The practice of medicine has changed profoundly since I started training as a surgeon 45 years ago – not the nature of the operating, or the anxiety and suffering of patients, but the way doctors work. This has been driven by the increasing cost of an ageing population and new and expensive medical technology. It is in the nature of power to seek to control everything around it and suppress any alternative sources of authority.

Successive UK governments – especially since 2009 – have tried to contain rising costs and silence complaints and warnings from the medical profession by introducing a new class of managers into the NHS. Doctors have lost most of the agency and autonomy they once had. They have not lost, however, the responsibility for what happens to patients.

This combination of responsibility with little autonomy – where you get blamed for things that are out of your control – is highly stressful and it is not surprising that doctors in the NHS are demoralised and alienated. How can an organisation flourish if so many of its members have lost commitment to it, made even worse by knowing that they are often providing a second-rate service?

The fact that something has gone seriously wrong with the NHS is shown by the staggering statistic that more than twice as much is spent on medical litigation over obstetric care than is spent on delivering the care itself. The strike by resident doctors and the threatened strike by nurses are about pay, but they are also about the transformation of professionals with a vocation into alienated employees.

Showing a quite terrible ignorance of healthcare, Margaret Thatcher declared that the introduction of management into the NHS would make it so good that nobody would want to pay for private care. Although the extra cost of the new class of managers is small compared to the overall cost of the NHS, or compared to management costs in other healthcare systems, the cost in terms of lost productivity and commitment from NHS staff has been many times greater.

My surgical colleagues are lucky if they get to operate more than one day a week, and when they do operate, they get much less work done than I did. It is extraordinary just how inefficient the department I used to work in has become over the last 20 years. As for the resident doctors – as junior doctors are now called – despite Brexit, they work the rotas that come with the short working week of the European Working Time Directive (EWTD). This was designed for assembly line workers in factories. The continuity of care that patients enjoyed when I was a junior is a thing of the past. I got to know my patients! The resident doctors and their patients are now part of an assembly line. This is bad for everybody.

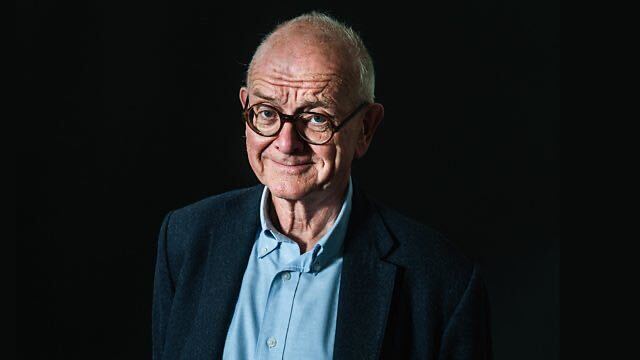

Neurosurgeon and author Henry Marsh. Credit: BBC

I realise that I sound like an old man complaining that things are not as good as they used to be. There are many things that are better in the NHS than in the past: it is (probably) safer despite all the recent scandals, there is more supervision of trainee doctors, and they do not have to work the 120 hours a week that I used to work. The senior doctors are no longer at risk of being corrupted by the unquestioned authority they had in the past. But something vital has been lost by treating state-funded healthcare as though it were some kind of business.

I still believe passionately in the NHS – as Nye Bevan said, no society can consider itself civilised if the quality of your healthcare depends on your wealth. Would I do it all over again and train as a surgeon? Just as the NHS has changed, so have I changed. The question is therefore somewhat meaningless. But when I think of the burden of responsibility I used to carry, and how it has pursued me even into retirement, and hear of the humiliations and frustrations that my colleagues at all levels must now put up with, I have serious doubts about the future of the NHS. And would I recommend a medical career now to my grandchildren? I would hesitate.

Related articles:

I have very mixed feelings about the strikes; it seems that others do too. The number who took part in the recent five-day strike was down by 7.5% on the previous round of industrial action, but nurses may still go on strike. I see medicine as a vocation and hence am unhappy about industrial action, but at the same time I can see how the resident doctors are treated with what amounts to contempt, with none of the training, respect and support that my generation received. When they look into their future and see their demoralised seniors, their disillusion is made all the greater.

What is to be done? There is no single or simple solution and the problem of rising costs is not unique to the UK. I would certainly abandon the EWTD and pay the resident doctors more for working longer hours. More money needs to be put into the NHS – “reform” alone is not enough. There are various options: a dedicated “hypothecated” health tax, a hybrid insurance system as exists in the Netherlands, or making wealthier people pay to use the NHS. Close on 3% of the NHS budget now goes in medico-legal expenses and this is continually increasing. Some kind of compensation system is urgently required, avoiding litigation with all its attendant costs. These solutions are all difficult and require bravery and honesty from our leaders. Otherwise, the NHS will continue its long decline.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Confessions of a Brain Surgeon will air on BBC Two on Monday, August 18