Geordie hubris: because I’m from the north-east and Dominic Cummings is from the north-east, I thought I understood him better than people in London do. I recognised the traits of someone from up here operating down there and thought it was his superpower – the thing that gives him the inside lane in politics. But it was more localised than that.

“The fact I worked in Klute was a huge factor,” he told me. Why? “You had to confront the realities of working-class life in all sorts of ways, including its violence. It was quite a violent place. You had to think about drug dealers and general problems of nightclub land. There’s not really any room for illusions when you’re involved with that world: you have to just face reality. Otherwise, you’ll get a terrible shock.

“It definitely had an influence on me because on the one hand, you’re walking around famous Oxford University; on the other, I was working at Klute. Extremely different environments. And I think it definitely meant that when I was doing politics, I was always thinking: ‘What would the people in Klute make of these arguments? How much would they notice? What would they care? What would they say if I was chatting with them the way I used to chat with them?’”

How much do I need to explain about Klute? What level of Cummings knowledge am I working with here? Because it’s beginner Dom, really, a wrung-out part of the Cummings legend. But I suspect we’re all shackled to the people and places of our early years, or at least to the versions our brains piece together, so I want to cover it. Sorry.

Starting in Durham, at Dom’s childhood home. Nice enough – not grand. I think students live there now. His parents went to university (dad, philosophy; mum, medicine), after which his dad did various jobs, including project managing the construction of oil rigs. His mum taught at “a normal state school”, then, his words: “One of these special schools for kids chucked out of your kind of normal school.”

From there, follow the River Wear round, past the cathedral on the opposite bank and up through the trees to the last of Dom’s four schools. He went to one in Poland (in the late 1970s while there for his dad’s work) and a state school in the north-east, but ended up at Durham School: expensive, all greenery and smart uniforms, none of which ensures happiness, of course. “I didn’t enjoy school,” he said.

Then Klute, a three-storey nightclub on the riverbank, almost hidden by Elvet Bridge. As I poked around a couple of weeks ago, a man from El Salvador cleaned the outdoor seating area. Must wafted through the closed door. It has new owners now, but in the 1990s, Dom’s dad and two uncles owned it. His uncle Phil ran it. Dom worked there during holidays.

“What I did was take the money, then kind of watch over what the bouncers were doing,” he said. “Or just do things that Phil would ask me to do. Like Phil would say: ‘Go and stand at the end of the bar and watch so-and-so.’ Or: ‘Go down there and see if those guys who came in are going to kick off.’”

Related articles:

Durham had a reputation for students clashing with local people. Or rather for students getting their heads kicked in by local people. “Everybody else who tried just got bloodbaths,” said Dom, “but Phil and Hopper made it work.” In William Norton’s book White Elephant (more on that later), he described Phil as a “short, stocky figure – not someone you would pick a fight with”. Dom described him as “a tough character, for sure, a very tough character”.

Cummings in May 2020 after speaking to the press following his trip to Barnard Castle during lockdown

Michael Hopper was Klute’s manager. “He was super-heavyweight English amateur boxing champion,” said Dom. He died in 2022, and when I phoned his former coach at Spennymoor Boxing Academy, Robert Ellis, to check the year of his death, Ellis recalled Dom watching Hopper’s title fight at the Royal Albert Hall in 1992. He later texted: “Dominic Cummings and his wife Mary are huge supporters of our club and have helped us hugely.”

When I messaged Dom to ask if he ever got punched at Klute, he replied: “Michael H saved me many times and I saw him save hundreds of people from getting their heads kicked in. He was extraordinary and a real life hero.” Hours later, at 2.32am, he added: “In maybe 1993ish I saw on Elvet Bridge five people attack a student shockingly. MH ran in alone and saved him, maybe from death. It was extremely brave and has stuck in my head ever since. He was really a highly unusual character. If you mention him in your piece you should reflect he was a hero.”

Brace for cringe: on 23 June 2016, I wore a blue T-shirt with a circle of yellow stars on it. I stuck the stars on myself. I know. The next day, I drove to Matlock with my wife. We listened to the news the whole way. I sometimes kid myself I saw Brexit coming, but we were in shock. Brexit wasn’t something that could be changed at the next election. It was irreversible. Dom had won: “Take back control.”

I looked through my emails to work out when I became interested in him. There’s nothing before 2019, the year Benedict Cumberbatch played him in the television drama Brexit: The Uncivil War. Two scenes stuck in my head. One is when he goes to the pub to speak to voters. The other is when he hears “the noise” and puts his ear to the ground to listen to it. Nobody else can hear the noise. Genius alert.

My next reference was in February 2020. He helped Boris Johnson win the 2019 election – “Get Brexit done” – and stayed on as his lead adviser. One day, he got doorstepped about the HS2 high-speed rail network and said: “The night-time is the right time to fight crime, I can’t think of a rhyme.” My kids laughed. I laughed. Then Covid, his trip to Barnard Castle, garden press conference, leaving Downing Street in November 2020. I was fascinated by then.

I first asked to interview him in January 2020. He was the most powerful person from the north-east, a region whose national presence has nearly been subsumed by “the north”, yet here was someone who knew it and had the ear of the prime minister. I emailed. Nothing. Tried more times. Nothing. Listened to him on podcasts. Read his blog. Sort of. Then, last year, it became more urgent.

In July 2025, he wrote on his blog that he was – once again – working on a plan “for if you take over No 10 – what do you do in the first hour, day, week, quarter to set things on a profoundly different path”. He was on manoeuvres, planning a comeback, despite everything. Nobody was surprised. I messaged again. Nothing. I messaged his wife, Mary Wakefield, an editor at the Spectator. She said she’d pass the message on. In December, as I drove up the A1 with the kids in the back, five messages popped up on my phone:

“Hello andrew”

“It’s Dom Cummings”

“My wife says I shd talk to you cos you wrote a book about [Raoul] Moat”

“Better reason than most”

“What are you doing?”

I want to know what you’re up to Dom.

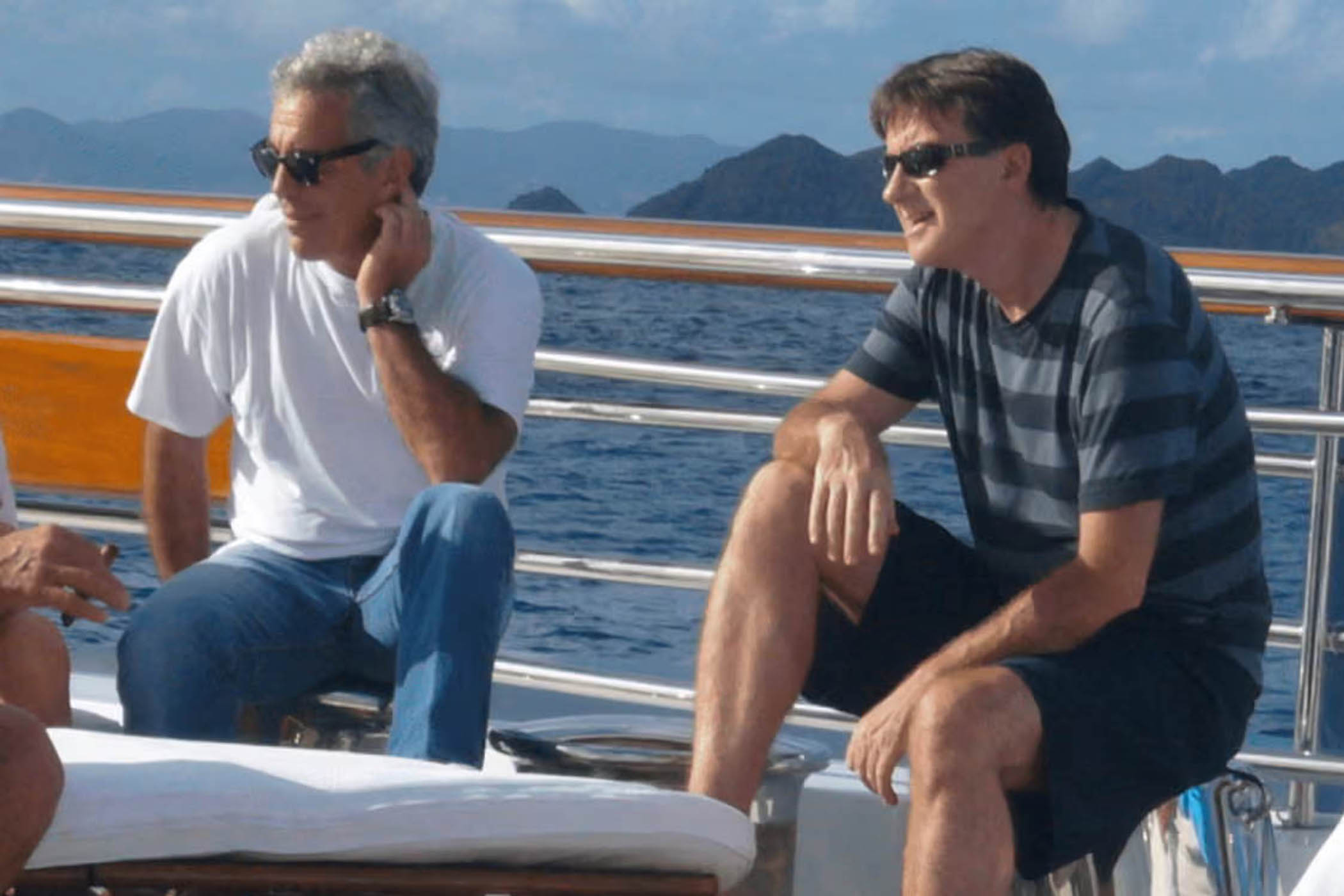

Klute, the three-storey nightclub in Durham where Cummings worked in his youth

I went to Oxford in June last year to see Dom give a talk. What a place Oxford is. I live in a nice suburb of Newcastle with tall trees and big houses, but Oxford is different. Someone cycled past me in a beret. There’s an aura to the students, as if they know their feet will barely touch the floor in life; they’ll glide, doing whatever they want. God, I want my kids to be one of them.

Dom’s talk, organised by the Pharos Foundation, was at the Sheldonian: “The ceremonial home of the University of Oxford.” I assessed the queue. One man had embarrassed himself by turning up in a smart shirt, smart jeans and polished shoes. A doughy man wore a smart shirt paired with goofy trainers, which was more like it. Another man had a Hard Rock Cafe T-shirt, crap shorts, knee-high socks and a bad haircut. I assumed he was a genius.

In the hall, I chatted to a retired accountant. He’d recently caused tension at his local debating club by suggesting they discuss halal meat. Church bells rang as Dom started his speech. He wore a baseball cap and wrinkled T-shirt: “I’ll talk first of all about some of the things that have gone wrong, some of the deeper issues about why I think they’ve gone wrong and a few basics of what we’ve got to do to get ourselves out of this situation.”

Subjects covered included the need to close the Cabinet Office, “the vast cover-up of industrialised mass rape of white English children by Pakistani and Somali gangs” and, to illustrate procurement failures, upgrading the cross-Pennine A66. “I think we’re going through a normal cycle of history,” he said. “Slow rot, elites blind and then fragmenting, sudden crisis, fast collapse and then regime change, and a new elite with new ideas allied with a subset of the people who supply energy and legitimacy take over.” Me and the accountant made notes.

After 45 minutes, Steve Edginton of GB News asked Dom questions on stage about immigration. Afterwards, I heard a man outside say: “He’s obviously an intellectual, but he hasn’t got any solutions to it.” I walked round the corner to Exeter College, where Dom went. His mum’s brother, Sir John Laws, a former lord justice of appeal, went there before him. A barrier blocked non-students from accessing the grassy quadrangle. As I peered through the entrance beside a tourist taking photographs, a young man walked through and said: “VIP”, then turned around and apologised, realising how it sounded.

I asked Dom if him getting into Oxford was a big deal to his parents. “No, I wouldn’t say a big deal.” Did people comment on his north-east accent? “No. I didn’t have … Some people, I think, struggle with that whole thing and, like, change their accent.”

Others double down on being northerners. But not him?

“No, I just … I’ve never seen myself in class terms or anything like that. I just kind of ignored it all.” When I asked if his dad was professional class or working class, he said: “Class in the north is tricky.” Which is true. The terms used elsewhere often don’t fit up here. Politicians get it wrong. Dom was their decoder.

Tell me about Dom playing ping-pong in Russia? “He was clever,” Denis Smyslov told me. “Well, I would say sharp. And it was nice to have, like, a few vodkas with him and talk about philosophy or history. We played table tennis a lot. He was very good. He was better than I was.”

Where did you play?

“I lived in Peredelkino. The writers’ village near Moscow. A nice wooden dacha in the woods.” Dom lived there for a while. “We had a table tennis [table] in front of the house,” said Smyslov. “And we did a lot of parties.”

Dom moved to Russia at the end of 1994, a few months after graduating with a first in ancient and modern history. “A lot of young Brits wanted to do so,” said Smyslov, “and just make themselves in this turmoil of perestroika era. I had a business partner, Gleb, and he just returned from Oxford and knew [the Oxford historian] Norman Stone. I think Dominic asked [Stone] whether he can recommend somebody in Moscow, so Norman Stone gave him Gleb’s name.”

Gleb and Smyslov were starting an asset management company called Global Fund Management. When Dom arrived, the three of them worked in a borrowed room in a bank in Moscow. “We were two Russians and we wanted to manage foreign assets,” Smyslov said, “and so when Dominic appeared [on] our doorstep, it was like God blessing for us because we would have one foreigner, Oxford-educated … he started writing probably weekly investment reports for us.”

At night, they went clubbing. “They were quite wild and were, of course, all controlled by organised crime groups,” said Smyslov. “You had to be careful; don’t interfere, don’t get too drunk and don’t make too much trouble.” Dom was less worried: “Moscow nightclubs seemed much safer, generally speaking, than English nightclubs. English nightclubs are extremely violent and constantly kicking off in various ways. Whereas, in Moscow, people were worried about getting shot, so the environment is somewhat different.”

Benedict Cumberbatch, centre, portraying Dominic Cummings in Brexit: The Uncivil War

Dom spent less than a year at Global Fund Management, then tried to help set up an airline in Samara, about 700 miles (1,100km) east of Moscow. The airline failed and Dom returned to the UK in 1997. In November 2019, a month before the general election, when Dom was the prime minister’s adviser, Labour raised concerns about his time in Russia. Labour MP David Lammy tweeted a link to a news story about it with a comment: “Is Dominic Cummings a Russian Spy? Hidden in plain sight.”

I asked Dom if that bothered him. “It didn’t annoy me, personally, because my life just became such an incredible insane asylum of accusations and the creation of all kinds of stories about me that were completely fake. That was just one more among many which didn’t bother me, but it was obviously very bad generally for the country and for America that this whole hoax took on a life, because it meant you have these political elites just completely delusional about what’s going on and not facing the reality of why they lost against Trump and why they lost the Brexit referendum.”

Lammy is lord chancellor now. The tweet’s still up. I asked the Ministry of Justice press office if he stood by its words. It declined to comment. In 2021, the journalist Lynn Barber asked Dom if he was involved with security services. He replied: “Well if I were, I’d have to say no! But nevertheless, a categorical, ‘no’.” When I asked for a response to Lammy’s accusation, Dom messaged: “Haha, as a good russian spy would say of course im not a russian spy … SHMERT SPIONEM, death to spies.”

“Dominic, of course, was a constant source of pointed, trenchant ideas and suggestions. Sometimes we even asked him for them,” wrote Norton in his book White Elephant: How the North East Said No. You can’t buy it anywhere. The British Library has only one copy, but it won’t loan it to a north-east library. I got a copy sent over from Princeton University.

It tells the story of the North East Says No campaign during the 2004 referendum on whether the region should have its own assembly. Labour wanted to roll these out nationwide. The north-east was the first region to get a vote on it. The Conservatives asked Norton to be the agent for the no campaign. Dom, who’d campaigned against the euro after he came back from Russia, was strategy adviser.

As the proposed assembly was going to be in Durham, Dom suggested Norton speak to his uncle Phil, who became the campaign’s responsible person and director. “We would have been nothing without ‘Napoleon’,” Norton wrote of Phil, “the last to retreat, the first to attack (not always against the enemy).” Dom’s dad, Robert, was financial controller. “A calm, methodical and unhurried man,” wrote Norton.

The third brother, Neil, is described by Norton as a “supporter”. When journalists were invited to watch female students from Durham University throw bundles of fake cash on a bonfire – “Politicians talk. We pay,” was the campaign slogan – it was on Neil’s farm. The no campaign won by 696,519 votes to 197,310. Labour abandoned its regional assemblies plan.

Dom had proven his political skills. Two days before the north-east referendum victory, Norton described watching the US presidential election – George W Bush versus John Kerry – with Dom at Phil’s house. “It took a deal of channel hopping to decide which version to watch (although I believe the result was the same on all of them) – Dominic had the remote control.”

One of Dom’s early influences was War Room, a documentary about Bill Clinton’s winning 1992 US presidential election campaign. “I can’t remember much about what it taught me,” Dom says now, “apart from a) the famous sign and the importance of clarity and simplicity about the core story; and b) ‘speed kills’… Both things I understood much better after studying Boyd.”

The sign was a whiteboard with the campaign “rules” on it: “Change vs more of the same. The economy, stupid. Don’t forget healthcare.” Speed kills meant acting fast. In one scene, after it’s clear they’ve won, Clinton’s lead strategist, James Carville, a quirky man from the American south, is shown in a cap and T-shirt that reads: “Speed killed … Bush”.

People are in a cycle of: ‘Both the old parties have screwed us. Should we roll the dice on Farage?’

People are in a cycle of: ‘Both the old parties have screwed us. Should we roll the dice on Farage?’

Boyd is John Boyd, an American fighter pilot and military strategist described by his biographer, Robert Coram, as “dishevelled”, sometimes “abrasive”, willing to make enemies, but clever and effective. “People in the building did not know if Boyd was a genius or a wild man,” wrote Coram. In one scene, Boyd plots data in his head, confounding a peer who “could not hear the music”.

Having watched War Room and read Coram’s book, I had this cynical thought: there are lots of clever, well-read people, but behaving like Boyd and Carville helps them stand out. Did Dom borrow that behaviour? “No, I wouldn’t say Carville influenced me,” he said. “Not in any significant way. Definitely reading John Boyd’s presentations influenced me.”

It’s just that, you dress differently?

“Dress differently, you say?”

Like, casual. Is that influenced by Boyd?

“No,” he said. “Influenced by a mix of laziness but also Silicon Valley.” He told me about Andy Grove, a former chief executive of Intel, who used clothing to foster a “culture of honesty”.

“Part of the reason I dressed like that at No 10,” said Dom, “was to try and bring something of that there; to try and say: ‘This has got to be a different kind of culture in which younger people are free to say: We think you senior people are fucking things up.’”

We spoke on the phone in January. Phone interviews aren’t great. Too much racing to get something, anything on record before they hang up. Not that Dom was rude. He was polite, generous, still talking even when I delayed him on his way to pick up his kid. As he got closer to his destination, I moved on to his plan for whoever becomes prime minister to carry out his proposed reforms. Has he written it? “Yes.”

Has he shared it with anyone?

“I mean, I talk to all sorts of people about all sorts of different plans. And all sorts of different people work on different things that they think are important for the future. So, I mean, it’s not just me. There’s lots of people thinking about what the hell could be done if we can get rid of the old system.”

What’s in it?

“I mean, I’ve talked a lot of shit, right, in the last few years about what should be done. So, at the moment, I wouldn’t want to say anything other than what I’ve said publicly. I’ve said a lot publicly and I’ve said a lot on my blog, but for the moment, I don’t want to go into any other details about the future because these things are all sensitive.”

On the Telegraph’s podcast he said he talked to Nigel Farage, the leader of Reform UK, about “the Cabinet Office and how power really works” over dinner in December 2024. Could Farage implement his plan?

“No one knows, right? At the moment, Farage keeps telling people he’s gonna recruit serious people and prepare for government in a serious way. Obviously, so far, it hasn’t happened, but he tells people that, after May, it’s going to happen.”

Is Robert Jenrick not serious?

“What I mean by preparing seriously is recruiting serious talent from outside politics; people who’ve successfully done things, people who’ve built businesses, people from the army, people from education, people who actually understand things and know what they’re talking about and can build.

A billboard posted in London by campaign group Led By Donkeys in June 2020

“So, from my perspective, when I say, ‘recruit serious talent’, that doesn’t mean shuffling around people who’ve been MPs before. I don’t mean by that, obviously, that all of them are rubbish, but if you’re serious about recruiting talent, then the vast majority of it obviously has to be from outside parliament. Because approximately all serious talent in the country is outside parliament.”

In October, Dom appeared at an event organised by Looking for Growth (LFG), a growing campaign group he’s helped, with more than 20 chapters across Britain. “End Decline. Save Britain,” the flyer said. Speakers included MPs from various parties and entrepreneur Matt Clifford. It was at the Indigo theatre at the O2 in London. When Dom mentioned procurement reform, the crowd cheered. He told them if Farage can’t “tap into” the political fragmentation, “someone else will create something to do that”.

That month, Dom also ran focus groups. Were they for the new party that he talked about a while ago?

“I don’t want to say much about it,” he said. “I’ve done them for my own interest, but also to try to tell various people who are involved with politics or thinking about getting involved with politics: ‘It would be helpful for you if you base what you’re thinking about on the reality of what voters think rather than what the media says they think.’”

What did the focus groups reveal?

“People are in a cycle of: ‘Both the old parties have screwed us and are rubbish. We can’t vote for them again. We want change and keep voting for change, but no one will actually change anything. Should we roll the dice on Farage? Well, he might fuck it up as well, but on the other hand, what have we got to lose? We know for sure it’s pointless voting Tory or Labour. So we might as well, but, yeah, it’ll probably go tits up if we vote for Farage. What else can we do? Well, the other thing we can do is leave [the country].’ That cycle of discussion is one you hear a lot all around the country, much more so than the past. People are much more depressed and angry than they ever have been in living memory.”

As I typed up that quote I had this feeling of: “We’re all trying to find the guy who did this.” But that’s not quite fair. Dom should take some blame for the mess we’re in, but we’re not where he wants to be either.

“The remainers are not happy that Brexit happened,” he said, “and people like me who voted for Brexit are not happy because we wanted the country to go in a different direction.”

Hence, he wants to take back control (again) by getting a prime minister in power who’s willing to do the radical, such as close the Cabinet Office, repeal the Human Rights Act, withdraw from the European convention on human rights, reform education …

By 2029, it may well be one of the options on the table as we decide which direction to go in.

“The old parties are already dead,” Dom said in Oxford. “It’s like one of those Japanese movies where a samurai whips their heads off, but they haven’t quite realised yet.” Kemi Badenoch, nobly waving off the lifeboats. Keir Starmer deeply regretting his own speeches and announcing policies none of us expect to happen. A carefully folded napkin in No 10 wouldn’t be much different. There’s talk of replacing Starmer with Ed Miliband, a man the country has already rejected. Meanwhile, Reform looms.

Round and round on the gloom loop we go, politicians offering another ride, but none indicating they have the party, policies and personality to lead the country to a better future. So some people listen to Dom. “LFG to the max,” he said at the O2: either Looking for Growth or “Let’s fucking go” – take your pick. A special forces anti-regulation operation. He’s a man with a plan – always – if only he could find the right person to implement it.

Photographs by Landmark Media/Alamy, AFP/Getty Images