‘There ain’t no black in the Union Jack, send the fucking bastards back.” It was a common chant in football grounds in the 1980s, directed at black players, and at black fans, too.

Britain is a very different place today, that old raw racism much diminished, both on the terraces and in wider society. Yet, the question of whether there is, or should be, any black in the Union Jack – and how much – has returned, not as racist chants but in academic reports and newspaper columns.

Last week, the academic Matt Goodwin published a report that suggested that “the White British will become a minority in the UK by the year 2063”, a claim splashed across the pages of newspapers and discussed on social media.

As racism has diminished, discussions of identity have become more fraught

As racism has diminished, discussions of identity have become more fraught

The report’s methodology has been ridiculed by critics, for instance for defining as “white British” people “who do not have an immigrant parent” (which would exclude King Charles and Nigel Farage’s children). Nevertheless, alarm about white Britons becoming a minority has a long history. “UK whites will be minority by 2100,” ran an Observer headline a quarter of a century ago. Over the past decade, there have accumulated many dire warnings about white decline.

The irony is that this debate about whiteness and Britishness has resurfaced at a time when Britain has become far more liberal in its attitudes to race and identity. As racism has diminished, discussions of identity have become more fraught. Such debates have also served to allow racism to rebrand itself in the language of identity and to reshape perceptions of nationhood and of whiteness.

Nationalism is often seen as embodying one of two forms: civic or ethnic. Civic nationalists view national identity as emerging from shared political values and institutions. Citizenship is not defined by ethnic background. For ethnonationalists, a nation is demarcated by ethnicity and by shared history, language and culture.

Despite the tendency to see civic and ethnic conceptions as starkly different, in reality most nations contain elements of both. In recent years, though, the “ethnic” component has become more assertive, largely because of a sense that civic models possess insufficient heft to bear the weight of national belonging. People worry about fraying social bonds and about immigration disrupting national cohesion, turning Britain into “an island of strangers”, as Keir Starmer recently warned. To preserve a strong sense of nationhood, many insist on a renewed emphasis on the “indigenous” peoples of Europe, and their history and culture. Hostility to the universalism of liberal elites expresses itself as a celebration of ethnicity and place.

Three years ago, the Hungarian prime minister, Viktor Orbán, a political hero in many conservative circles, insisted that countries in which “European and non-European peoples live together… are no longer nations” but merely “a conglomeration of peoples”. The erasure of whiteness was the undoing of “Western civilisation”. “The West in its spiritual sense,” Orbán claimed, “has moved to central Europe” because only there do nations refuse “to become peoples of mixed-race”. The speech caused outrage but revealed how notions of whiteness and nationhood are being remade.

Related articles:

Conservative perceptions of whiteness today draw less upon 19th-century claims of white supremacy than on ideas incubated within postwar far-right circles. Alain de Benoist, one of the founders of the French Nouvelle Droite, recognised the need, in the wake of Nazism and the Holocaust, to move beyond discredited arguments of biological racism. He appropriated liberal ideas about pluralism, repurposing them for racial ends. The mixing of cultures, he argued, diluted them, so damaging diversity and diminishing differences. Europe had to ban immigration and become the homeland of white people and white cultures by excluding and repatriating non-whites. Many of these arguments have since migrated from the far right to the mainstream.

“By the end of the lifespans of most people currently alive,” Douglas Murray wrote in his 2017 bestseller The Strange Death of Europe, “Europe will not be Europe and the peoples of Europe will have lost the only place in the world we had to call home. ” Whiteness in such accounts expresses a sense of both pride and loss; an insistence on cultural superiority and specialness, but also a lament for a world slipping away.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Questions about immigration and national identity, about numbers and cohesion, about multiculturalism and integration, are all important. Posing such issues as anguish for the loss of whiteness is, however, a form of deflection, racialising the problem to avoid truly thinking about it.

Goodwin suggests that Britain becoming minority white matters because of the impact on “the symbols, traditions, culture and ways of life of the traditional majority group”. None of these, though, are coded by skin colour.

Nor is there a single tradition, culture or way of life that defines Britain. The Britain imagined by the Levellers, the Chartists and the Suffragettes is very different to that envisioned by Cecil Rhodes, Lord Rothermere or Enoch Powell. There were white people who chanted racist slogans and physically attacked me. And white people who stood on picket lines alongside the Asian women strikers of Grunwick. There are Muslims who today stand for free speech; and white advocates for blasphemy laws.

We should not conflate peoples and values; still less values and skin colour. The values that define a nation are hugely important but always contested. It is through that contestation that we begin to define what it means to belong. The debate we need is about values, not whiteness.

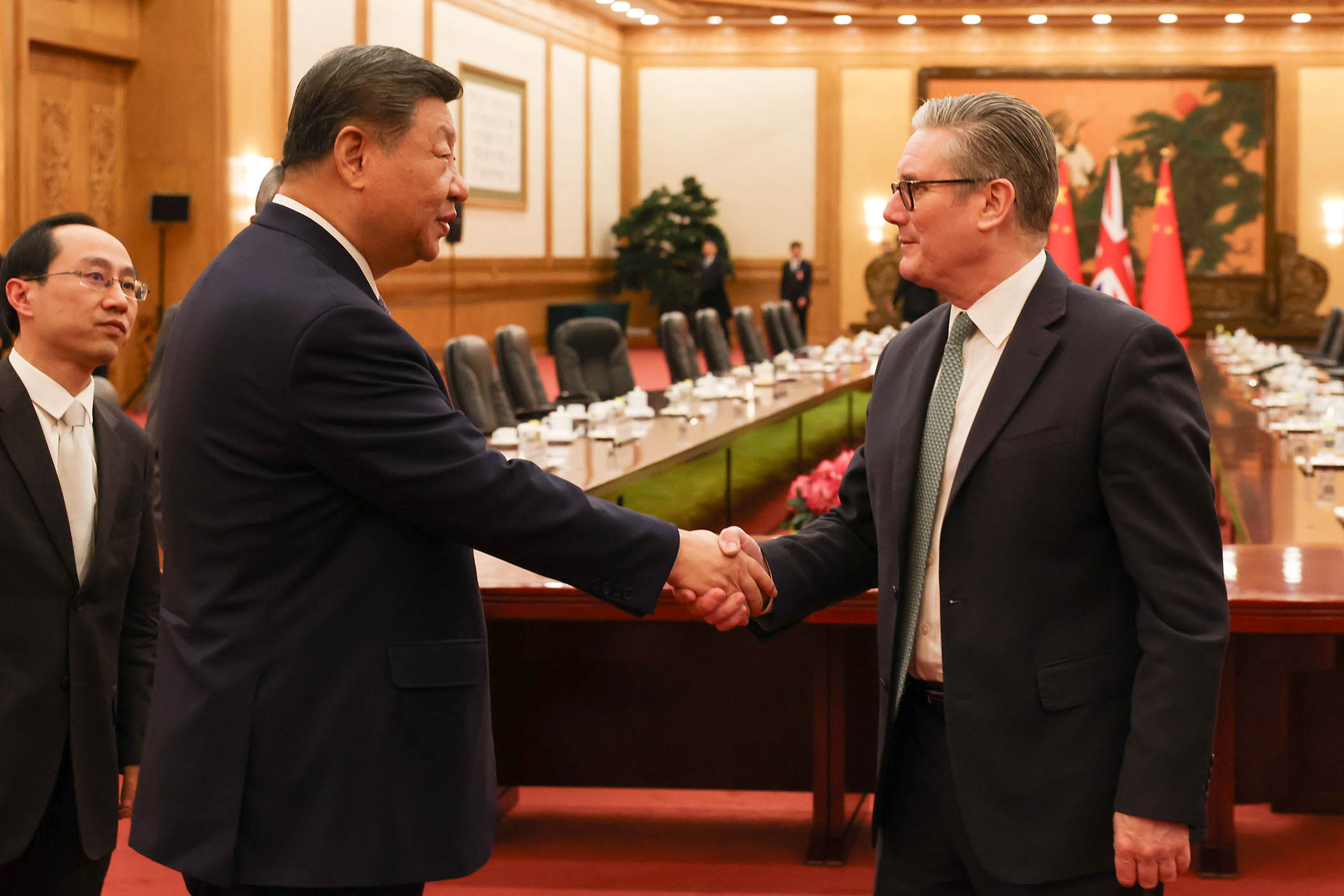

Photograph by Peter Powell/AFP via Getty Images