‘We live in a world … that is governed by strength, that is governed by force, that is governed by power,” said White House deputy chief of staff Stephen Miller earlier this week. “These are the iron laws of the world since the beginning of time,” he added, swatting away concerns about the abduction of Nicolás Maduro and violations of Venezuelan independence and sovereignty as “legal niceties”.

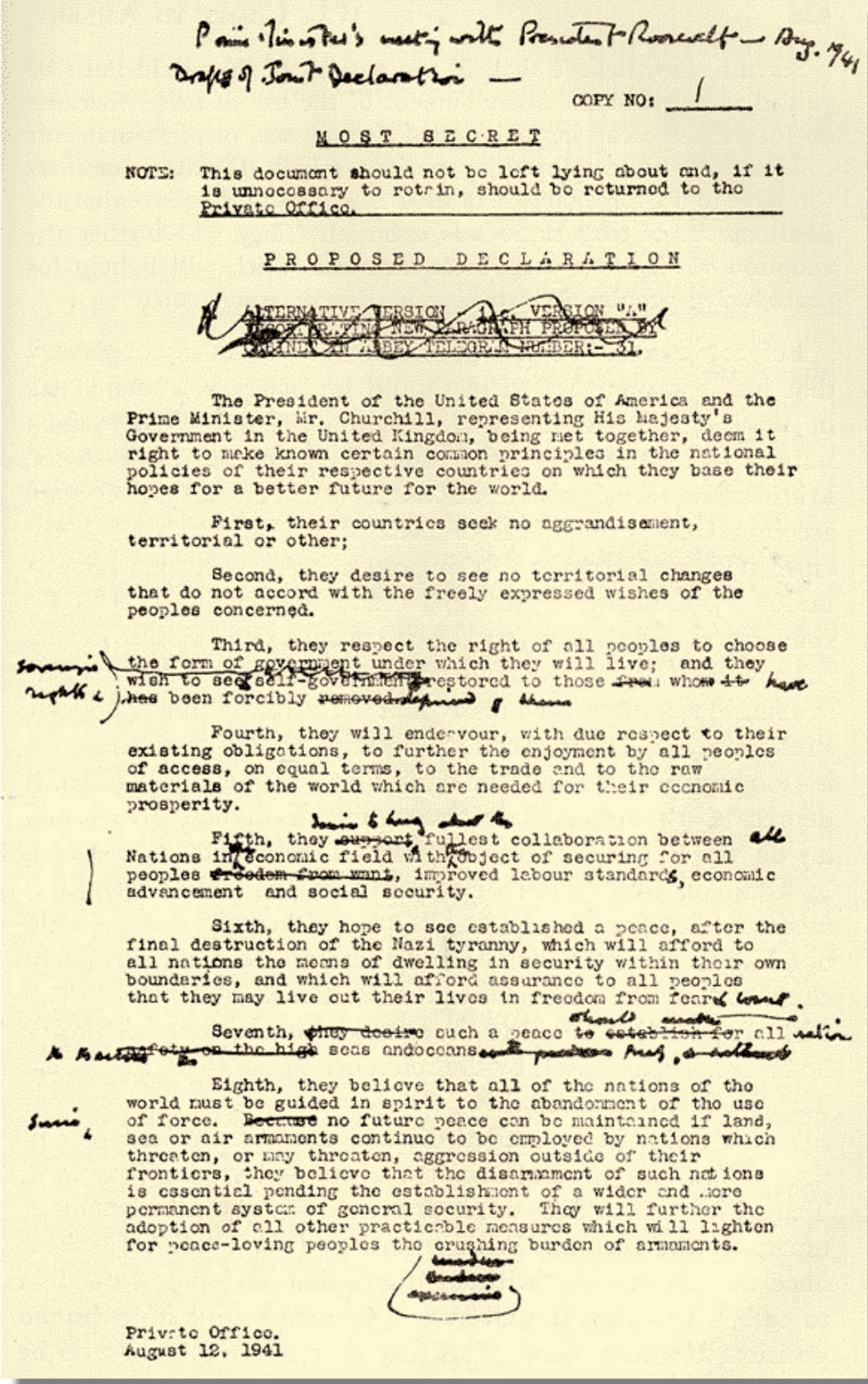

Assuming, as one probably should, that Miller speaks for President Donald Trump, the episode confirms the administration’s disdain for international rules. The president has told us that the only constraints to his actions will be “my own morality, my own mind”, not any rules of international law, including treaties ratified by the US Congress. This is a shredding of the one-page document on the future organisation of the world, written in 1941 by Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill, both of whom President Trump once said he was a fan.

The Atlantic charter proposed a new multilateral order premised on rules and institutions to prevent a recurrence of the horrors of the 1940s. The pair envisaged respect for sovereignty and self-determination, prohibitions on the use of force, rights for individuals and groups, and far-reaching multilateral arrangements to promote trade and economic liberalisation.

The document led to the UN charter, which prohibits actions of the kind that occurred last weekend in Venezuela. There is nothing unclear about its rules on sovereignty or the use of force, as Kemi Badenoch claimed this week, and we don’t need more facts to form a view as to whether or not the Maduro abduction was lawful under international law, as Keir Starmer suggested. The rules prohibit the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, allowing force in self-defence only if an armed attack occurs. Period. The charter does not admit of any exception for law enforcement activity, for example in relation to narco-traffickers. None of its provisions, and no other rule of international law, allows one country unilaterally to claim a right to the control of another country’s natural resources, as Mr Trump envisages in respect to Venezuela’s oil or the lands of Greenland.

Winston Churchill’s edits on a draft of the Atlantic Charter, 1941

The regular rules of international law make it equally clear that the abduction by one country of the head of state of another country (or a former head of state, as Maduro’s status is contested after the 2024 election) is not permissible under international law. The fact that Maduro was indicted for a crime in the southern district of New York makes no difference. The logic of the Trump administration’s claim is that other countries would be equally free to indict whoever they wish in another land, abduct them, then put them on trial. Watch out, Vladimir Putin or Benjamin Netanyahu – having been indicted by the international criminal court, you may now lawfully be abducted. The claim is absurd, the consequence mayhem.

Of course this is not the first time that someone who has been abducted in one country is put on trial before the courts of another. It happened in 1960 to Adolf Eichmann, taken from Argentina by Israel, and then in 1989 to Manuel Noriega, taken from Panama by the US. In both cases, and in others, such actions were met with strong protests of illegality. To argue against the legality of abduction is not to defend these or other individuals who have acted reprehensibly.

The English courts, too, have taken a strong line on overseas abductions. In ex parte Bennett, in 1993, the House of Lords ruled that a defendant who’d been abducted in South Africa and returned to the UK unlawfully could not be tried when the law enforcement agency responsible for bringing a prosecution had participated “in violations of international law and of the laws of another state in order to secure the presence of the accused within the territorial jurisdiction of the court”.

US courts have been more accommodating, but not yet in relation to someone who claims to be a serving or former head of state. Ironically, in July 2024 the US supreme court ruled – in a case brought by Trump – that a former US president has absolute immunity in relation to acts of core constitutional power and a presumption of immunity for all other acts. Assuming the Maduro trial will face legal challenges in relation to immunity and jurisdiction – as occurred when former Chilean head of state Augusto Pinochet was arrested in 1998 on a visit to London – the US supreme court might have to consider the consequences of its own recent judgment. Would the former head of state of another country have less of a right to immunity than a former US president?

The idea that the international rules-based system is over is simple-headed. We’ve had such rules for centuries, and we will have them for many more

The idea that the international rules-based system is over is simple-headed. We’ve had such rules for centuries, and we will have them for many more

We should not, however, focus only on the legal technicalities. The events of last weekend give rise to bigger issues for Britain and for the world. Starmer will be acutely aware of that, as he treads a fine line. His legal self will surely know that what has passed is manifestly illegal and will give rise to a multitude of dangers and headaches, including copycat efforts. His political self will tell him to keep his head down, say as little as possible and work back channels to get this sorted out as painlessly as possible, hoping to avoid future actions of the kind Miller may have in mind. Hence his stronger words on Greenland.

The trouble is that Trump is on a roll. After Iran and Venezuela, more international adventures may seem a rather attractive distraction from falling poll numbers. Maybe Cuba, as Marco Rubio seems to wish? Or Greenland? “Nobody’s going to fight the United States militarily over the future of Greenland,” Miller said, offering a provocative poke. Really? The US military moves to take over that territory and there is no military response to stop the occupation of a part of Nato territory? How is that to be squared with Britain’s position on Russia’s occupation of Ukraine?

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Judging by what has been said on the matter – the rationales offered by Trump, Rubio and Miller are wildly different – it is hard to know what the future holds for the people of Venezuela. “We have a complete embargo on all of their oil and their ability to do commerce,” said Miller. “For them to do commerce, they need our permission.” That is duress pure and simple, and economic arrangements imposed under conditions of duress tend to face serious legal challenges over the longer term.

There is the rub. Trump and Miller may not like international rules, but when it comes to selling newly acquired oils or other resources, they will have to rely on a raft of international rules to transport, process and profitably dispose of their new assets. Undoubtedly the oil company lawyers will be examining those rules rather carefully to be sure that future investments are legally secure over the long term. International rules on natural resources and financial assets, it turns out, aren’t quite so easy to get around, as Putin is arguing in relation to stranded Russian assets currently held by European and other banks.

The idea, as some are suggesting, that the international rules-based system is over is simple-headed. We’ve had such rules for centuries, and we will have them for many more.

The immediate challenge for Starmer, whose commitment to a rules-based system is strongly supported by the vast majority of countries, is what to do next in the face of so unpredictable a US administration. He will want to minimise present risks and maximise the possibilities for longer-term arrangements that allow for a decent and orderly form of global governance. The legacy of Iraq is plain, including on issues of legality, planning and exit. He will need to work out what his red lines are, what will cause him to get off the fence and then how to execute a response to protect Britain’s long-term interests when the moment comes to speak truth to the power of autocracy and lawlessness that is now on offer.

The challenge for the rest of us is no less daunting. With Trump’s actions in Iran and Venezuela, with a new US national security strategy that casts the rule of law to “civilizational erasure”, with this week’s decision to leave 66 international organisations (including the UN International Law Commission and the UN framework convention on climate change – why not the United Nations itself?) and with Trump’s “own morality” as the guiding compass to all action, the challenge to the existing rules-based system is crystal clear.

It’s time to buckle up, be ready to stand firm with others for principles and values. The moment to come may be long, and there will be tough decisions to take and surely a big price to be paid. But ultimately, as has been the case for centuries, the rules-based system, warts and all, will prevail. In a world replete with differences, international law may well be the only common language we have.

Philippe Sands is professor of law at University College London. His latest book is 38 Londres Street: On Impunity, Pinochet in England and a Nazi in Patagonia.

Photograph by Sally Hayden/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images