The World of the Cold War

Vladislav Zubok

Pelican, £25, 544pp

In the second week of October 1962, senior Soviet military officers in Cuba made the important discovery that palm trees don’t give much cover. It was impossible to hide ballistic missiles among them when American spy planes were directly overhead. A warning was sent back to Moscow but no one was brave enough to pass it on to Nikita Khrushchev, the Soviet premier.

Khrushchev was on a mission. He was determined to show the young President John F Kennedy that if he insisted on a free hand for the US in Berlin, Russia would assert the same right to provoke in the Caribbean.

The Soviet strategy was not much more sophisticated than that. But it was enough to set in motion a Russian armada of 82 ships carrying 44,000 troops and several batteries of tactical and intermediate range nuclear missiles. Nothing could hide them either, and on 16 October the CIA told Kennedy all about them.

Vladislav Zubok argues in The World of the Cold War that it’s “wrong and dangerous” to suggest – as revisionist scholars have begun to – that the Cuban missile crisis did not in fact bring the world close to thermonuclear war. Zubok’s case is that Khrushchev was improvising; that this forced Kennedy to respond in kind; and that the world was saved as much as anything by luck.

There was no playbook, no hotline and plenty of scope for events to spiral out of control

There was no playbook, no hotline and plenty of scope for events to spiral out of control

There was no precedent, he argues, no playbook, no hotline and plenty of scope for events to spiral out of control, thanks not least to a Soviet command and control system that let field commanders authorise the use of tactical nuclear weapons. His analysis is compelling and timely. Zubok, a professor of international history at the London School of Economics, first proposed it in an article for Foreign Affairs in 2023, when there’s little doubt it will have fed into the thinking of the Biden administration in its response to nuclear threats from Vladimir Putin over Ukraine.

Zubok’s larger thesis in this book, however, is harder to accept. He puts it very simply: “I side with those who claim that the cold war was caused by the American decision to build and maintain a global liberal order, not by the Soviet Union’s plans to spread communism in Europe.”

The second half of this argument is less controversial than the first. Stalin explicitly foreswore communist internationalism in favour of consolidating his power within the sphere of influence agreed to by Roosevelt and Churchill at Yalta. And after Stalin’s death, Zubok writes, “there was no cold war strategy inside the Kremlin”.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Instead, there were the bizarre leadership styles of Khrushchev and Brezhnev – a mix of paranoid and reactive. Many of Khrushchev’s decisions were gut calls forced on him by the Soviet Union’s chaotic efforts to catch up with the US in the arms race. His pronouncements were largely propaganda. Russia would churn out nuclear missiles “like sausages”, he declared, knowing it could do no such thing. The “sword of revenge” would hang over imperialists, he said, after detonating a colossal 50 megaton H-bomb in the Arctic in 1961, knowing full well it was far too big for any of his planes to carry.

As for Brezhnev, he was reacting to the madness of MAD. Mutually assured destruction was so obviously a bad return on the sacrifices of the Great Patriotic War and Stalinism that languid Leonid sought détente instead.

But if it’s reasonable to question the idea that a grand plan to spread communism in Europe caused the cold war, blaming it on American efforts to build a global liberal order is a stretch. Zubok’s argument here depends heavily on his view of the American post-second world war elite as driven by a belief in their exceptionalism and defined by their chauvinism. “Myths of Anglo-Saxon superiority in a white democracy built by immigrants of European stock built a democratic, but also racist foundation for American foreign policy,” he writes.

This may be true, but it discounts a factual record. The US’s postwar leaders had won two world wars and the race to the A-bomb and the H-bomb. They’d built Nato and delivered the Marshall Plan, and they’d constructed an economy that delivered butter as well as guns. Stalin built the gulag and crushed social democracy across Eastern Europe. Khrushchev sent tanks into Budapest in 1956; Brezhnev to Prague in 1968 – all chilly stuff.

The world of the cold war was bigger than Europe, of course. Other overviews have shown how Korea, Vietnam, China and parts of Africa were at times the central focus of the conflict. Zubok tries to give due weight to the Soviet perspective in a field dominated by American ones. It’s fascinating to learn, for instance, how Stalin’s people wanted the official translation of “containment” to be “strangulation”. But there is a sense here that the Soviet archives have hung on to most of their secrets; and maybe always will.

Order The World of the Cold War at observershop.co.uk to receive a special 20% launch offer. Delivery charges may apply

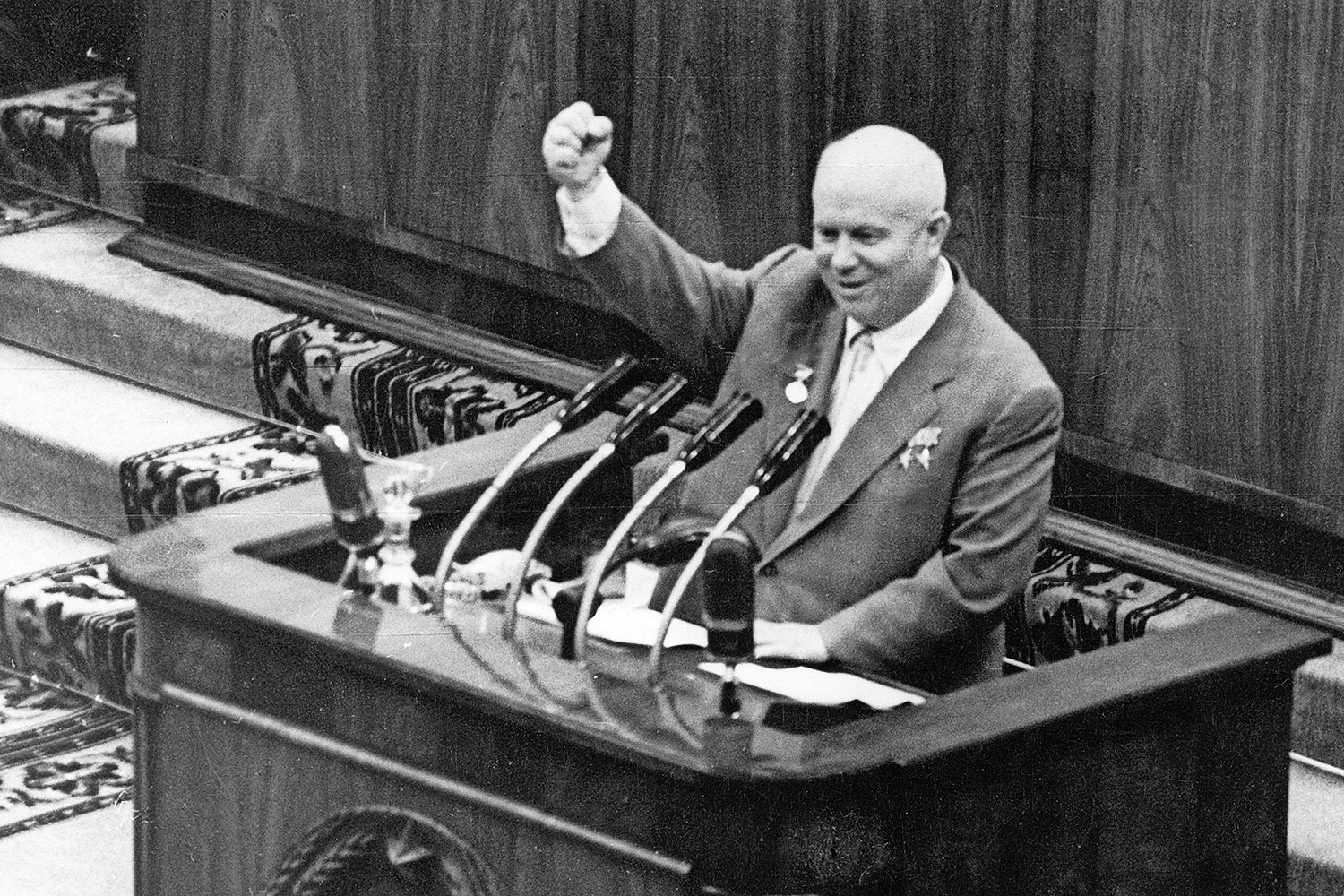

Photograph Sovfoto/Universal Images Group via Getty Images