Australia is so far away from the UK, and yet it is already here. The shooting on Bondi Beach in Sydney, precisely in a place that once seemed remote from the world’s epicentres of violence and politics, is not merely another tragic local incident. It is another moment of awakening.

Until Sunday, Sydney was not Gaza and not Jerusalem. It symbolised the good life, freedom, comfort, and a nearly perfected version of western normalcy. No longer.

Precisely there, as the first candle of Hanukah was being lit, it became clear that there are no longer any safe margins. The hatred of 2025 requires no geographic proximity. Unhindered, it travels at the speed of networks, blood translated into headlines and videos, lethal bullets in places where one believed it was still possible, at least for a moment, to forget the world.

It is easy to settle for condemnation. This is the automatic reflex of an anxious era. But condemnation alone misses the point. This shooting was not only an extreme act by a father and son. It was a symptom of something deeper, of an ideological and emotional system that has turned hatred into an international language. This is no longer local hatred with a clear context but global hatred with local dialects. One war in the Middle East becomes a violent consciousness across the world. In this age, a territorial conflict turns overnight into a cultural contagion.

Antisemitism and Islamophobia function together… This is the emotional triangle of contemporary hatred

Within this mechanism, antisemitism and Islamophobia function together. They are not separate phenomena but interlocking tools, feeding, justifying, and reinforcing one another. This is the emotional triangle of contemporary hatred.

For the western racist right, the Jew and the Muslim are two versions of the same imagined threat to white Christian hegemony. For the Islamist fanatic, the Jew is a mythical enemy, a symbol of a corrupt and threatening West, a demon to be eradicated. And for the Jew, the racist western right and radical Islam are two reflections of the same historical failure, the same promise of protection by the majority that repeatedly reveals itself as conditional, fragile, and at times lethal.

This terrible triangle feeds itself. An attack on Jews in the heart of the Christian world generates a wave of hatred against Muslims, which in turn produces further radicalisation and further violence. Social media algorithms amplify and shape this reality. They reward rage, harden identities, and turn the other into an abstraction that is easy to hate. A Jew wearing a kippah or a woman wearing a hijab becomes a collective symbol, while the individual human being and their rights are erased.

Yet alongside the recognition that this fracture crosses religious, national, and cultural boundaries, a countermovement is also taking shape. The local hero who risked his life and body was himself Muslim. A righteous actor who, without knowing it, acted according to the principles of the Granada Declaration against antisemitism and Islamophobia. These principles were presented at the Doha Forum 2025 and received broad support from all participants: Muslims, Christians, Jews, believers, and secular voices from different countries and cultures. Not as a ceremonial statement, but as a shared understanding that this hatred is not the problem of one community. It is a symptom of a deep crisis in global culture itself.

The declaration seeks to reframe the struggle against hatred not as a selfish fight by minorities for their own safety alone, but as a broad civic and moral responsibility that recognises antisemitism and Islamophobia as different expressions of the same modern racism, one that corrodes institutions, public discourse, and the ability of human societies in all their diversity to endure.

Beneath all of this pulses another, deeper debate, one that has accompanied us since 1945. When the world emerged from the shock of the Holocaust, it swore, “Never Again”. But that oath was never unambiguous. It carried within it a split that has never been resolved.

For many, especially Jews, its meaning was particular. Never again to us. The lesson was that the world is dangerous, that universal promises collapse in moments of truth, and that Jews must be strong, armed, and sovereign to ensure their survival. According to this view, the Holocaust was a unique crime against the Jewish people, and the only answer to it is protective Jewish power. From this perspective, the shooting in Sydney is not surprising but confirming. Even at the edge of the world, we are hunted. There is no one to rely on but ourselves.

The Holocaust was not only a Jewish tragedy but a crime against all humanity

But there is another interpretation. A universal one. Never again to any human being. For those of us who believe in it and act in its spirit, the Holocaust was not only a Jewish tragedy but a crime against all humanity that took place in the body of the Jewish people. Its lesson was and remains an uncompromising commitment to human rights, the struggle against racism, and the protection of minorities wherever they are. Because any people can become perpetrators, and any collective can become victims. Those who swore this oath understood that the struggle cannot remain an internal Jewish struggle, because the moment it does, the surrounding culture receives a sweeping exemption from responsibility.

The tragedy of 2025 is that these two interpretations now collide head on. When Jews in Bondi are attacked, the “Never again to us” camp sees universalism as dangerous naivety. When the war in Gaza exacts a heavy human toll, the “Never again to any human being” camp experiences the retreat behind Jewish nationalist walls as a betrayal of the moral lesson of the Holocaust itself.

This is a struggle over the soul and identity of western culture as a while

And the hatred outside, the one that fires bullets in Sydney, does not distinguish between the camps. It does not ask whether the Jew is a humanist or a nationalist. It attacks identity itself. Here, the trap reveals itself in full sharpness. If the fight against antisemitism is perceived as a fight of Jews for Jews alone, it will fail not only morally but politically. This is a struggle over the soul and identity of western culture as a whole. Over the question of whether it is still capable of protecting human beings as such, or whether it will retreat into closed identities, fear, and brute force.

The challenge of this moment is not to choose between security and humanism but to understand that there is no real way to separate them. Jewish security that is not rooted in a broad human vision will always remain exposed and fragile. And a genuine struggle against antisemitism requires a struggle against hatred of the other in all its forms. Not as a slogan, but as a shared cultural, moral, and political project. Otherwise, the bullet in Bondi will not be an exception. It will be the norm.

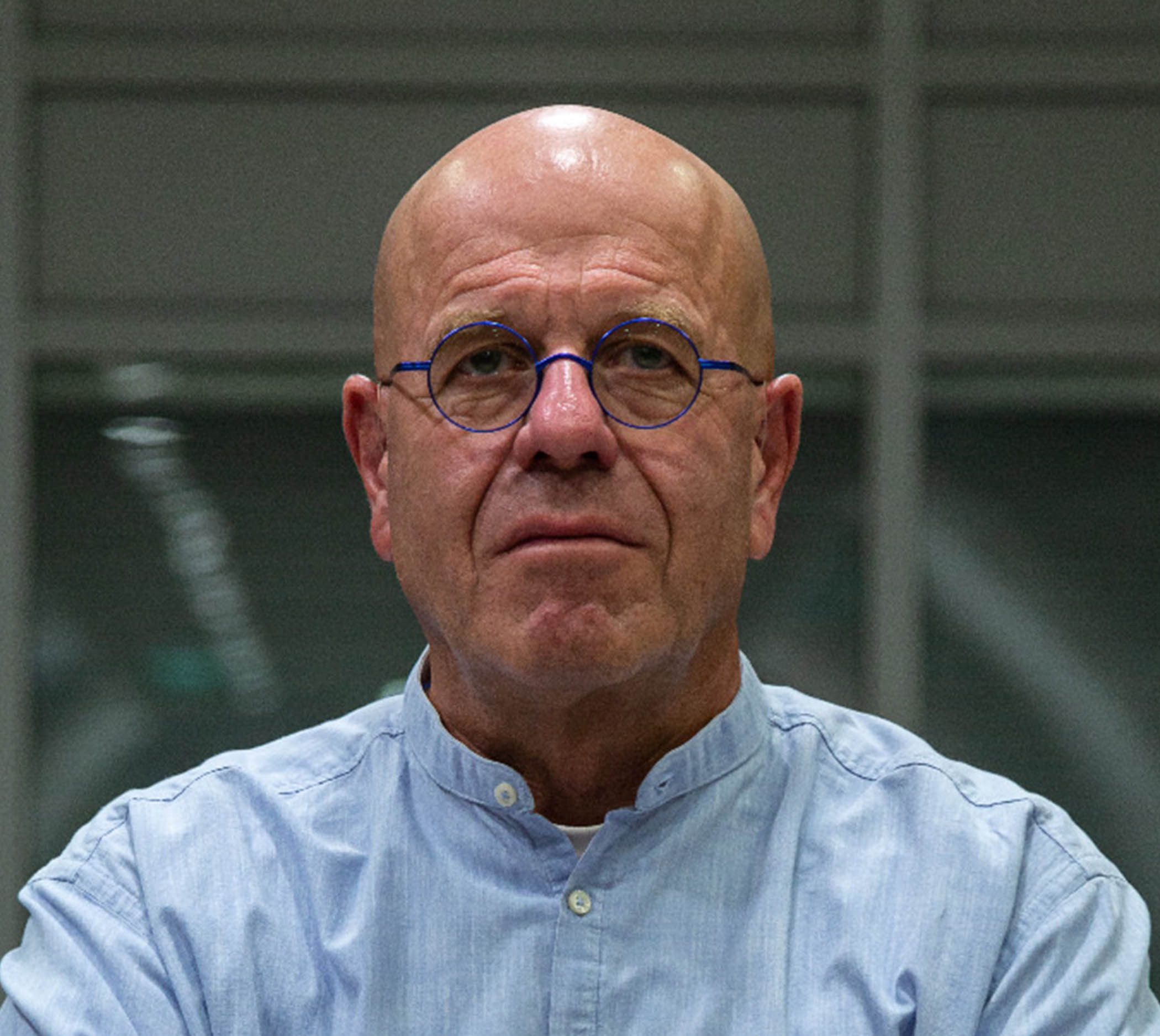

Avraham Burg is a former speaker of the Knesset

Photograph by Mark Baker/AP