Gordon Brown was almost the only person in Britain to whom last weekend’s shocking revelations that Peter Mandelson had betrayed him, his party and his country did not come as a surprise.

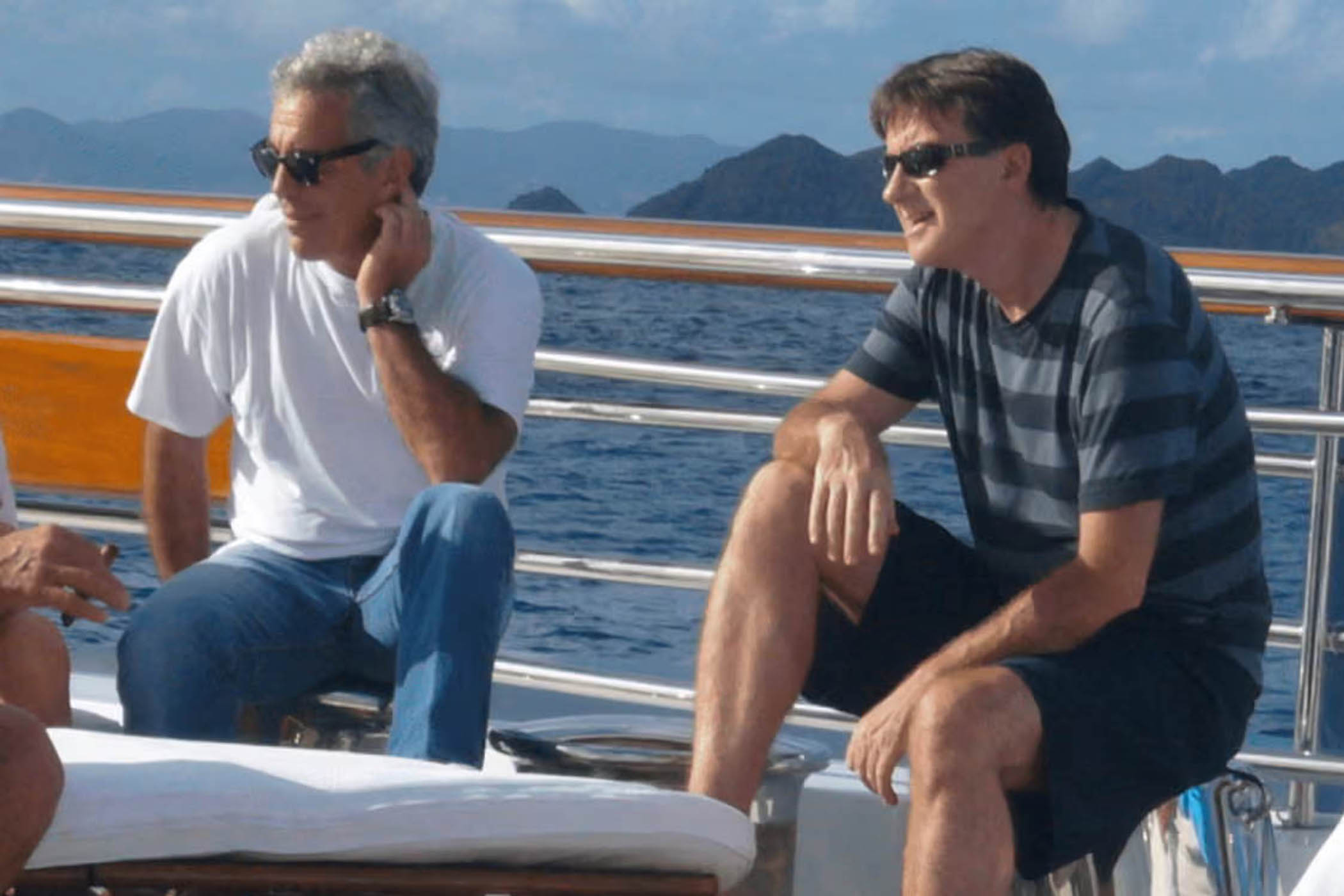

Mandelson is alleged to have leaked market sensitive information to the convicted paedophile and financier Jeffrey Epstein when he was business secretary in Brown’s government.

The scandal, worse than the Profumo affair in the early 1960s, has rocked the government and spells the end for Keir Starmer, whose fate, alongside that of his overrated chief of staff, Morgan McSweeney, is irrevocably tethered to Mandelson’s.

Starmer knew about Mandelson’s links to Epstein when he appointed him US ambassador last year. The move was pushed hard by McSweeney, of whom Mandelson has reportedly said: “I don’t know who and how and when he was invented, but whoever it was, they will find their place in heaven.”

But Brown, who once influenced Starmer to the extent that last year’s U-turn on the two-child benefit cap was down to pressure from the former prime minister, took last weekend’s news in his stride.

At his home, with panoramic views of the Firth of Forth in North Queensferry, Fife, there can be no mistake: he is incandescent with rage. But he knew this revelation of betrayal of trust and alleged corruption was coming, and he knows there is more to come.

After all, last September, Brown had known enough to make him write to Chris Wormald, the cabinet secretary, asking him to examine communications between Mandelson and Epstein.

Brown was told “no departmental record could be found”. Which is unsurprising, given Mandelson is said to have used his private internet account casually to forward secrets, while also expressing contempt for Brown’s prime ministership (“Finally got him to go today,” as one 2010 email to Epstein read).

Related articles:

As one senior Whitehall source told me last week, referring to Mandelson’s email records: “If he had been a mere civil servant, he would have had his fucking door kicked in by now.”

It is no wonder Brown told a friend around the same time last year: “Peter Mandelson is a very bad person.” At the time, this seemed an extraordinary thing to say about a man whom Brown rehabilitated in 2008 by elevating him to the upper house and into the cabinet, after Mandelson had already been sacked twice from the cabinet under Tony Blair.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

But in retrospect, Brown was always a very different character from Mandelson, who in 1994 sowed the seeds of an on-off, decades-long feud. After the death of the former Labour leader John Smith, Mandelson sent Brown a fax that Brown considered to be “duplicitous”. It set out the case for him standing aside for his junior partner Blair in the leadership struggle that ensued.

Mandelson had promoted Brown and Blair to the exclusion of others in the 1980s under the leadership of Neil Kinnock. Brown and Mandelson had an intellectual rapport back then.

But Brown has never shared the fascination with money that helps to define the Mandelson problem today. Brown paid his own way in Downing Street, left office in debt as a result and went on to decline his prime ministerial pension nonetheless. As a Scottish Labour ally from the 1970s Alistair Moffat tells me in my new biography of Brown, a son of the manse, he “is the least materialistic person I’ve ever met”.

Which is partly why Brown – who never accepted a single gift while in office – was so appalled by the 2024 scandal involving free gifts for Starmer, whose government he fears is surrounded by too many lobbyists.

Rupert Murdoch is perhaps the ultimate lobbyist, whose values diametrically oppose what a Labour government should stand for. His media outlets have hounded Brown since at least the year 2000.

In 2006, the Sun published details of Brown’s son’s cystic fibrosis. Yet to Brown’s dismay, Starmer appointed David Dinsmore, the editor of the Scottish Sun at that time, as permanent secretary for communications after the prime minister interviewed and approved him.

Which goes to the heart of the Starmer problem: a values vacuum. McSweeney has sought to out Reform, Reform UK with anti-immigration rhetoric. Some on the left wanted him out before the latest scandal.

Now he may serve as a lightning rod, buying Starmer a few more days in office with his own resignation, though the prime minister seems unable to function without him.

But either way, Starmer, who came late to the Labour movement, will soon be forced out. And Brown for one, who represents the relative decency of a seemingly lost age, will be hoping the coming events herald a rebirth of the party he has served for five decades.

James Macintyre is a staff writer at the Church Times. His book, Gordon Brown: Power with Purpose, will be published on 12 February by Bloomsbury (£25)

Photograph by Simon Dawson/Bloomberg via Getty Images