Hours after several peers rejected accusations that they were deliberately delaying the vote on the assisted dying bill, Thérèse Coffey stood up in the House of Lords to introduce its 66th amendment.

The former health secretary has tabled 95 out of 1,227 amendments; a number unprecedented for many years, and so extensive that the bill’s supporters believe they will run out of time to get it through.

The Lords has 14 Friday sittings to discuss assisted dying; last week was the eighth. The house began the day still debating amendments to the first clause of the bill – there are 58 more clauses to go.

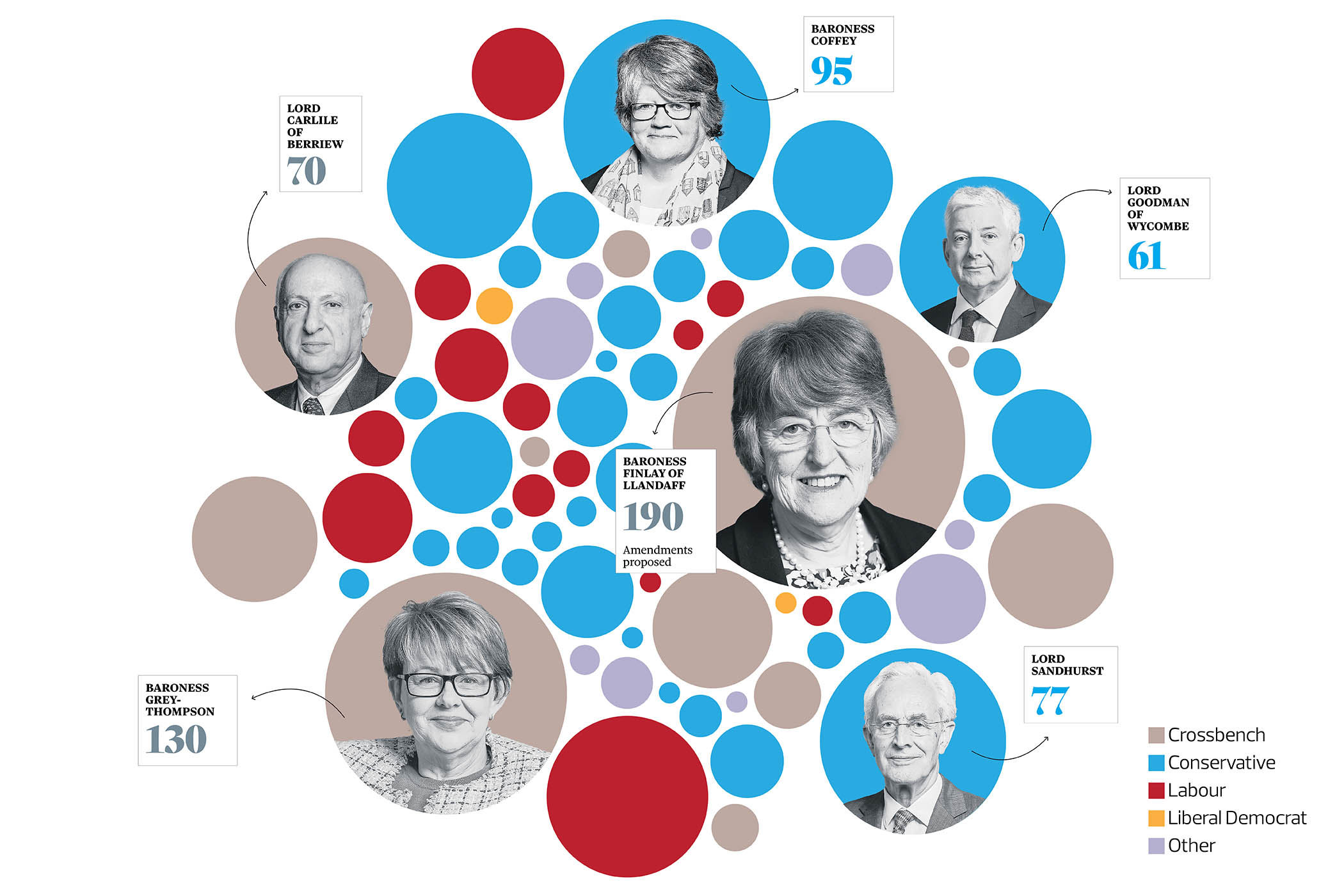

Coffey is not the most prolific amender. Ilora Finlay, a professor of palliative medicine and former president of the Royal Society of Medicine, has tabled 190 – more than twice as many as the crossbencher had brought since she was made a life peer in 2001, analysis by The Observer shows.

Figures such as Finlay are part of the rationale for having an unelected upper chamber, responsible for revising legislation to remove loopholes and inconsistencies. The Lords considers itself to be the obverse of student politicking, proud of its seriousness and range of expertise.

Coffey cleared her throat. “Recognising how artificial intelligence is emerging, I thought I’d put down quite a blunt amendment to at least allow us to have a debate,” she said. Coffey was asking her colleagues to ensure the terminally ill adults (end of life) bill would ban AI from any involvement in assisted dying.

For an hour, the peers speculated that future chatbots or algorithmic advertising or even a putative artificial general intelligence may funnel people towards assisted death, or somehow coerce people into suicide, or that doctors may be fooled by fake voice recordings.

“AI does now have the ability to create persons,” said Elizabeth Berridge, a former schools minister. Perhaps people wanting assisted death may watch YouTube to fool doctors into giving permission, yet the bill was silent on this and other issues.

Related articles:

And what if AI was used to assess patients because doctors did not want to be involved, she asked. “Speaking as a layperson,” said Berridge, “if you’ve got a very small pool of practitioners, if we do have some form of AI being used, does that not affect the creation of the AI tool itself?”

Other peers pointed out that since many diseases are now partly diagnosed with AI assistance, since paralysed patients communicate using AI tools tracking their eye blinks and since AI is used to analyse GP records to find patterns of illness – not to mention transcribe video calls – Coffey’s amendment would make the law entirely unworkable.

Charles Falconer, the bill’s sponsor in the Lords, responded to the debate by saying he had already promised to draft an amendment dealing with digital advertising.

On the basis of this promise, Coffey withdrew her amendment – like every one of its 65 predecessors.

Filibustering – the deliberate delay or block of a vote on legislation – has been going on since Cato the Younger obstructed Julius Caesar, and is usually reserved for describing marathon speeches lasting hours or days. Does a discussion about AI count?

“These amendments and discussions are really important but they should be part of secondary legislation,” said Hannah Slater, who has breast cancer that has spread to her brain and uses an AI tool to help her see after going blind in her left eye. “And particularly not part of the debate in the Lords. That’s what to me makes it clearly a filibuster.”

The 38-year-old, who has a three-year-old son, was told last summer she had about 12 months left to live and would like to be able to choose the manner of her death.

“There are so many topics that are relevant, but it’s about the intention,” she said. “This is so out of step with what normally happens, it feels quite clear to me that the intention is to delay or block the bill. “I think it’s outrageous that a small group of people in the Lords is doing this.”

Analysis by The Observer shows that six peers are responsible for half the amendments: Tanni Grey-Thompson, Finlay and Coffey, and Guy Mansfield (Lord Sandhurst), Alex Carlile and Paul Goodman, who have tabled 623 amendments between them.

During the first seven debates, opponents have taken up 90% of the debating time, according to assisted dying supporter Humanists UK, with Finlay speaking for nearly three hours of the 35 hours of debate.

The peers opposing the bill have developed particular themes in their contributions. Finlay focuses on the difficulty for doctors in establishing whether someone might have been coerced, Grey-Thompson speaks about the risks to disabled people and Coffey focuses on devolution, since the NHS for Wales is separate from England. Carlile, a KC, has pushed for high court judges to make decisions rather than a panel.

The overall effect is an argument against Commons decisions at the heart of the bill, rather than technical revisions.

The terminally ill adults (end of life) bill would allow a mentally competent adult with less than six months to live to be assisted to end their life, subject to approval from two independent doctors, overseen by a panel, including a lawyer, psychiatrist and social worker, with a cooling off period.

The opposing peers do not accept this model. Assessing someone’s mental capacity requires a High Court judge, Carlile has argued. Six-month diagnoses are too inexact.

Harold Carter, a former government lawyer and opponent of the bill, had an example: someone given a 5% chance of living for 10 years, “because he was suffering from an advanced, aggressive cancer.

“That was 21 years ago and, as far as I know, I am still here,” Carter said. “Noble lords will correct me if I’ve got that wrong. It does sometimes feel slightly otherworldly listening to these debates.”

Peers on both sides of the argument are supported outside the Palace of Westminster by networks of pressure groups. Dignity in Dying has been campaigning for euthanasia since 1935, but sits apart from a coalition of other groups, which include My Death, My Decision, founded in 2009 by former Dignity in Dying members unhappy that it was only focusing on the terminally ill.

Others include Humanists UK, which has funded high court challenges by people seeking the right to an assisted death.

On the other side of the debate is a combination of disability and religious groups, including Disability Rights UK, Not Dead Yet UK and the Salvation Army, as well as Care Not Killing, which was founded in 2006 by groups including the Association for Palliative Medicine, and is linked to the Christian Medical Fellowship and Christian Action Research and Education.

Since the bill was introduced, several medical colleges that represent doctors have shifted to oppose it, including the Royal College of Psychiatrists and the Royal College of Pathologists, while others representing GPs and surgeons have remained neutral.

Many opponents believe it is entirely proper for the Lords to be able to block the bill, whether by filibuster or vote.

Labour MP Kim Leadbeater began the process with a private member’s bill, which does not have government backing, and the Lords constitution committee held that it was “constitutionally appropriate” for peers to reject it.

Even so, there are those who worry that the public may disagree. Around four-fifths of the British public support the principle that doctors should definitely or probably be allowed to end the life of a terminally ill patient if they request it, according to the National Centre for Social Research. In a previous debate, Elizabeth Butler-Sloss, the first female lord justice of appeal, said peers should try to make the bill work.

“If we do not,” said Lady Butler-Sloss, “there is a very real danger that the reputation of this House, which not only I, but all your lordships care about deeply, will be irreparably eroded.”

Photograph by Henry Nicholls/Pool/AFP via Getty Images

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy