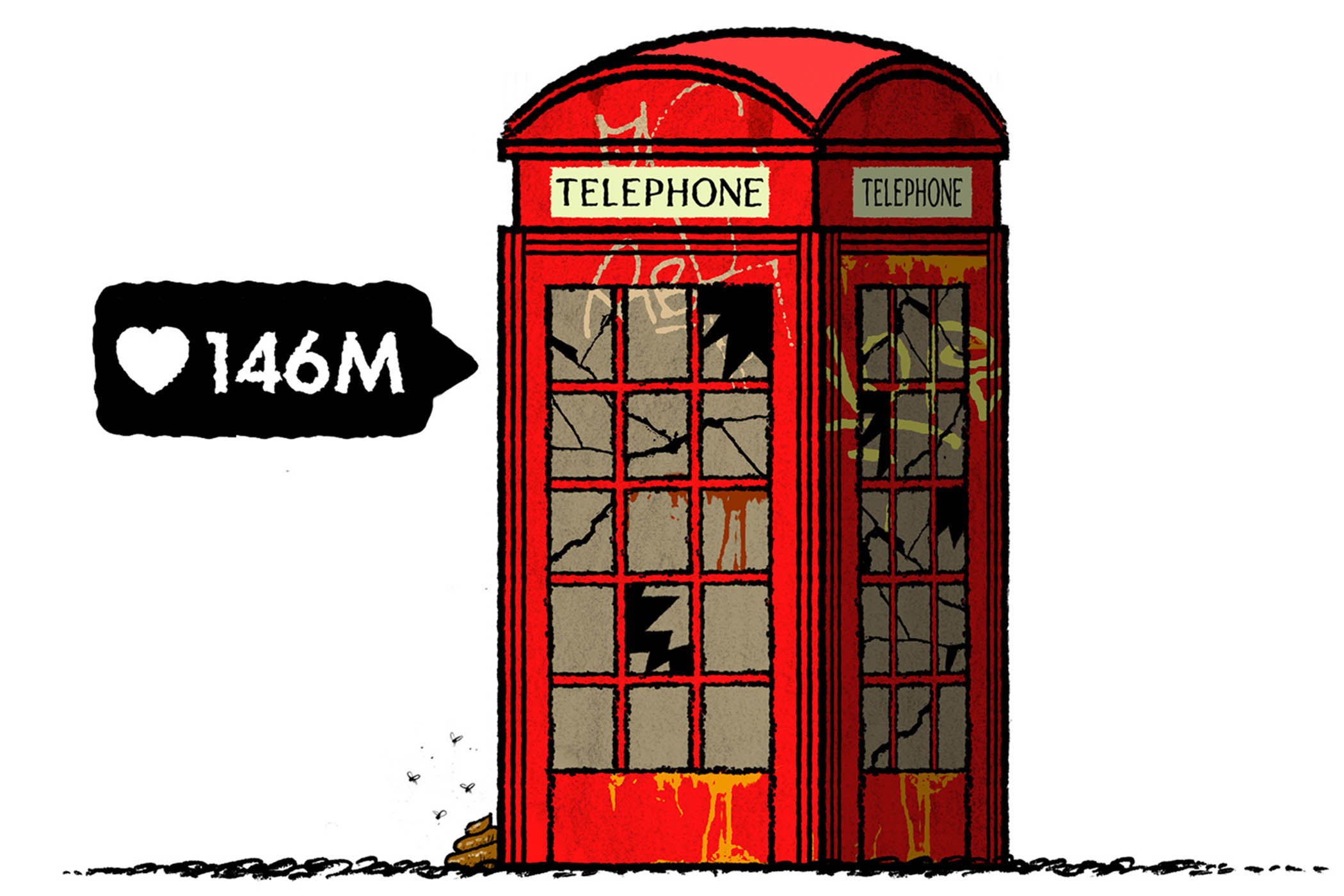

Britain’s experiment with car sharing – once hailed as a way to wean cities off private cars, unclog streets and bring on the electric vehicle revolution – has reached a sticky moment. Zipcar, the business that symbolised the movement, is pulling out of the country, leaving behind a patchwork of smaller operators, stranded users, confused policymakers and irate environmentalists.

At present, Londoners can rent these cars off the street for between £6 and £15 an hour, a price that includes fuel, insurance and breakdown cover. They use them for anything from trips out of the city to moving house. Last week, however, the US company, owned by Avis Budget Group, announced it would withdraw all its vehicles from the capital at the end of the month.

That leaves a gap. Now its 650,000 registered UK members will either have to buy their own car, give up getting about or switch to a rival. But their options are scant. They include the rental firms Enterprise and Co Wheels, which operate across the country, as well as peer-to-peer companies such as Hiyacar and Turo, which allow users to lend and borrow each other’s cars. Then there are between 15 and 20 smaller schemes, mostly rural, sometimes publicly funded, in which a group of people share a car. But in London none of these will easily replace Zipcar, which has about 90% of the market.

Nationally, car clubs own more than 5,300 vehicles in the UK, of which Zipcar accounts for about 3,000. These companies do better in densely populated areas, so London seems an unlikely place to fail.

Many people will be tipped into car ownership instead, which is bad news for the environment. Cars, vans and lorries are together responsible for about 30% of Britain’s greenhouse gases. Sharing companies help chip away at this because they nudge people away from buying their own vehicles, and that tends to reduce the number of trips people take. One survey finds 22% of users sold their cars after getting used to sharing. CoMoUK, a transport charity, reckons each car club vehicle on average takes 27 private cars off the road.

Car clubs can be climate-friendly in other ways too. According to Richard Dilks, chief executive of CoMoUK, about 30% of the company’s vehicles are electric, compared with about 4% of all licensed vehicles in Britain. But as costs have risen this figure has dropped, he says, from about 35% in 2023. It now costs about £6,200 extra to operate one of these cars, and users don’t like having to charge them.

Private cars also line streets and flow on to pavements, which is an increasing problem. One estimate suggests car sharing has freed up an area the size of Hyde Park. Across Europe, “carspreading” is on the rise: these hunks of metal are becoming heavier, wider and longer. Meanwhile, the number of cars in Britain is growing every year. Greg Marsden, professor of transport governance at Leeds University, says this is an urgent problem. “Around a third of cars don’t move on any given day,” he says. “We need a load of them off our streets, and car clubs can help with that.”

What went wrong? Some of Zipcar’s problems are specific to London. Each of the 33 local authorities in the capital has its own processes and prices, which can be tricky to navigate. Contracts have to be negotiated separately, and expire at different times. And in January a new £13.50 daily congestion charge will be introduced on electric vehicles and will apply to any journey that passes through central London.

Related articles:

But other roadblocks to a car-sharing revolution are national. Insurance premiums are one issue: costs have risen sharply for the past five years or so. Local government everywhere is increasingly strapped for cash, and has been asking for more and more money from car clubs, particularly in hotspots. At present, Zipcar reckons users save on average about £3,000 a year compared with the cost of owning a car. But if prices rise to keep pace with costs, that calculation will start to look different. All in all, it is hard to see how a smaller company can step up and fill the space without encountering the same problems.

So is the car-sharing revolution doomed? Not in some other countries. The UK lags behind the rest of Europe: we have fewer than one car-club vehicle for every 10,000 people, while in Belgium that figure is 6.3, in Germany 5.4, and in France 2.1. The Netherlands, Ireland and Italy are also ahead of us.

The difference seems to be that in places such as Germany there is strong government support. A car-sharing act in 2017 there meant dedicated parking spots and fee reductions for these vehicles, treating them similarly to taxis. Marsden says new housing developments have also kept car sharing in mind, swapping out private parking. Subsidies, insurance cuts and promoting car sharing in general would help too.

But those things may not work without investment in other types of public transport. Sharers also tend to use buses, trains and bikes. But if these options aren’t reliable, says Dilks, “the whole thing doesn’t stack up”. Outside the big cities, Britain’s bus network is notoriously bad, and bike lane schemes leave much to be desired.

The core problem seems to be that policymakers like the outcomes of car sharing but don’t want to treat it as a public good. As Marsden asks: “Is it just a commercial product, to make money from, or do we want to invest because we believe in it?”

Photograph by Dan Kitwood/Getty Images

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy