You want to know why, and in the first week of the trial I thought I had it. This is Daniel Graham being interviewed by the police in October 2023:

Graham: “I can be all right I think, get ready for bed and go to bed, and then all of a sudden like that, I’m fucking wide awake.”

Police officer: “Right.”

Graham: “And I can’t fucking cope, I’ll toss and turn and I’ve got to get up and go and do something, or it’s me dad or Lisa, so I phone him and it’s him saying obviously everything’s going down the pan. I don’t sleep. I don’t do fuck all. So sometimes I’ll go for a drive and that’s why I bought a campervan. Sometimes I get the campervan and just fuck off. It depends how I feel. Or I’ll go and see one of me pals or if me bird’s there I’ll sit with me bird. It won’t be a long trip, I just fuck off in the car.”

Officer: "So you wouldn't plan, you don't really have set plans?"

Graham: “I’ll be honest with you, I don’t plan anything, like. I wake up in the morning and the only thing that gets planned with me is when hitting jobs and, like, completing jobs, like I don’t have plans for fucking tomorrow never mind the day after.”

Officer: “Is that why you find it difficult to recall what you did that night?”

Graham: “Like, I couldn’t tell you what I did that night.”

Officer: “You wouldn’t have any record of what you’ve done written down or…”

Graham: “I couldn’t tell you two nights ago what I did type of thing, like. I’m not a person who lives by routine. I used to be routine, used to be, you go on the wagons all the time before all this carry on with me dad and then don’t know what, start fucking, I cannot see the point in fucking routine now there’s only me.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

A middle-aged man despairing for his future, unable to bend life to his will. You recognise your own, don’t you? But darker. Graham seemed to hate life, or at least the strictures of it. “I can be a c***,” he told police. Maybe Sycamore Gap was his way of tapping out, a PG shooting spree: fuck you and fuck your tree, I’m done.

Adam Carruthers was different. “The mind goes blank,” he said. He was blank, polite, meek. Outside the courtroom, between sessions, he waited among journalists as we discussed the case. He never got testy, even when one of us speculated about him getting a lengthy sentence within earshot. His friends, there to support him, were less docile. One day, one of them did an enormous fart. It seemed like fair comment.

Daniel Graham, left, and Adam Carruthers

In the dock he stared forwards, never turning to his former friend. In the witness box he was cornered by the prosecutor, unable to explain his contradictions, but was puzzled rather than defensive. “When I woke up in the morning and had a quick look on my phone and every other article was about the tree,” he said, “I couldn’t really understand why there was such a major outbreak. It was almost as if someone had been murdered.”

In 2011 I was at the same court – Newcastle Crown Court – for the trial of Raoul Moat’s accomplices, Qhuram Awan and Karl Ness, who were found guilty of attempting to murder a police officer. The Sycamore Gap trial had many of the same ingredients: two deluded men unable to foresee their lies fraying in court; tree surgery; an overspill of media interest; cell site evidence; the search for a weapon; the solemnity as we heard about what these men did.

The full weight of the state was being lowered on to these two men. You could feel that in court

The full weight of the state was being lowered on to these two men. You could feel that in court

We were shown footage of the first police officer arriving at the scene: “If you could just clear back a tad, just a touch, just out of this area, so we can gather as much evidence as we can,” he said. The tree was on the ground, already dead, rangers standing around sombrely. The prosecutor talked through photos of the fallen canopy, the stump, the wall, the cut to the tree: “You can see there, can’t you, just above the cut, that silver paint.”

Richard Wright, a KC who had previously worked on the Manchester Arena inquiry, was the prosecutor. Another barrister was working with him. Behind them, a detective inspector and the Crown Prosecution Service. The judge, Mrs Justice Lambert, was a high court judge. The full weight of the state was being lowered on to these two men. You could feel that weight in the courtroom. Fuck us and our tree? No, fuck you and your lives.

“We literally saw it out of the window,” said John Watson. “This very striking image of this solo tree sticking out of the wall.” In 1990 Watson was producing a film called Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves. Kevin Reynolds was the director. They were in England together scouting locations. They had already been to Alnwick, and now they were on the B6318, “the military road”, which runs parallel to Hadrian’s Wall in Northumberland.

“We went to the driver, hey hey hey, hold on,” he said. “I don’t remember if it was the director or me who first spotted it, but we both thought it was really striking. So we turned off down a lane and walked over and looked at it and just completely fell in love with it. We thought it a fabulous location and started to think, OK, what are we going to film there?”

They used it for a scene in which a boy evades the sheriff’s soldiers by climbing up Sycamore Gap tree. Bacon was hung from its branches to encourage the soldiers’ dogs to jump upwards. Robin Hood, played by Kevin Costner, saved the boy. The scene goes on for about 10 minutes; the tree looks iconic, a place you would want to visit.

“I’m a Somerset farmer’s country boy,” said Watson, “so I’m in love with the countryside and I love trees. I’m always attracted to images like that, solo trees.” When he visits England from California he always goes to a hill near South Cadbury in the county he grew up in, to see a tree there. “It’s kind of in my soul,” he said, “my happy place I guess.”

I asked how he felt when the tree he made famous was chopped down. “It’s sickening,” he said. “Within minutes of it becoming news I was getting barraged by people sharing news clippings with me and photographs and video recordings of people talking about it, and suddenly it was more famous after it died than when it was living.”

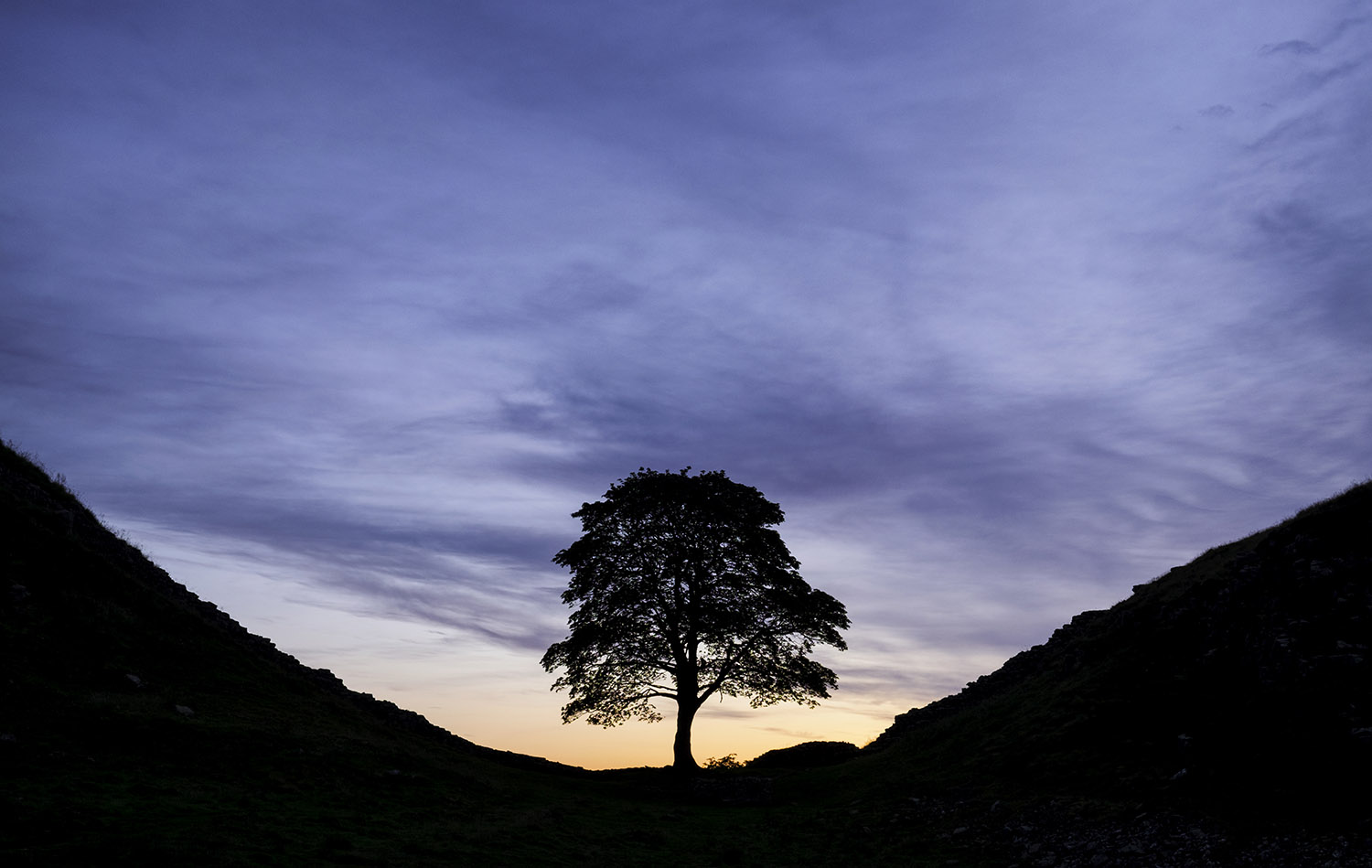

There were two big boosts to the fame of Sycamore Gap: being chopped down and being in the film. Before that, it wasn’t famous. It is believed to have been planted more than 100 years ago, but according to the National Trust, it was only in the 1980s that Lawrence Hewer, a warden, gave it a name. Jim Crow, an archaeology professor at the University of Edinburgh who directed excavations of Hadrian’s Wall at Sycamore Gap in 1983, remembers using that name then, but few beyond those specialists knew the name or tree back then.

By 1989, however, the Journal, a local paper, described it as “a famous Hadrian’s Wall landmark” in a story about Hewer planting a sapling there: “The spot between Steel Rigg and Housesteads Fort is named Sycamore Gap because of the sycamore tree that grows there. But the tree is dying and the National Trust, which owns land in the area, decided a replacement tree should be planted to make sure the name continues.”

According to the article, the National Trust said it would remove the established tree when it became dangerous and they hoped the sapling would “fill the gap”. It didn’t. “After the film, the tree acquired a celebrity, which is what all this is about – it’s celebrity, isn’t it? People started taking little bits from the sapling and the sapling died,” said Crow. I asked the National Trust if that was their recollection. They confirmed the sapling did not survive but could not recall why and said the established tree was healthy when felled.

The Sycamore Gap tree pictured the day after it fell on to Hadrian’s Wall

The film came up at the trial. While on the witness stand, Graham said he had never heard of the tree until 2021. He said he first heard of it when he was at Carruthers’s workshop and picked up a piece of string. Carruthers said he couldn’t use it, then laid it on the floor and said it was the circumference of Sycamore Gap, the “most famous tree in the world”. It didn’t quite ring true. The prosecutor doubted Graham’s claim to not know the tree until then.

Richard Wright KC: “Ever watched Robin Hood?”

Graham: “I’ve watched Robin Hood, yeah. Doesn’t mean I know where that tree is.”

Wright: “Living 40 minutes away, nobody in that area ever mentioned this legendary tree?”

Graham: “No. The first time this legendary tree was mentioned was in 2021, which I didn’t really have an interest in it. I cut trees down, I don’t collect them.”

Graham’s barrister, Christopher Knox: “The Land Rover, the Defender, who did that belong to?”

Graham: “My dad.”

Knox: “How long have you had it?”

Graham: “Since 2021.”

Knox: “You’ve told the police about how it came to be done up. Can you tell us?”

Graham: “When my dad had it, it went for an MOT and it was rotten underneath. It needed a lot of work done. It was my dad’s pride and joy, so I’d seen Adam Carruthers and asked him if he would rebuild the Land Rover for us, for my dad. He agreed. I sent the Defender to him and he had it for about eight month.”

Knox: “Was there a lot of work to be done?”

Graham: “Yeah it needed a full chassis.”

Knox: “Did he do a good job?”

Graham: “Yep.”

Knox: “And was it returned to your dad?”

Graham: “No.”

Knox: “Why not?”

Graham: “My dad hung himself.”

A drive through rural Cumbria. It’s somewhere good, somewhere you would like to live your life if you could just get it together, find your way to success somehow. The hikers in their expensive boots, the hills, the green fields filled with sheep, big beautiful houses, the kind coveted by city-dwellers on Rightmove. Carruthers existed in the pockets between all that, places you would never spot if you weren’t looking for them.

The plot of land where Graham lived, near Carlisle

He told the court he was “interested in spanners” as a kid so became an apprentice engineer at a local factory, but they didn’t keep him on. He became a caretaker for flats and a mechanic with a workshop in Kirkbride, down a narrow track, a place Graham called “the farm”. He lived in a caravan at the old fuel depot at an airfield with his partner and two children. It is as it sounds: a caravan at the old fuel depot at an airfield.

Daniel Graham was more visible. He lived about 20 minutes from Kirkbride near a village called Kirkandrews-on-Eden. He bought a plot of land there in 2015. It’s peaceful, birds chirping, cows in a neighbouring field, trees giving shade to his caravan. There’s a barn on the site, a green shipping container, and what looks like a huge grave with a cross, horse statues and a stone bench on top of it. I think it was for his horse.

The plot is protected by two big ornate gates with the letters “DMG” on them. A sign on one gate says: “Private Keep Out.” On the other: “Beware of the dog.” The gates are chained up, bollards raised behind them. Graham has built banks using earth to give the plot some privacy from the road. There’s a postbox at the front gates and a doorbell which seems to have a camera. A few of his 11 vehicles are visible: a flatbed lorry, another lorry.

He used to work for other people, then drove lorries, but found it “the most boring job I’ve ever done in my life”. He started a groundworks business, at the weekends at first, then full-time: house foundations, patios, fencing, trees. That’s what the vehicles are for, and Carruthers fixed them for him. In 2021, Graham asked Carruthers to fix his dad’s Land Rover, but before it was finished, Graham’s dad killed himself.

The local coroner signed a “record of inquest” for Mike Graham in November 2021: “On 6th June 2021 Mr Graham delivered a letter to his employer indicating that he intended to retire. He spent the morning with family before they left at approximately 13.00. At approximately 15.45 his mother returned to his address and found his body. Mr Graham had hanged himself using a rope suspended from a beam in his loft.”

(Last week the Sun reported that Graham had an argument with his gran at his dad’s funeral. The story quoted a family friend: “They had this weird disagreement over who had found Michael. They both claimed to have been the one to do so.” I went to the house I think Graham’s gran lives at. A sign said: “No cold callers.” Nobody answered the door. A few minutes later a woman appeared at the window mouthing “no”, so I drove away.)

Graham asked Carruthers to finish the Land Rover in time for his dad’s funeral. Carruthers got it done, working through the night with some pals. Graham appreciated that, considered it a good turn. They became closer. “I started going up to Kirkbride of a night-time more often, spending more time there,” Graham said at the trial. “And that’s when the friendship kind of grew, because of what he’d done with my dad’s truck.”

'They shared takeaways, helped each other with tasks, spoke “most days”, according to Graham'

Several nights a week, Graham went to “the farm”. They shared takeaways, helped each other with tasks, spoke “most days”, according to Graham. Carruthers said they’d phone each other “to see how the day’s gone”. “Best pals”, was Graham’s phrase. Wright called them “obsessively close”, which seemed unfair, but it was odd after Graham had said he is “not a people person”, a description that seemed like an understatement.

Graham: “I’m quite antisocial. I don’t go, since this happened to my dad like, I’ve got a very, very small circle of friends, people I entertain more, entertain nobody now like. Like I say, it’s either my bird or Adam. That’s about it.”

Officer: “Does Adam stay over at your place?”

Graham: “Does he fuck.”

Officer: “No?”

Graham: “Are you trying to say we’re poofters or something like?”

Officer: “No, I’m just asking if as a friend he may stay?”

Graham: “No, fucking definitely not.”

Officer: “Do you ever stay at his?”

Graham: “No.”

(This week the BBC reported that Carruthers and Graham were suspects in an investigation into alleged homophobic assaults. One alleged victim was in a layby, just nine days before the tree was cut down, when he claims icing sugar was thrown at him and alleged homophobic abuse shouted. Similar alleged assaults against others had been recorded on a phone. Two men were arrested but the CPS did not prosecute.)

After the tree was felled, Graham and Carruthers remained close, but then came the arrests. After Graham’s first arrest, in October 2023, Carruthers couldn’t get hold of him and left messages. Weeks later, Graham showed the police photos of Carruthers with chainsaws. In 2024, Graham made an anonymous call to the police: “One of the lads that done it, Adam Carruthers, has got the saws back in his possession.” The police searched, but never found the chainsaw used to fell the Sycamore Gap tree.

Their friendship was over. “The last time I spoke to Adam was when I took him a milkshake up to the farm at the night and told him what the situation was and that we were no longer friends while all this was the way it was,” Graham said. “I’ll be going my way and he can go his way. That was the last time I spoke to Adam.” In court they never looked at each other.

I was making French toast at home on 24 September 2023 when my dad’s wife called: come quickly, your dad’s not well. I switched the hob off and drove. She’d said to go to the house, not the hospital, so I knew what to expect when I got there. He was on the ground, already dead, paramedics standing around. I asked if I could hug him. They said yes. I put my head to his chest, then they put him to bed.

For the rest of the day I waited in the front room with his wife, took his dog for a walk – “Is your dad OK?” asked a neighbour in the park; “No, he’s dead” – and went upstairs a couple of times, once to identify him for the police and once to look. He shrivelled in those hours, his face becoming a strange face that kept sneaking into my thoughts over the next few months. For a while, every old man I saw seemed to be him.

It felt like irretrievable loss. It was a tree, but one on which we hung meaning

It felt like irretrievable loss. It was a tree, but one on which we hung meaning

So I was in a funny frame of mind when the tree was chopped down four days later. It felt, daftly, like more grief. Graham and Carruthers felt no grief. In their messages they seemed entertained. “It’s gone viral. It is worldwide. It will be on ITV News tonight,” said Graham in a voice note. In the witness box, Carruthers kept repeating how surprised he was by the reaction over “something so small”: “My understanding was it was just a tree.”

I get it. As Graham said, he and Carruthers were paid to fell trees, mostly those suffering from ash dieback: “Once one gets it, if there’s a line of ash they’ll all get it,” Graham said. They were skilled at it, people paid them to do it, and nobody mourned the trees they cut down. Trees are felled all the time. My own council removed 1,450 over the last year. If you regularly cut them down, one more probably doesn’t seem a big deal. But it was.

“I was surprised at the international, global outcry,” said Crow. “It just shows you the reach of these images now. I was in a conference in Athens about three weeks later and when I mentioned it, people went, oh, the tree. The celebrity was in its demise, in its martyrdom.”

He was being slightly flippant I think. I asked whether he was devastated when it was cut down but he focused again on the reaction: “I wasn’t devastated. I was disappointed and I thought, why should somebody do that? And I wasn’t even that worried about the damage to the wall. I thought it was pretty minor. I was astonished by the response really.”

Charlotte Crowe, a pupil from Northumberland, presents Judi Dench with one of the tree’s 49 seedlings

Crow has done a lot of research on Sycamore Gap, some of which appeared in an anthology, Hadrian’s Wall in Our Time, which was published last year. His contribution was measured, as is the foreword, written by Rory Stewart. However, this is the book’s epigraph: “To the memory of a fallen tree in Sycamore Gap.” And this is from the introduction: “We hope that this will provide some comfort to those grieving for the lost tree.”

Oh dear. The People’s Tree. A maple in the wind. In hindsight, we may have lost the plot. Other responses to the tree being felled included poems, art commissions and the National Trust’s Tree of Hope scheme, distributing 49 saplings from its seed; the immortal life of Sycamore Gap. Part of the tree will soon be at the local visitor centre, lying in state. Its image lives on, in north-east gift shops; the illustrated icon; an Etsy martyr.

I’m not immune. I grew up in Northumberland, eight miles from Newcastle. I have no memory of ever visiting Sycamore Gap as a child. Maybe I walked past it, but when we went to the wall it was to visit the big forts, Housesteads or Vindolanda. The tree was never mentioned. My first memory of it was watching Robin Hood at the Metrocentre with my mum, then buying the Bryan Adams single in Our Price.

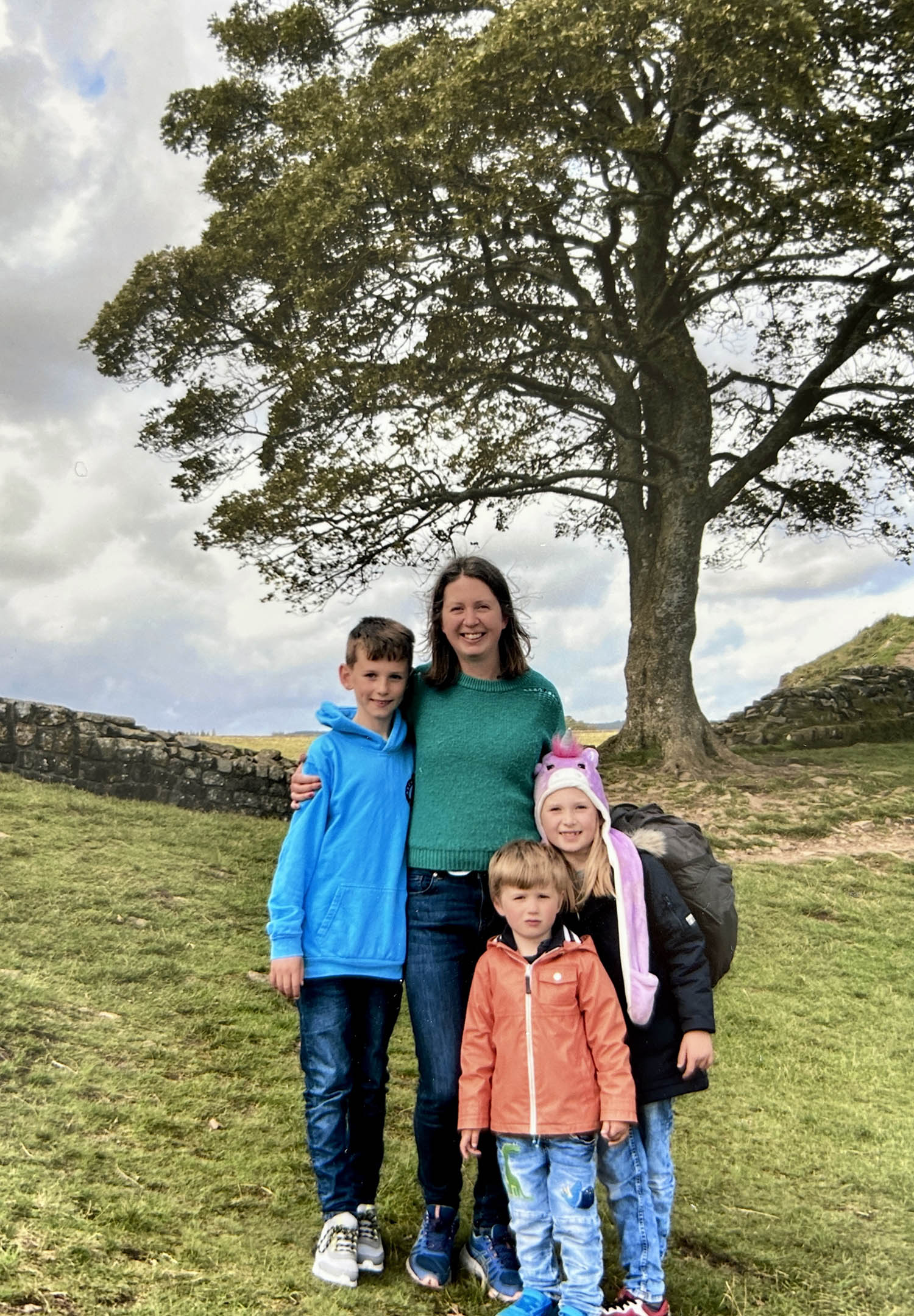

After that, a connection developed somehow, because in 2009, when my girlfriend and I walked the length of Hadrian’s Wall on holiday, we paused at Sycamore Gap. I waited for some other hikers to shove off, then got down on my knee and asked her to marry me. She said yes. We had kids, who we took to the tree many times. When friends came to visit, we took them and their kids. It gathered meaning.

Writer Andrew Hankinson’s family at the Sycamore Gap tree, where he proposed to his wife

Embarrassingly, we now have four pictures of Sycamore Gap on our walls: an illustration; a photo my wife’s dad took; a photo of our family in front of it; and one my dad gave us as a wedding present, which isn’t a great photo, but he couldn’t walk very well so I appreciated the effort it took to reach the tree. When people say it’s just a tree, I think they don’t know how intertwined it became with so many lives.

That sentiment leaked worldwide via the internet and became diluted, uniform, but for those of us who regularly went there, it felt like irretrievable loss. It was a tree, but one on which we hung meaning. People left ashes there. People took children there. It was a totem for the lives we were living, often carefully constructed, and then it was gone. Maybe Carruthers and Graham didn’t understand that. Maybe they did.

It was the perfect plan, except for the many, many ways they shit the bed. On the night the tree was felled, between 11pm and 2am, Graham’s black Range Rover – an 09 reg; “the black pig” he called it – was recorded by automatic number plate recognition cameras travelling from Carlisle towards Sycamore Gap then back again. Graham said he often left the keys in the ignition or visor, so someone must have taken it.

Carruthers’s iPhone, which he lost after the tree was felled, wasn’t connected to the network. His 2G Samsung didn’t reveal his location. Graham’s iPhone was on the network travelling towards Sycamore Gap, but disconnected 10.5 miles from the tree, then reconnected just under two hours later, travelling away from Sycamore Gap. He said he left his phone in the car, so whoever had his car had it. The prosecutor pushed him.

A screengrab of a video recovered from Graham’s phone showing the moment the tree was felled

He pushed back: “Listen, you might be a little bit more educated than me and you’re trying to make a fool of us on this stand,” Graham said. “I’ve told you what I’ve told you about my phone. I’m not trying to make a story up. I’m not trying to cover my own arse. I’m trying to get it sorted so I don’t get the blame for something I haven’t done.”

The police found a video on Graham’s phone of a person felling a tree. It was filmed at Sycamore Gap at 12.32am on 28 September 2023. At 1.30am that night, Carruthers’s partner sent him a video of their child. Carruthers replied: “I’ve got a better video than that.” At 1.39am the tree video was sent from Graham’s phone to Carruthers’s phone. There was also a photo on Graham’s phone, taken shortly afterwards in his yard, of a chainsaw and a wedge from a tree in the boot of his car. Neither was ever found.

In the morning, Carruthers and Graham exchanged their messages, including about a Facebook post by Kevin Hartness saying whoever did it was “weak”. “Weak? Fucking weak? Does he realise how heavy shit is?” said Graham. “I’d like to see Kevin Hartness launch an operation like we did last night,” replied Carruthers. In court, Carruthers said he was saying “he” not “we” (meaning whoever did it). It was played back. He said he meant to say “he” not “we”.

We don’t know the motive. The prosecution said Carruthers had a thing for the tree and it was a trophy. I ran that over in my head: a chainsaw enthusiast proving himself against the famous tree. I wasn’t convinced. For Graham, I thought at first maybe he did it because he was so angry; he wanted to mock our idol, reduce it to the sad stump it is now, surrounded by a fence erasing any hint of wilderness. But I don’t think we have the answer yet.

A few speculated about a planning grudge. In 2016, Graham applied to build stables on his land: “The development is for the keeping of horses for hobby and pleasure use,” the application said. An objection said: “They are digging up green fields to put sheds, portacabins and other buildings. Then applying for a house.” But the stables were approved. Graham’s application also mentioned a caravan which he said was a “tea/bait room and also for the safe storage of medicines for the horses and a first aid kit”.

Graham moved into the caravan. In 2022, he applied to retain it as his lawful residence. In his application, he said he had been living there since 2016, seemingly thinking a four-year rule meant he could no longer be evicted. The council’s decision came down to whether the caravan was still a caravan. Graham argued not, because it was attached to the ground. The council said it was. His application was rejected in April 2023.

Supt Kevin Waring outside court after Graham and Carruthers were found guilty of criminal damage

An enforcement notice was served in September 2024, a year later. He appealed to the Planning Inspectorate, but lost in April this year. Hadrian’s Wall was not a factor and the tree was in a different county, miles away. Graham’s land is in the Hadrian’s Wall “buffer zone”, but when he applied to build a new store and shed last year, Historic England did not object, nor did the council’s historic environment officer. Beaumont parish council objected, saying “residents and planning officials have felt threatened” by Graham’s “dominant and oppressive behaviour”, but Cumberland council approved it.

Whatever the motive, Graham was found guilty of damaging the wall and tree. He has been in custody since December “for his own protection” after what his barrister described as “an episode”. He’s being protected from himself. Carruthers is in custody now too. After the verdict, he puffed out his cheeks and raised his eyebrows. A first reaction. It dawned on me that he had been trying hard to stay calm and not come undone.

The value of the tree is yet to be agreed. On the day of the verdict, Knox said it was about £450,000, but the figure was still in dispute. Regardless, all the barristers agreed that the sum will almost certainly fall into the highest category of “harm”. The judge will sentence them on 15 July, her remarks likely televised. On the day of the verdict she warned her powers “include a significant period of custody”. The maximum sentence is 10 years.

Outside the court, the show continued: statements, cameras, a job well done. I stood watching from across the road, listening to three people sitting at a table discussing the verdict. “It’s an iconic tree. Very, very, very rare. That’s like blowing up the Tyne Bridge,” said Eddie, who told me he’s homeless. I asked what he thought the sentences should be. He thought they should get life. His friend agreed. “A life for a life,” said Eddie.

When another writer at the trial heard I’d proposed to my wife at the tree, she said I was exactly the person the prosecution is invoking. That made me uncomfortable: were the two men facing long prison sentences because people like me attached such meaning to a tree? I wanted them punished when I was in that funny frame of mind, but after hearing about the caravans, suicide, children, the lives the men were living, I felt differently: if the value we put on the tree determines whether they stay in prison, it’s worth nothing at all to me.

Photographs by Simon Bradfield/Getty, Northumbria Police via AP, Dan Kitwood/Getty, Owen Humphreys/PA, Glen Minikin/the Sun, CPS/PA, Ian Forsyth/Getty