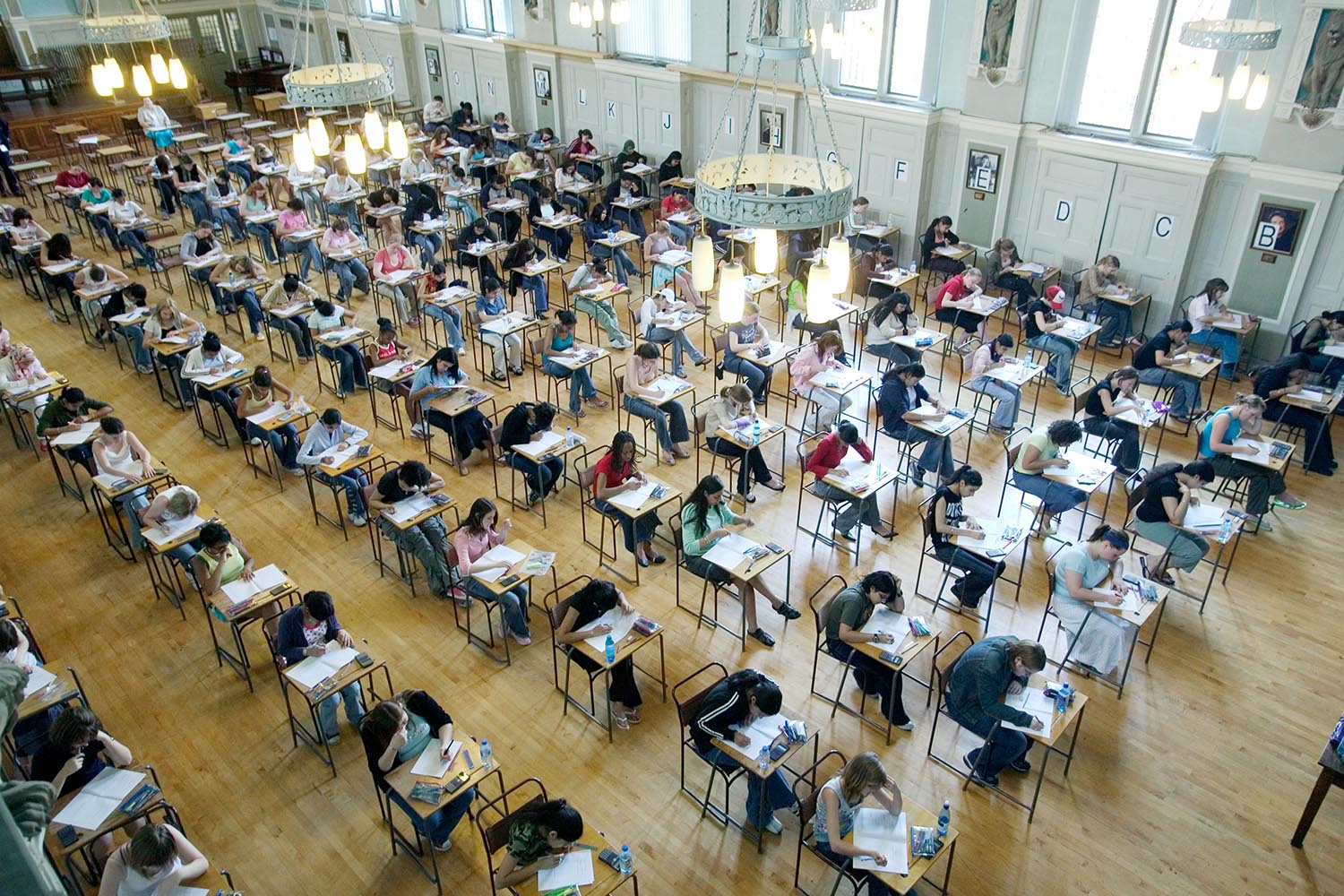

As pupils prepare to get their A-level and GCSE results this month, an education revolution is under way that could make the traditional exam – sat by pupils together in a hall on a single day – a thing of the past.

Teenagers would instead take personalised papers, working through different levels in their own time, under proposals for “adaptive assessment” made possible by artificial intelligence.

Mary Curnock Cook, chair of Pearson, which owns the Edexcel exam board, said: “You could potentially get rid of the idea that everybody does their maths GCSE on 23 May at nine o’clock in the morning, which I think is daft. Why do we expect all children born at any time within a 12-month window to be ready for their exam on that precise day? You should be able to let people take their assessment when they’re ready for it.”

Exam boards are already trialling AI examiners, using machines to “double mark” papers alongside a human assessor. Some tests, including IGCSEs, are delivered digitally.

“But the real prize is to have adaptive testing, which would completely change the face of how we assess and how students engage,” said Curnock Cook, former chief executive of Ucas, the Universities and Colleges Admissions Service. “If you get a question wrong, the next question it serves up will be easier. The nirvana is a massive national test bank of assessment questions that you take when you’re ready at any time.

“Some subjects, such as languages and maths, could be done like piano exams. You do grade 1 when you’re ready for grade 1, and grade 2 when you’re ready for grade 2. You build up competence and knowledge, and work through the levels. Teaching would be by stage, not age.”

She stresses that any reform would need to be introduced carefully, but the concept is gaining support. Charles Clarke, the former Labour education secretary, believes a more flexible system would better capture the different abilities of every child.

“In some subjects, AI can help develop achievement-based assessment systems which better reflect students’ own individual competence and capacities. That is the direction in which assessment should be going.”

Related articles:

At the moment, about a third of pupils, in effect, fail their GCSEs because they do not get a grade 4 or above in English and maths.

The education system is already being transformed by AI. More than half of teachers say they have used it in their work and at least 90% of university students rely on AI tools, including ChatGPT.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Ministers hope the technology can reduce teacher workload and help with a retention and recruitment crisis. The Oak National Academy’s AI lesson-planning assistant, Aila, launched last year, is saving users an average of about three hours a week.

The Department for Education is now funding the development of a tool that scans and marks handwritten homework. Another pilot programme allows nursery staff to speak into a bodycam to make observations about the children in their care over the course of the day. The system then summarises their comments and produces a report.

The government also wants to harness technology to drive school improvement. Last week, the latest attendance figures showed a reduction in the number of persistently absent pupils. Officials say this success was partly the result of a new AI tool that allows headteachers to spot patterns and compare their school with other institutions in similar circumstances.

‘The genie’s out of the bottle... there’s a danger of the education system being left behind’

‘The genie’s out of the bottle... there’s a danger of the education system being left behind’

Tom Nixon, Faculty AI

One multi-academy trust found that there was a lower attendance rate at one of its schools on Tuesdays than other days of the week. It turned out that the school bus was often late on a Tuesday because of roadworks, so the trust bought two minibuses to help with morning pickups and got more children to school. The government is planning to roll out similar AI data-matching systems on everything from literacy rates to teacher retention.

The tech company Faculty AI has been given a contract to create the “AI education content store”, which uses the national curriculum and anonymised teacher and pupil work to create a pool of trusted data for developers to use to train AI products for the classroom. So far, more than 20,000 items of content have been brought into the system, with trials showing it can increase accuracy of AI marking from 67% to 92%.

Tom Nixon, Faculty AI’s managing director of applied AI, said: “The genie’s out of the bottle – young people are using AI. If the education system doesn’t embrace it, there’s a danger of being left behind.”

Critics warn of a rise in cheating and the collapse of young people’s attention spans.

The historian Niall Ferguson has claimed that AI is having a “catastrophic effect” on human intelligence, while Katharine Birbalsingh, known as Britain’s “strictest headteacher”, said earlier this year that AI would harm educational outcomes, particularly for disadvantaged children. “Being on a screen actually dumbs you down,” she said at a conference run by the Alliance for Responsible Citizenship, a thinktank associated with the rightwing Canadian commentator Jordan Peterson.

But others insist that AI can improve outcomes by creating tailored lessons that simultaneously stretch the brightest pupils while preventing those who struggle from falling behind. Geoff Barton, former head of the Association of School and College Leaders, said: “Of course there will be risks around it, but I think we ought to embrace some of the possibilities. You can have a personalised tutor who is able to give a high-quality assessment of what a young person has done and feed back on what they might need to do next. This is potentially very democratising.”

Jim Knight, the Labour peer and former schools minister, argues that in the age of AI, education needs to be rebalanced to encourage “critical thinking and curiosity” as well as knowledge and memory to prepare people for the jobs of the future.

“I do worry at times that the government’s drunk too much Silicon Valley Kool-Aid, and we’ve got to be careful of that, but there are huge numbers of disengaged kids and huge numbers of teachers leaving the profession,” said Lord Knight. “This technology is capable of helping us with the problems that we’ve got, as well as creating opportunities to do things that are currently inconceivable.”

Steve Rotheram, mayor of the Liverpool city region, has struck a deal with the educational tech firm Century to introduce its AI teaching platform into schools as part of efforts to reduce inequality. The system identifies a pupil’s areas of strength and weakness, then creates questions specific to each child.

In a pilot last year, 4,000 students showed an average improvement of 10% in their scores. Teachers each saved more than nine hours on marking and lesson planning over the three-month period. Headteachers found particular benefits for children with special educational needs.

According to Alex Russell, chief executive of Bourne Education Trust, children at his schools are encouraged to use AI for help with research and creative writing. “We’ve had a lot of success with younger boys who are reluctant to write because they don’t find the topic interesting. They can put words into AI to create a picture of what they’re trying to write about, then they can use that visual stimulus for their creative writing,” he said. “The world is changing and education has got to change with it.”

At Westminster academy in west London, staff use AI to prompt debate in class. Associate assistant vice-principal Anita Shakya, an English teacher, said: “It’s a good way of expanding on your ideas.”

Parents and employers want the education system to do more to give children the skills they need for work. An Opinium poll for The Observer found that 66% of voters think schools should teach pupils how to use emerging technologies such as AI but only 41% think they are doing so.

A recent survey of 300 businesses by PricewaterhouseCoopers found that only four in 10 believe the current curriculum and assessment system prepares young people properly for the workplace.

Experts warn of a growing digital divide. Private schools are three times more likely than state schools to have a clear strategy on using AI, while more than a third of parents of school-aged children report that their children do not have continuous access to a device at home on which they can do their school work.

The government, they said, also needs to do more to ensure all pupils have a computer or tablet and reliable broadband.

Photograph by Andrew Fox/Alamy