When he was a child, Paul Nurse walked through a park to school on his own every day. “It was over a mile, which is quite a long way when you’re six or seven,” he says. “I was rather solitary. I used to talk to myself and take note of everything going on around me – the birds, the trees, the squirrels, the foxes, the season changes – and wonder about them. I began to notice strange things about plants. I saw that the leaves grew bigger in the shade, for example. And then I would read up and find that the leaves were catching more sunlight.”

He started mapping cobwebs to work out where the spiders positioned them to catch the most flies. “In the evening, of course, you’d see the stars coming out and I could see there were some bright ‘stars’. I discovered they were planets, moving around. So even from quite an early age, I got this interest in natural history and astronomy. And that really was my introduction to science, because I didn’t come from an academic family.”

Nurse, 76, went on to win a Nobel prize for his work on cells. The geneticist helped found the Francis Crick Institute, the biggest biomedical laboratory in Europe, and last month became president of the Royal Society, Britain’s most prestigious scientific institution, and the first person since the 18th century to be elected to the position twice. But it all began with those walks across One Tree park in Wembley, north-west London.

“Curiosity has always driven me. I’m a discovery scientist. I don’t really do anything very useful,” he says modestly, but his research into the cell cycle of yeast helped to explain how tumours spread and led to new cancer drugs.

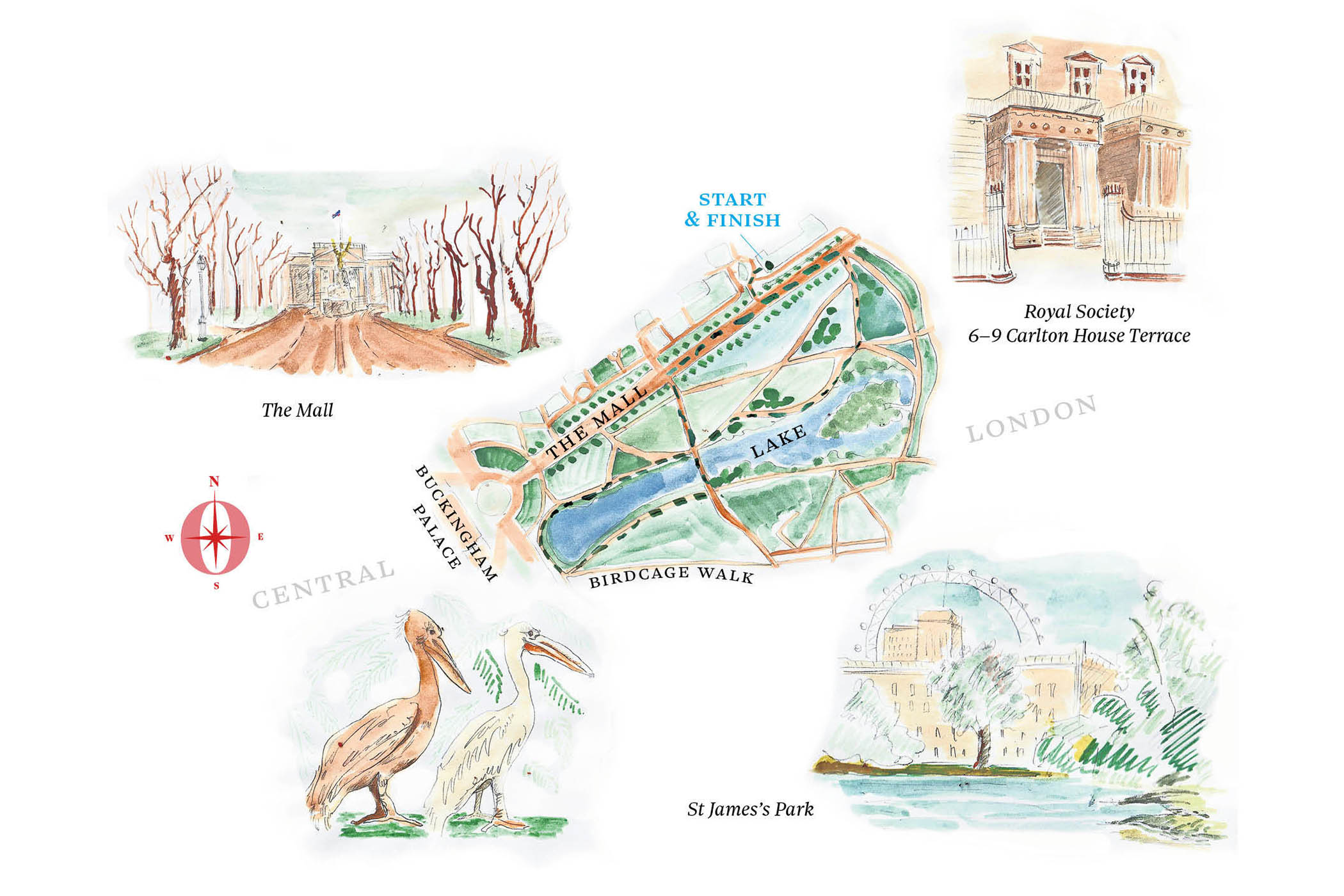

Nurse has “always loved parks”, and our walk will take us through two of London’s finest – St James’s Park and Green Park – but we meet in the white stucco grandeur of the Royal Society’s headquarters on Carlton House Terrace. Imposing portraits of Isaac Newton and Charles Darwin hang in his office. Albert Einstein is on a landing wall.

“It is a little bit intimidating,” Nurse admits. The president has a swanky grace-and-favour apartment with a huge balcony looking out towards the Houses of Parliament – “much bigger than my tiny flat in Clerkenwell”, he says.

We head down the steps to the Mall, where the black cabs purr towards Trafalgar Square, and enter St James’s Park. Nurse says it “couldn’t be more different” from the park he walked across as a boy.

“It’s totally manicured, surrounded by all these buildings of state – you’ve got Downing Street just over there. One Tree park was a standard recreational park, very simple.”

But there are still similarities, he says: “It’s a little bit of country in the middle of town.”

He points to the trunks of the giant planes that line the walkway – “look at these trees, it’s amazing really, it’s wonderful to see”.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

We turn left past the immaculate flower beds, and take the path around the lake. There are pelicans on an island and the quacking ducks are not entirely drowned out by the men in green uniforms blowing away fallen leaves. Having lived at the Royal Society for five years during his first term as president between 2010 and 2015, Nurse knows every twist and turn of these tracks.

“I used to go jogging every morning all around here,” he says. “It was quite often dark and I remember once I caught up with a small group of three men who were jogging quite slowly in front of me. I had a chat and then I realised it was David Cameron, who was prime minister at the time, with his bodyguards.”

He knows Keir Starmer well because the Crick Institute is in the prime minister’s constituency of Holborn and St Pancras. Nurse was among a group of top scientists who recently wrote to Starmer to express their concern about the timidity of the government’s curriculum and assessment review. He has still not received a reply.

“I feel quite strongly about this,” he says as we walk past a group of pre-schoolers in hi-vis jackets out for some fresh air. “I think our education system specialises too early. There is a separation of school kids into different categories. Those who go in a scientific direction lose contact with the humanities, and the more human side lose contact with understanding the natural world. That is unfortunate.”

At the Crick, he created a teaching laboratory for local primary schools. He says: “At that age children are very interested in the world.”

But he worries that pupils’ innate inquisitiveness is drummed out by a system that focuses on a narrow set of academic results, saying: “I don’t know if there are too many exams, but what I do know is that we have to encourage curiosity and a love of knowledge. You’ve got to understand processes and you don’t get that just by learning the periodic table.”

He still remembers waiting up late to see the Soviet Sputnik 2 space ship, carrying Laika the dog, shoot across the sky in the 1950s. He says: “I was about eight. This bright star came over the horizon and I ran down the street in my pyjamas chasing it.”

When he was 11, his parents bought him a telescope. Nurse says: “It was a very simple one but it was just enough to see the moons of Jupiter, the rings of Saturn, the mountains on the moon. Something about being directly connected to the stars you can see up there gives a sense of huge wonder.”

I opened up the birth certificate ... my mother was not my mother

I opened up the birth certificate ... my mother was not my mother

Paul Nurse

We walk past Buckingham Palace and cross over into Green Park, through the ornate, golden Canada Gate, a symbol of Britain’s historic connection to the rest of the world. Nurse worries that the UK is turning in on itself and the government’s approach to immigration risks harming scientific research. He says: “Science is a worldwide endeavour. I get letters from people saying, ‘We don’t need to have anybody from overseas, we can do it all ourselves.’ That’s total nonsense, it would be like the Premier League saying, ‘we’re only going to have British football players’. We want the best scientists in the world.”

Researchers still want to come to this country “because Britain has a reputation for being one of the highest quality science bases in the world”, he says, but the cost of visas and NHS fees means the UK is losing out to other countries: “These are the most highly talented people in the world and yet we’re putting barriers in the way of getting them.”

There is, he points out, an opportunity to snap up some of the best scientists from America who feel alienated by Donald Trump.

“Science depends on truth, evidence – courteous, rational debate. All of that is missing from the present US administration,” Nurse says. “They’ve got used to the idea that they don’t have to worry about evidence. They just make a statement. If they don’t like climate change ideologically, they just say it’s hooey. We see the Reform party doing the same thing. We’ve got vaccines, which are one of the great saver of lives, being challenged.”

Nurse, who has lots of good contacts across the Atlantic, says: “Scientists there are scared. There’s a National Academy of Sciences in the US, which is equivalent to the Royal Society here in the UK. It’s funded by government and they’re petrified government will take the money away – and of course the government threatens to do so. It’s an attack on science but it’s actually an attack on the democratic process. There is a wholesale attack on intellectualism. They’re fining universities because they don’t like what they say. This is an erosion of civilisation.”

We turn the corner at the top of the park near Piccadilly and head back down towards the Mall. It was when Nurse went to be president of Rockefeller University in New York in 2003 that he made an extraordinary discovery about his own family. He had applied for a green card, and says: “To my surprise I was rejected. By then I had a Nobel prize, I was knighted, I was president of the richest university per capita in the United States. And they said no because they didn’t like my birth certificate.”

His birth certificate was the short version, which confirmed where he was born and that he was a British citizen, but did not name his parents. To satisfy the American authorities he applied for a full birth certificate from the Register Office in London.

“I opened it up and there [it said] my mother was not my mother, it was my ‘sister’. And the father was a line. I was completely astonished.”

At first he thought there must have been a mistake. He says: “I couldn’t quite believe it, but as soon as I believed it, I calculated that my mother was 17 when she got pregnant. The family did their best to protect her. They sent her to her aunt in Norwich. She gave birth there and then my grandmother came up and pretended to be the mother.”

His mother, in turn, pretended to be his sister. A couple of years after he was born, she got married.

“There’s a very poignant picture of my mother’s wedding where she’s holding her husband’s hand and my hand,” he says. She went on to have three other children and he discovered later that she had always kept a photograph of him alongside theirs on her bedside table. He recalls: “One of my ‘nieces’, now my half sister, said, ‘Why do you have Paul there?’ And she said, ‘Well he was like my baby brother’. The truth was kept a secret.”

For years, Nurse tried to trace his father, but all the family members who might have had clues to point him in the right direction were dead. He did a commercial DNA test in the hope that an ancestry website might help to find him. There were a couple of potential matches so he tried to make contact but nobody replied.

“I’m British, I thought, well, perhaps they don’t want to know. It’s a complicated thing,” he says. Then two years ago he appeared on a BBC programme with Turi King, the genealogist and geneticist who had worked on establishing the DNA of Richard III. She offered to try to track his father down. A few days later, while he was in Japan at a conference, he got an email saying she had succeeded.

Nurse discovered that his father was a local man who had been posted to Egypt in 1948 on national service. He says: “He lived very close to where we were brought up, only 200 metres away. He came back and made my mother pregnant during leave for a couple of weeks. I don’t think he had any idea that I existed.”

When he returned to the UK, he married and had another family. Nurse says: “He became a London bus driver. Weirdly he worked out of the Alperton bus station where I used to collect bus numbers. Also weirdly, I was at primary school with my half sister [his daughter].”

Nurse does not want to name his father, to protect the privacy of his newly discovered relatives.

“He died about five years ago so I never met him but I have six half siblings on his side. I’m going to the birthday party of one of them next month,” he says, adding they were “completely shocked” to discover he existed.

“To have me suddenly parachuted into their midst was a bit odd, but it’s all been fine,” he says. His own emotions were less complicated.

“Catharsis is too strong, completion is appropriate,” he says. “I never thought I would find out. I’m very phlegmatic really. It’s how it was. There was no tragedy for me. I was brought up normally. There isn’t anything for me to feel agitated about.”

By now we are at the end point of our walk, the cafe in the middle of St James’s Park, but we are still talking. I ask Nurse whether he thinks he may subconsciously have been attracted to the field of genetics because of his own unusual background.

“It’s ironic, but I think it is an accident,” he replies. And yet he says he always felt “different” growing up in a house with no books, and his story is in a way the ultimate test of the balance between nature and nurture. He can see something of himself in photos of his father.

“It’s less the looks and more the mannerisms,” he says. “I have a picture of him when he was in his 80s. He was leaning on his fist on the table, which is something I do. He had a glass of red wine in front of him, which is something else I do.”

He was not an intellectual but Nurse thinks it may be that he simply never had the chance to do that. He says: “He had a reputation for being quite curious. I honestly think he didn’t have the opportunity. There was a big shift that occurred after the second world war and suddenly the door was opened. Before that hardly anybody would have gone to university from a working-class family. It’s back to education. I think my father was just born a little too early.”

Photographs by Tom Pilston for The Observer

Illustrations by Ellie Wintour