Is there life on Mars? Nasa and its international research team tried hard not to give a straight answer to David Bowie’s question last week, despite the most intriguing development in Martian exploration since humans first sent machines to the red planet.

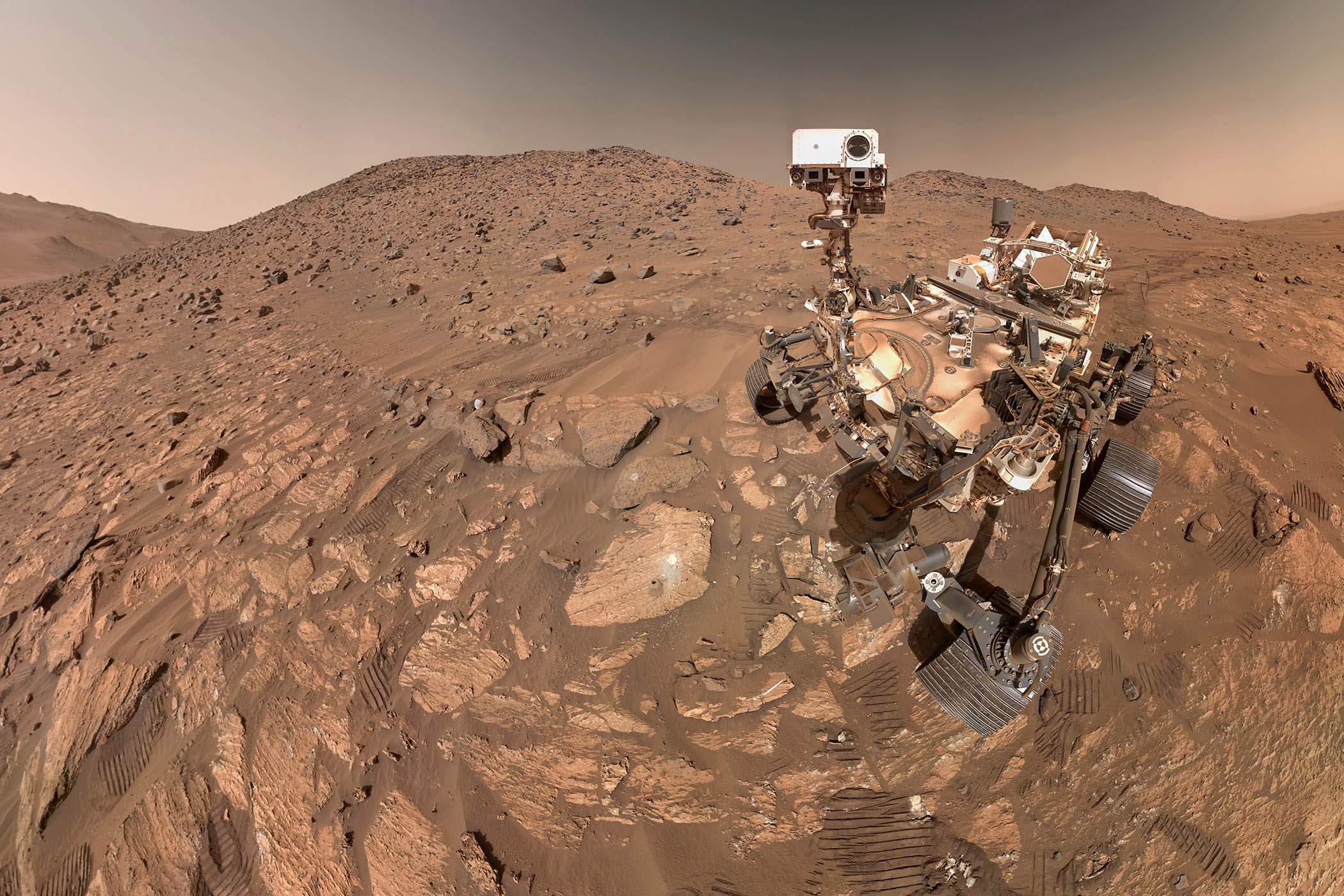

Its caution is partly scientific. Images transmitted by the Perseverance rover reveal spots on rock that show all the signs of being caused by microbes. This “potential biosignature” provoked much excitement among astrobiologists; it was also a starting gun for labs around the world to try to demonstrate these spots could have been created by geological or other processes.

The question that scientists are really asking is less lyrical and almost philosophical: can we ever really know if there was life on Mars?

The idea of alien lifeforms extends back at least to Lucian of Samosata, whose 2nd-century proto-novel, A True Story, imagined a war between extraterrestrial armies of the sun and the moon. Mars is a better place to look. There is much more evidence it once had Earth-like qualities, with an atmosphere that had a water cycle, including lakes and river deltas.

But the Earth has a global magnetic field, whereas the one around Mars disappeared, ending its protection from the harsh solar wind that stripped away much of the atmosphere.

“It’s like a mummified Earth,” said Joel Hurowitz, associate professor at Stony Brook University in New York and a member of the Perseverance team. “Life on our planet was nothing but microbes for the first 3bn years of its history.”

The Earth’s tectonic plates have destroyed most of that evidence, but Mars is desiccated, so if it had microbes, evidence of them might have been preserved to help us understand the origins of life. (If you want to know what Mars looks like, head to the Torridon mountains in north-west Scotland to see 2bn-year-old rocks).

The Perseverance has been searching in Jezero crater, inching its way across this former river delta and lake at 300 metres a day, scanning rocks and analysing the landscape. Since the rover landed four years ago, scientists have directed it to drill 30 samples of rock, stored in test-tube-sized cannisters, in the hope that they can be returned to Earth.

Related articles:

Analysis by the rover’s onboard instruments shows that the sample from Jezero is of riverbed sediment and clay – exactly the sort of place where microbes might have accumulated, and where the spot-like features were found, according to Prof Sanjeev Gupta, a planetary scientist at Imperial College London and also one of the Perseverance team.

“It’s really about the samples coming back, essentially,” Gupta said. “Unless we saw a fossil in the rocks, it was never going to be a slam-dunk ‘We have life here.’ We need to bring it back to Earth laboratories.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Scientists could then use full-scale instruments to examine its chemical composition, isotope ratios (the variation in elements such as iron) and morphology (to see whether any shapes inside it could have been caused by microbes).

Cuts by Donald Trump to Nasa’s budget mean there is no timetable to bring the samples back, although the space agency’s acting head, Sean Duffy, said he was “pretty confident” it could be done. Yet even with the samples, would that really be enough to be sure?

“If we just probe morphology, or just chemical composition, or isotope ratios, there’s a huge grey line,” said Pamela Knoll, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Edinburgh. She has been trying to establish a baseline for how rocks look in places where there is an absence of life. “There's this huge grey region overlapping between what is biological and what happens in the absence of life.”

It is hard to find a place on Earth where life does not exist. Astronauts discovered fungus growing on the outside of the Mir space station in 1988, somehow surviving the vacuum and fierce solar radiation.

The Perseverance scientists have to follow a strict protocol to ensure the rover does not come into contact with any water and accidentally colonise the planet with a contaminant from Earth.

“Fungus is so annoying,” Knoll said. “As an experimentalist [examining the absence of life], you think you have found conditions where nothing would grow, and somehow it finds a way in.

“If you go anywhere on Earth, it’s almost impossible to find no life. Then on Mars, we are extensively searching, and we’ve found what is now a potential biosignature.”

If Nasa can retrieve the samples, we will edge closer to understanding the origins of life on Earth and whether life may exist beyond its atmosphere. But even if there is no definitive answer, humans are unlikely to give up their millennia-long search.

Photograph by NASA/AP