During his keynote address at London Tech Week on 9 June, technology failed Keir Starmer. As the UK prime minister took to the stage in front of an audience of hundreds of tech industry insiders, his autocue froze, forcing him to riff for two minutes about the “transformative” nature of AI.

Still, his message was clear: this government is going all-in on artificial intelligence. After his aide handed him an analogue printed speech, Starmer promised that, thanks to AI, “we can put money in your pocket, we can create wealth in your community, we can create good jobs, vastly improve our public services, and build a better future for your children”.

Starmer was later joined on stage by Jensen Huang, the founder of chipmaking giant Nvidia, where they announced a £1bn investment in AI infrastructure in the UK.

Two days later, across the channel at VivaTech – a competing event – the same story was repeated. Also flanked by Jensen Huang, President Emmanuel Macron hailed the promises of AI and announced a multi-billion dollar partnership between Nvidia and France’s leading AI company, Mistral. Optimists say this is a chance for European business to break out of stagnancy. Sceptics say Macron and Starmer are overly reliant on US tech firms.

I attended both events, which were intended to showcase the cutting edge of technology development, but mostly focused on AI – with a touch of quantum computing. Among the many booths, I ate a macaron while having my brain scanned to measure my levels of “satisfaction” (a disappointing 22%); had a robot hand me an object; but mostly I watched hours of panels where industry leaders shared their predictions for the future of European tech. Here are my top five takeaways:

The era of agentic AI is upon us

If there was one buzzword that dominated both events, it was “agents” – AI models such as ChatGPT that can be refined to help with work tasks, from drafting emails to writing code. Companies from Amazon to the marketing giant WPP say they are already rolling them out to support their workforces, while consultancies and outsourcing firms are lining up to sell solutions for integrating them into the workplace.

Euro Beinat, global head of AI and data science at the investment group Prosus, says 15,000 employees already use the company’s AI agent tools every day. Mainly used in sales and engineering, those agents even come with their own job descriptions.

Beinat tells me he sees each one as a “junior intern”, because these tools can be buggy, slow, and sometimes make things up. He later told a panel that rolling them out was like taking a big Ferrari engine, putting it in a Fiat and driving on a road full of bends with no guardrails. Still, he thinks the mistakes won’t be “lethal”, and tells me he is “very bullish” about the role that AI agents can play in boosting business. He says Prosus Group is already seeing returns of two to five times on its annual $100m AI investment.

Related articles:

While the pressure is mounting for businesses to move quickly or risk missing the opportunities that come with AI, exclusive data from the Boston Consulting Group shared with The Observer suggests that haste comes with its own dangers. Although 43% of UK businesses are prioritising investment in agentic AI, only 51% of those leaders could clearly define it. Rolling out a technology you don’t understand could be a waste of time and resources.

The data also showed that junior employees are less comfortable about the rollout of AI than their leaders. That may be explained by their concerns that AI could lead to entry-level job losses – a topic notably avoided by most tech week speakers.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Starmer with Nvidia boss Jensen Huang at London Tech Week.

Chatbots aren’t the only good use of AI

Since the launch of the viral chatbot ChatGPT in November 2022, large language models – the technology underpinning these bots – have dominated the conversation. Jean Innes, CEO of the Alan Turing Institute, told a panel these models are “amazing, but they’re one type of AI”. At times, they overshadow other exciting developments.

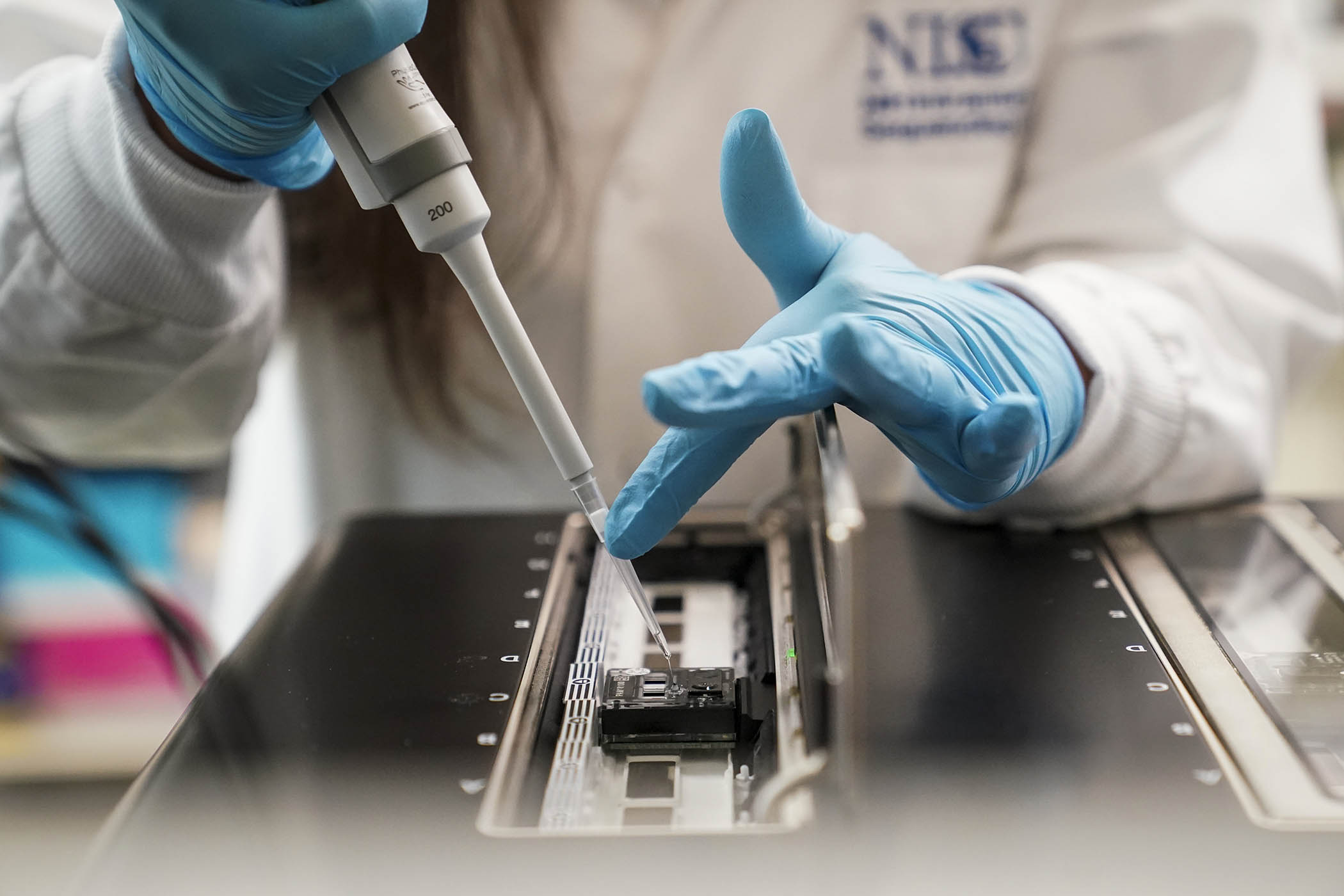

Last month, for example, the institute announced that it had created more than 3,800 anatomically accurate “digital hearts”, using patient data and ECG readings from the UK Biobank. Using a technique called “digital twins”, the hearts simulate the behaviour of their human counterparts, including blood flow and pumping. They’re then used to explore how age, sex and lifestyle factors influence heart disease, as well as investigating heart functions that can be difficult to trace on humans.

These technologies are costly, but they might help us better understand how disease works, and move towards personalised healthcare. The Turing Institute is using digital twins to tackle a range of problems, including assisting air traffic controllers.

Personalised health tech is on the rise

From the unfortunately-named Emobot, a French startup tool that is meant to detect depression and other mental health disorders, to at-home stroke detection tools, there is a boom in companies that want to help users monitor their health at home. Buddyo – a medical device that debuted at VivaTech, developed by the startup BodyO – is a 6.5kg robot that can check your blood pressure, oxygen levels and about 20 other health metrics. It also has a screen with an AI assistant that can chat to you about your medical questions. It costs a reported 50€ a month, or 2000€ upfront.

The global medtech industry is already worth half a trillion dollars and it’s set to keep growing, accelerated by the pandemic and overburdened national health systems. The regulation of these devices – and the ability to integrate the data they produce into the traditional healthcare system – is likely to present challenges.

Taking back control of your data

Sir Tim Berners-Lee founded the world wide web in 1989 while working at Cern. His idealistic vision, he tells The Observer, was to make information and opportunities accessible to all. He did go some way to achieving that: “There’s a huge amount of the web which is useful, which is creative, constructive, and collaborative,” he says. It changed the world, after all.

But he worries that people are too often becoming trapped by “ addictive systems that rely on building a profile of you”, selling personalised data to advertisers. It’s a model of the web that he calls “dystopian”.

Now Berners-Lee says he wants to “empower” users of the internet once again. Through a new venture, Inrupt, he and his business partner John Bruce are providing users with “data wallets”, giving them visibility over the data they own and how people – such as governments and healthcare agencies – interact with it. “ It is all about fulfilling my original dream,” Berners-Lee says.

The platform is not perfect: so-called decentralised platforms can be complex to use and laggy, and some people worry they might introduce security risks. But Inrupt has successfully trialled its product with the government of Flanders, Belgium, and it recently announced a deal with Visa.

Among its dream clients are more governments and healthcare providers, but convincing them has proved slow and bureaucratic. Bruce says the UK government “gets it”, but has other priorities throughout its four years in office. “You need to take a long view on most of these things,” he says. “That unfortunately flies against what most politicians have to do”.

Sexism is alive and well

The businesswoman and House of Lords member Martha Lane Fox told London Tech Week that “we are actually going backwards” when it comes to women in the workforce. She quipped that “there are more women in the House of Lords than in tech”.

According to a report by the World Bank, women make up less than a third of the world’s tech workforce, and a measly 2% of venture capital funding goes towards companies with at least one female founder. Women currently make up 31% of the Lords – and that’s after Keir Starmer appointed more women than any other prime minister.

Meanwhile, tech entreprenuer Davina Schonle was turned away from London Tech Week for carrying her young baby.

Debbie Wosskow, co-chair of the Invest in Women Taskforce, said: “If a founder is turned away from a space where she was due to meet suppliers for her own business, what does that say about the potential for female founders to secure investment? It’s a tired old scenario and a tired old system and doesn’t do anything to dispel the ‘tech bros’ persona.”

That all might go some way to explaining the female AI assistants dominating both Paris and London exposition booths. I met a blonde, big-breasted AI assistant whose tagline said she could be “assistant, your fashion adviser, your performance. She is your personal AI agent in the new AI time”. Elsewhere, a friendly cartoon standing with her hands on her hips offered to help me with my train bookings, and an elderly female doctor assisted with my health queries. At least she was a woman in Stem.

Photographs by Ray Tang/Getty Images and Carl Court/Pool via AP