The Medical Research Council's Max Perutz award is a science communication competition, supported by The Observer, that recognises PhD students’ ability to explain to a non-scientific audience why their research matters. This year's prize was won by Vanessa Drevenakova of Imperial College London, for this written entry, and by Johnny Tam of the University of Edinburgh for his short video on using speech technology to allow motor neurone disease patients to take part in clinical trials.

If I told you that a gentle pulse of sound could help keep your brain young, would you believe me? Not music. Not meditation. But carefully controlled sound waves, delivered deep into the brain. No surgery. No drugs. Just vibrations – measured, focused and silent to the ear.

I know it might sound far-fetched. But the idea that we could delay brain ageing itself with ultrasound might no longer be science fiction. In fact, it’s exactly what I am researching.

We’re living longer than ever before, but not necessarily better. Dementia is now one of the leading causes of death in the UK. Families are caring for loved ones who slowly fade in front of their eyes. And our treatments? They come late and do little to reverse the damage.

That’s why we need new approaches. Not just to manage decline, but to prevent it. Not to treat disease after it steals someone’s memories, but to protect the brain while there is still time.

I study what happens to the brain as we grow older, and how we might stop some of those changes, using ultrasound. Not to live for ever. Not to become superhuman. Just to remain ourselves for a little longer. Because ageing doesn’t just change our faces and joints. It changes the brain. Quietly at first, misplacing a word, forgetting a detail. Then more deeply. A friend’s name disappears. A routine becomes confusing. And, for some, even familiar faces begin to feel distant.

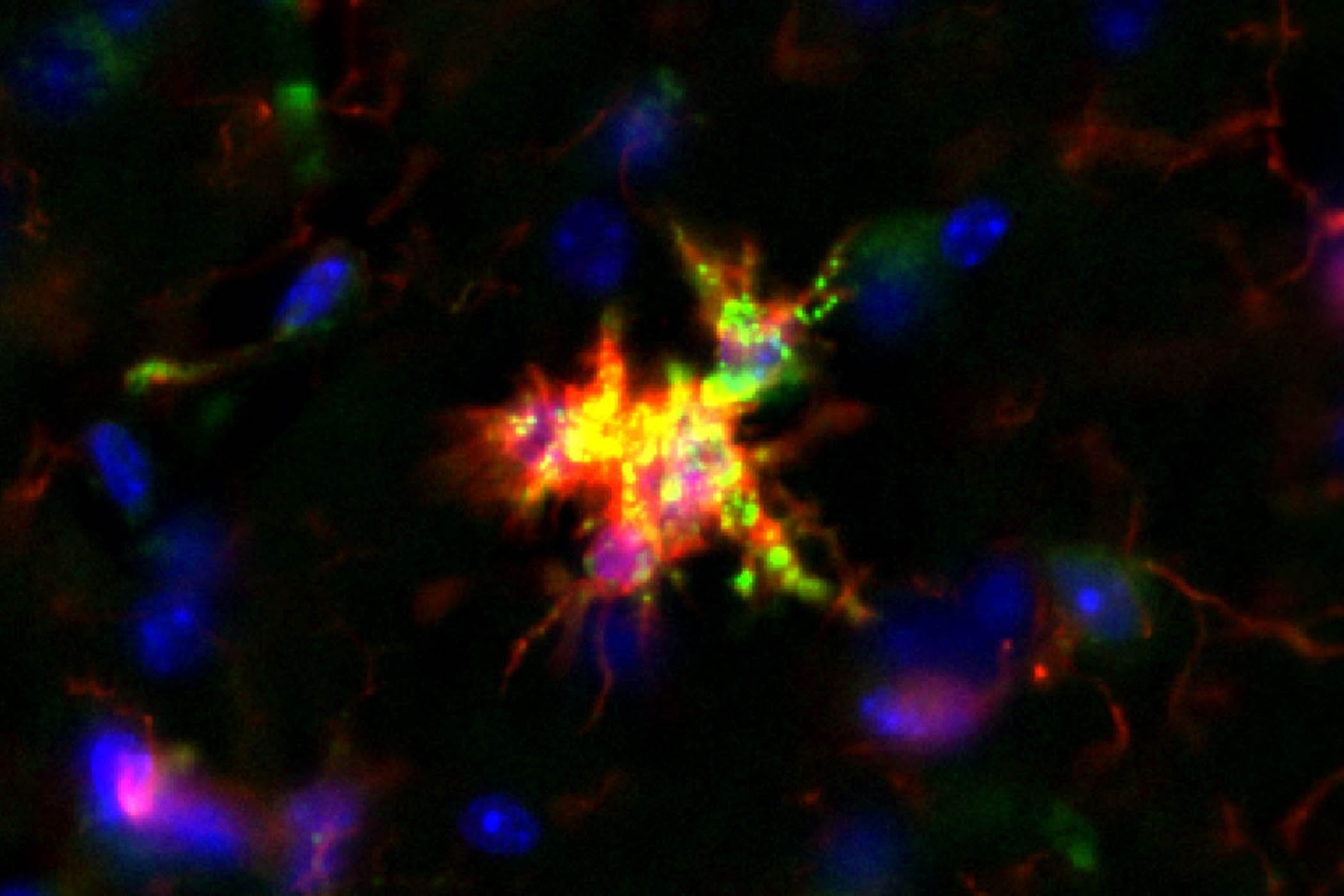

For a long time, we thought brain ageing was just slow decay – neurons wearing out, fading away. But now we know the story is more complex. The brain isn’t just a tangle of neurons. It’s more like a garden, constantly maintained by a team of microscopic caretakers, working tirelessly behind the scenes. These caretakers are microglia, the brain’s immune cells. They prune unnecessary connections, clear debris, and quietly patrol for anything out of place.

One of their most important jobs is to clear out proteins that naturally build up between cells.

In a healthy brain, these are swept away like fallen leaves. But when too many are left to gather, they can form the plaques and tangles seen in diseases like Alzheimer’s.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

With age, some microglia begin to falter. They don’t disappear, but they stop doing their job well. Scientists call these dysfunctional cells “senescent”. Instead of clearing out waste, they start adding to it. They release harmful signals, trigger inflammation and confuse the surrounding cells. This damages the connections between neurons, interfering with the brain’s ability to form and retrieve memories. Over time, these changes contribute to declines in learning, memory and overall cognitive function.

This is where ultrasound comes in. We’ve all heard of ultrasound. It’s what expectant parents see in their first blurry photo of a baby. But the ultrasound I use is a little bit different.

It’s focused. And focused ultrasound allows us to target precise areas deep inside the brain, using sound waves that converge like sunlight through a magnifying glass. What’s even better is that it’s safe and non-invasive. You don’t hear it. You don’t feel it. But the brain does.

Ultrasound is made up of tiny vibrations, waves of pressure moving through the body. Brain cells like microglia are coated in tiny molecular sensors, like trapdoors that respond to these pressure waves. When ultrasound reaches them, it nudges these doors open, allowing a rush of calcium inside. That calcium acts like a spark, igniting a chain reaction inside the cells – prodding them out of their idle daze and reminding them of their original purpose. Of course, inside the cell, this chain reaction is far more complex, unfolding through a cascade of molecules, genes and proteins that work together to regulate how the cell behaves.

Sound, like anything powerful, must be tuned carefully. Too little and nothing changes. Too much and the delicate cells of the brain may become overstimulated. That’s what makes it exciting – we can adjust the ultrasound signal to shape the cellular response.

I study how this process works in aged brain cells, especially microglia. My research asks whether we can encourage these senescent microglia to behave more like their younger selves: active, protective and calm. I watch how they move under the microscope, track the signals they send and test the chemical messages they release to see if their behaviour is changing.

Can a few pulses of ultrasound reduce inflammation in the brain? Can we help microglia support brain function and slow down memory loss? And can we do all of this without drugs, just using ultrasound?

Early findings suggest we can. After a single session of ultrasound, microglial behaviour shifts to be more attentive and responsive – their inflammatory signals quiet down, their clean-up systems switch on and their shape changes.

But it’s not about turning back time. It’s about restoring balance. If we can learn how to gently nudge the brain back on track, before too much damage sets in, we could delay or reduce the impact of age-related diseases like Alzheimer’s.

At the moment, my research is in the pre-clinical stage, working with animal models, testing how microglia respond, refining how one day ultrasound could be used to keep the brain in balance. And the potential is enormous. In just the past few years, focused ultrasound has moved from niche technology to clinical reality. In fact, it is already being tested in patients with Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. In our lab, we’re exploring whether it could take things even further – whether ultrasound might help us intervene earlier, by targeting the root causes of brain ageing before symptoms ever appear.

There is so much to explore. How long do the effects last? Can we reach the right cells without affecting the wrong ones? Are aged microglia as easy to shift as younger ones?

These are the questions I ask every day. Not just out of scientific curiosity, but because behind every result is someone’s story: a daughter trying to reconnect with her mum, a carer stretched to the edge, a family hoping for more time. And in some way, I carry those hopes with me too. They remind me every day why I love this research.

My PhD is part of a wider shift in how we think about brain health – not just in terms of treatment, but of timing. About how we care for the brain before decline sets in. About keeping the garden tended, the balance steady, the spark alive.

Ageing begins in silence. Perhaps healing can too.

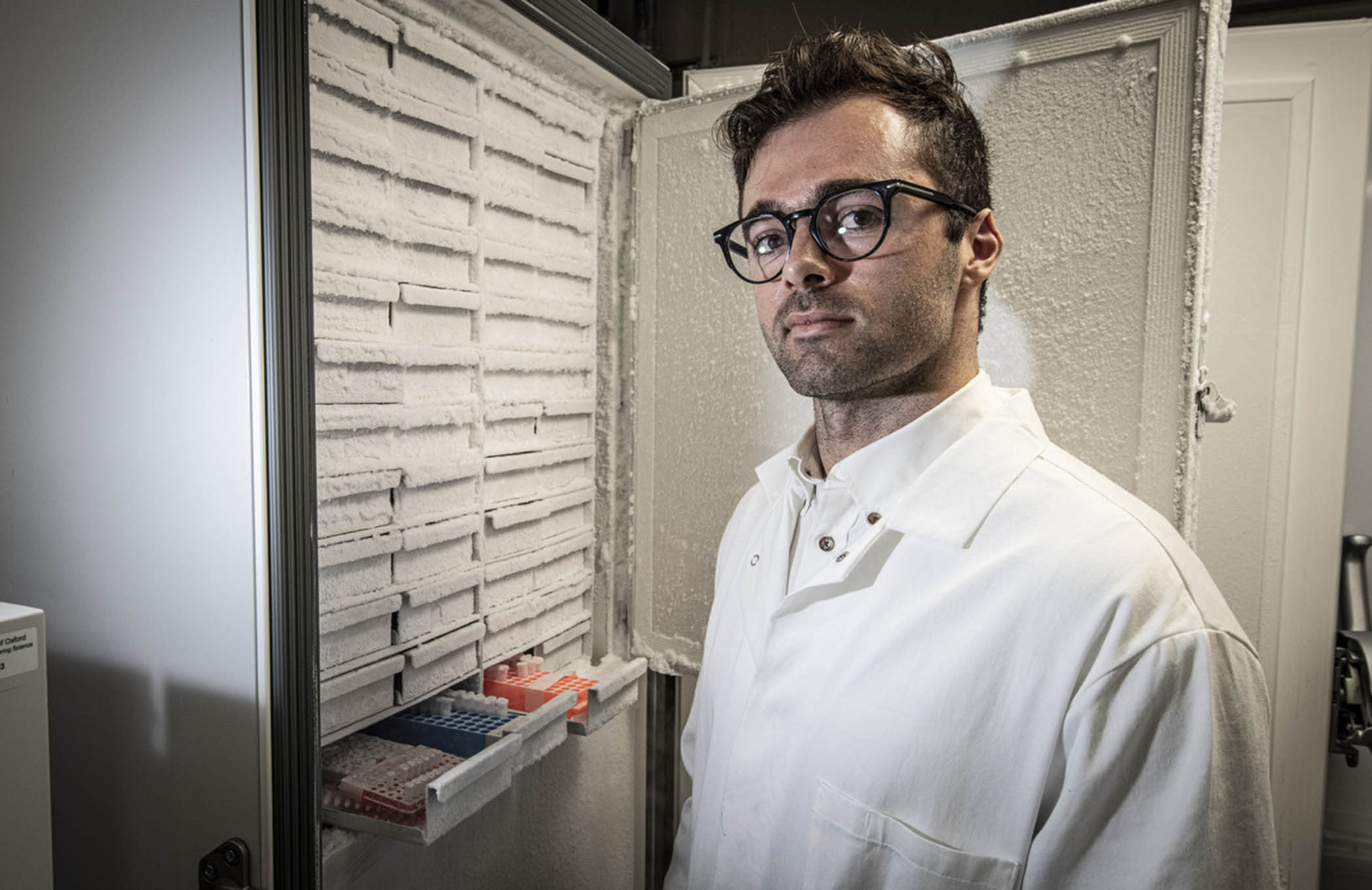

Johnny Tam with Steven Barrett, the MND patient who narrated his winning video