In the middle of the 19th century a young man called Edward Edwards had a dream in which access to knowledge was given to everyone.

His dream would take the form of free public libraries – the first of them in Manchester, the beginnings of a system that we continue to use and enjoy today: palaces of knowledge for all people. One hundred and seventy five years ago this year, Queen Victoria gave her assent to “an Act for enabling town councils to establish public libraries and museums”, that enabled local authorities of a certain size to levy a ha’penny on the rates to establish a free public library.

All praise to Manchester for being the first enlightened administration to take up the opportunity. Their library opened on 2 September 1852 and Edwards became its first librarian. The people of Manchester wanted their new institution to provide “increased and wholly gratuitous facilities for the diffusion of knowledge and for mental culture among all classes…”, bold ideas that still resonate with us today, as modern library users are given access to an astonishing array of books, music, digital resources, expert guidance in using digital services, support for businesses, and opportunities for enriching their “mental culture” – all free.

Manchester’s library grew rapidly. In 1854 its book stock stood at 25,000, and it issued those books more than 142,000 times. Last year the Greater Manchester library service welcomed 7.7 million visitors across their 133 libraries, and engaged with 80% of the state schools. Their 3m books in the collection were loaned 3.8m times, on top of which more than 450,000 eBooks and more than 670,000 audiobooks were borrowed. Manchester is one of our nation’s greatest public library systems – a true palace for the people – and under the leadership of Neil MacInnes it is in the rudest of health.

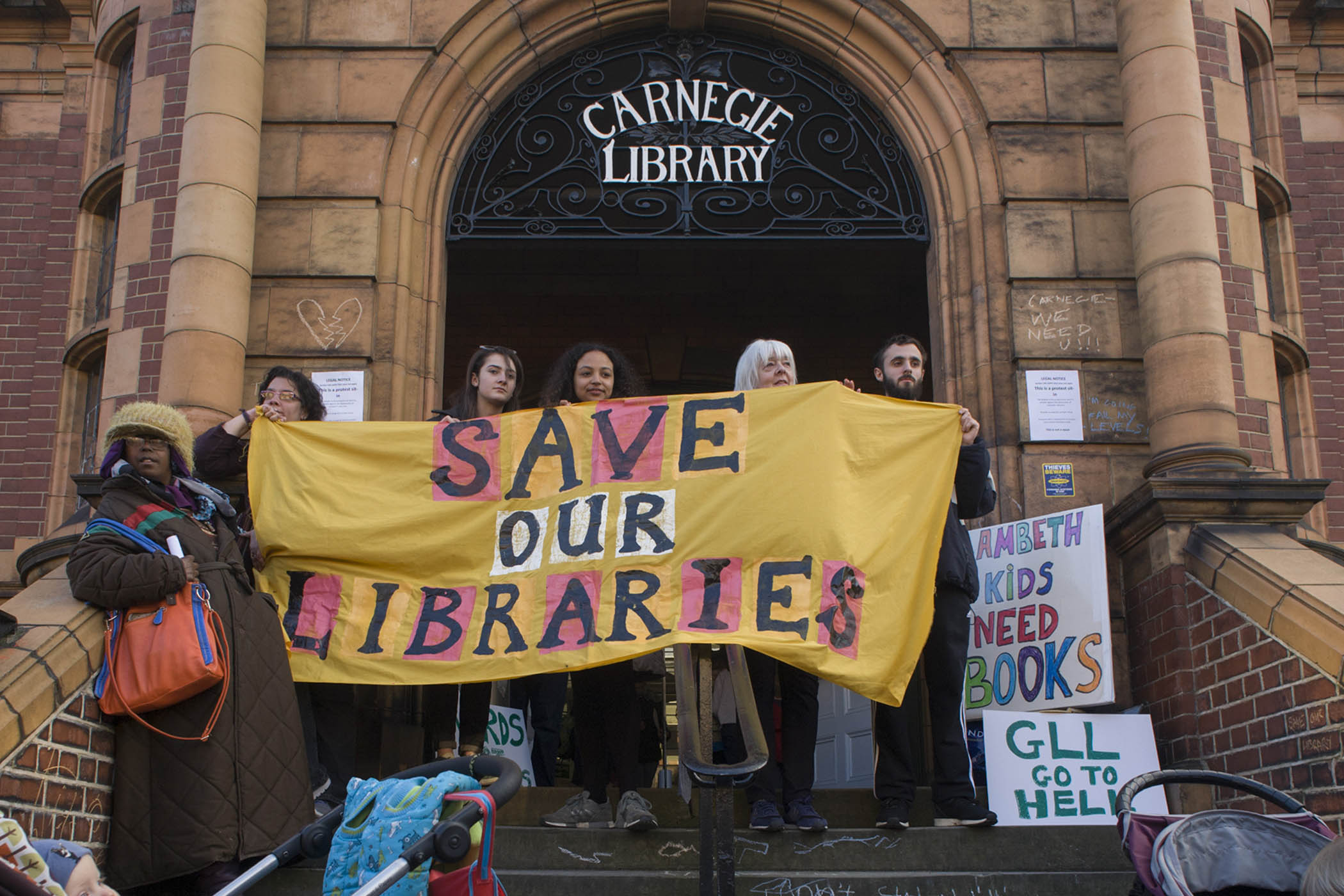

More than a decade of austerity has, however, ravaged the public library sector in many parts of our nation. There are fewer palaces for the people, many are open for fewer hours than before 2010, and some of them are in dire need of physical repair.

Net expenditure by local authorities on public libraries fell by almost half (47%) in real terms between 2010 and 2023. Since 2016, there has been a net loss of 183 libraries that came under councils’ statutory services and about 2,276 FTE library posts have been lost. There is, furthermore, evidence that poorer areas are disproportionately affected by library cuts and closures. Across the UK 7% of libraries in the most deprived decile have been closed since 2016, compared with 3% of libraries in the least deprived.

Our public libraries are free in three critical senses. First, they cost nothing to join and to use. Second, they are open to all in our communities. We must also add a third concept of freedom: the freedom to read – to engage, without restraint, a diversity of knowledge and opinion, the latter of which is being threatened today, as shown in the powerful new documentary The Librarians, which deals with the epidemic of book-banning in US public and school libraries.

The cost of creating the Manchester free library was not purely through the taxpayer. For Edward Edwards, libraries “are pre-eminently institutions for ALL CLASSES”. The wealthy should “give liberally for the education, the refinement, and for the rational amusement for those whose lot it literally is to ‘live by the sweat of their brow’’’. He felt “it is a better thing for both to unite their contributions, in such proportions as they can”. Generous Mancunians funded the first building.

Today we have even more billionaires… What are they doing to support the diffusion of knowledge and the mental culture of all?

Today we have even more billionaires… What are they doing to support the diffusion of knowledge and the mental culture of all?

As the free public library movement took hold, a billionaire became inspired to build palaces for the people across the globe. As a young man in Scotland, Andrew Carnegie’s life chances were transformed through access to books. He gave his wealth back through funding more than 2,500 libraries worldwide, 660 of which were in Great Britain and Ireland. In 1901 he gave $5m – a staggering sum at the time – for the New York Public Libraries to build an entire system of branches – 65 of them!

In our society today we have even more billionaires than in the age of Andrew Carnegie. What are they doing to support the diffusion of knowledge and the mental culture of all? We need a new Carnegie. Could one of the tech moguls making insane amounts of money emulate the Scotsman’s commitment to freely available public institutions of knowledge?

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Some tech giants have argued that their platforms are “public squares”, but social media is far removed from publicly owned and controlled organisations that are genuinely open to all, and where no money or data is exchanged for what they offer.

Could our government seize anew the spirit of public, social and economic improvement that the Victorians brought to bear on our libraries, and encourage bold, enlightened philanthropy through a matched funding scheme? A new national fund for libraries could be established if Carnegie-scale transformative philanthropy were matched by government funding.

Such a fund could be used to upgrade libraries’ physical estate, it could support the training and development of librarians, replenish the bookstock (both physical and digital), empower new digital initiatives to help safeguard local data, and help build capacity. It would be consistent with the duties of the libraries minister to “superintend” the provision of library services, ensuring it is even across the nation, that standards are set, and that the sector can develop as a whole.

Next year has been designated a “National Year of Reading”, a very positive development in which at this week’s Labour party conference, the chancellor, Rachel Reeves, committed to more than £10m in funding for a library in every state primary school by 2029. What was missing from the announcement was whether the recurrent cost of funding school librarians was also included: “A pile of books is no more a library than a crowd of soldiers is an army” to quote Gabriel Naudé in his Advice on Establishing a Library – words that would be well heeded by the chancellor and the culture secretary.

We must take this moment to celebrate the creation of our public library system, and to thank Edward Edwards and the other pioneers who made it possible. We owe it to the citizens of today and in the future to renew our library system, through a combination of government funding and philanthropic investment, to refresh those palaces for the people, and ensure their doors can remain open to all.

Richard Ovenden is Bodley’s Librarian and the author of Burning the Books: A History of Knowledge Under Attack (John Murray)

Photograph by Richard Baker / In Pictures via Getty Images.