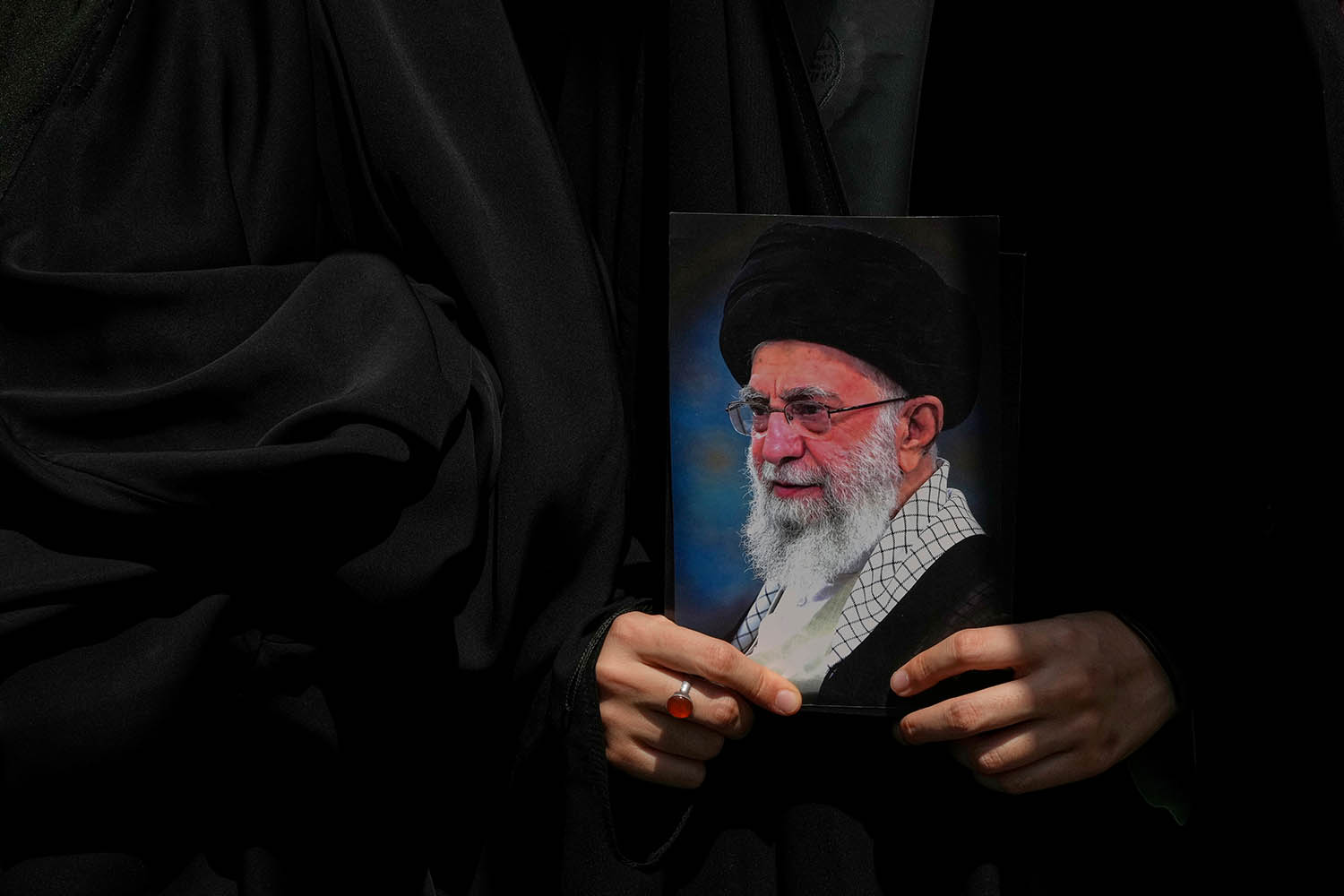

An Iranian holds a poster of the Ayatollah Ali Khamenei during a protest to condemn Israeli attacks on cities across Iran

Perhaps most telling is Khamenei’s shift in rhetoric. Even though he has long seen himself as the spiritual leader of Shia Muslims across the globe – his legitimacy deriving from divine guardianship – when fear creeps in, his language changes. It is no longer about God. It is about the “nation”. It is about survival.

In previous elections, when turnout plunged to historic lows, he urged citizens to vote “even if you don’t support the government”. Now, in his second pre-recorded video, he did it again. Speaking in urgent tones, he praised “the great people of Iran” who are “resisting the oppressors” – the very same people his regime has imprisoned, surveilled, beaten, and executed over the past 35 years.

“It’s almost tragic,” said one Iranian activist in exile who asked not to be named. “He’s built a state on religious absolutism, but now that it’s crumbling, he reaches for the very people he’s spent his life trying to control.”

It’s not repentance. It's desperation.

Diplomatic fatigue

Negotiations in Geneva on Friday with European powers concluded without a definitive result. Masoud Pezeshkian, Iran’s president, said his country would not stop its nuclear activity – but was “ready for dialogue and cooperation to build trust regarding peaceful nuclear activities”.

Iran’s foreign minister, Abbas Araghchi, met Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan for diplomatic talks in Istanbul.

For all his isolation, Khamenei appears still to believe that diplomacy might offer a face-saving way out of the pit he has dug himself into. These talks – fragile as they are – suggest he has not entirely given up on a negotiated escape. But time is short.

Outside Iran, the regime’s orbit is collapsing. Haniyeh and Nasrallah are gone. Although Vladimir Putin, the Russian president, has publicly cautioned against any attempt at regime change or assassination, Khamenei knows he is not a man to trust. In fact, many in Tehran recall how Putin chose not to save Bashar al-Assad’s government in Syria until the eleventh hour – and only when it best served Moscow’s interests. Today, Russia eyes a future with Donald Trump, not Ali Khamenei. China, meanwhile, remains diplomatically neutral. – urging de-escalation and speaking vaguely of regional peace, but offering no real cover. Even within the region, Iran’s influence is visibly receding.

At home, Khamenei’s heir apparent – his son Mojtaba – inspires little confidence. And although yesterday the New York Times reported that Khamenei had named three senior clerics to replace him should he be killed, the clerical elite is increasingly fractured. The Revolutionary Guard, once monolithic, is now bruised, diminished and rattled.

Pro-regime rallies were staged on Friday in a few cities. They were likely orchestrated in part by state networks and the crowd’s slogans were tired.

Khamenei’s base has been eroding for years. Not just because of war, but because of the corruption of those closest to him, the deteriorating economy and what many view as his soft, confused response to Israel’s strikes and assassinations prior to the war.

“People see him blinking now,” said Faranak, an Iranian journalist in exile. “He looks like a tired old man clinging to something that’s already gone.”

In one of his latest online posts, Bahman, the bookseller, wrote: “Still here. Still open. We’re alive. We still have tea.” It’s not bravado. It’s resilience. A quiet insistence on being human – even as the state dehumanises.

The regime still arrests women for hijab violations. It still blocks VPNs and jails dissidents. But these acts now feel hollow, desperate – the gestures of a government acting out its past because it can no longer imagine its future.

The Islamic Republic may not fall this week, or next. But something has broken. The spell is gone. Khamenei cuts the figure of a man displaced by time – a supreme leader with no command, and no one left to truly follow. He is still in power. But power is no longer belief. It is no longer a myth. It is no longer enough.

Images by Atta Kenare/Getty and Vahid Salemi/AP