Illustration by Andy Bunday

Last September, Jared Isaacman emerged from a SpaceX Dragon capsule and peered down at Earth. In doing so, he made history, becoming the first person to perform a commercial space walk. The feat cemented his position in the vanguard of the new space age, led by boundary-pushing billionaires and nimble private ventures rather than vast government agencies.

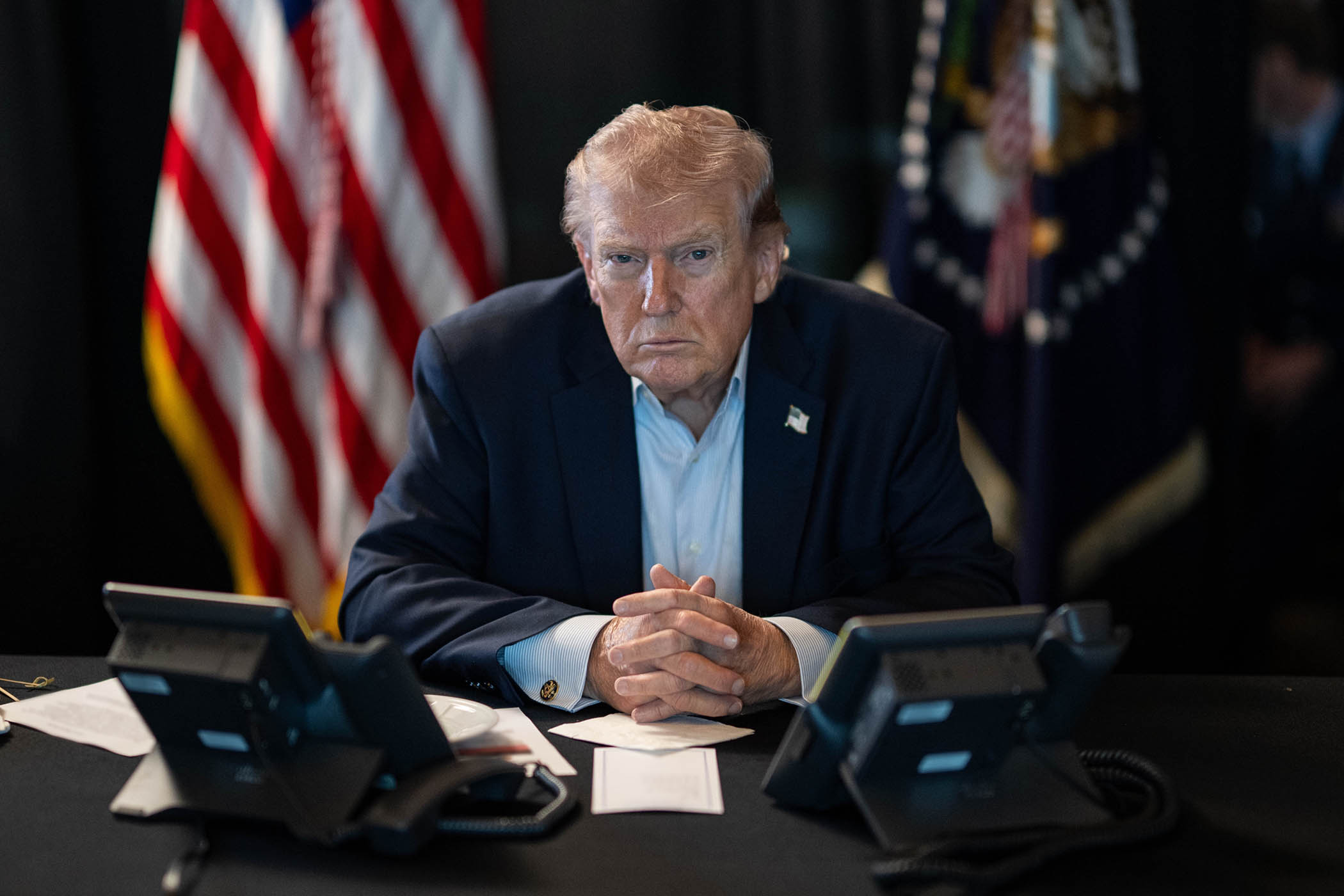

A few weeks later Donald Trump picked Isaacman to run Nasa, a move that sent a ripple of excitement through the space community.

“It seemed like an almost inspirational choice, a really good fit for this new era of commercially enabled space travel,” said Simeon Barber from the Open University, who builds lunar landing craft. “He had enough money to do whatever he wanted with his life, and he chose to go into space. He’s genuinely got a passion, and that counts for a lot.”

Then, in May, Trump abruptly changed his mind and cancelled Isaacman’s nomination, days before the Senate was due to vote on it. Observers suspected this was related to the president’s spat with Elon Musk. After Nasa itself, Isaacman is arguably the best customer of his company SpaceX.

In a second twist, Trump re-nominated Isaacman earlier this month as relations with Musk thawed. On Wednesday the Senate will grill Isaacman on his plans for the agency – plans that remain, for now, in the realm of science fiction. The billionaire is a supporter of mass space travel and sending humans to Mars, ambitions closely aligned with those of Musk. He has lamented the fact that only about 600 people have left Earth’s atmosphere. “We want it to be 600,000… I drank the Kool-Aid in terms of the grand ambitions for humankind being a multi-planet species,” he said in 2021. “I think that we all want to live in a Star Wars, Star Trek world where people are jumping in their spacecraft.”

A thrill-seeking billionaire who flies fighter jets in his spare time is an unconventional pick to lead Nasa

A thrill-seeking billionaire who flies fighter jets in his spare time is an unconventional pick to lead Nasa

Isaacman has also spoken of “a thriving space economy” as an inevitability that will “create opportunities for countless people to live and work in space”. At the helm of Nasa he wants to “usher in an era where humanity becomes a true spacefaring civilisation”.

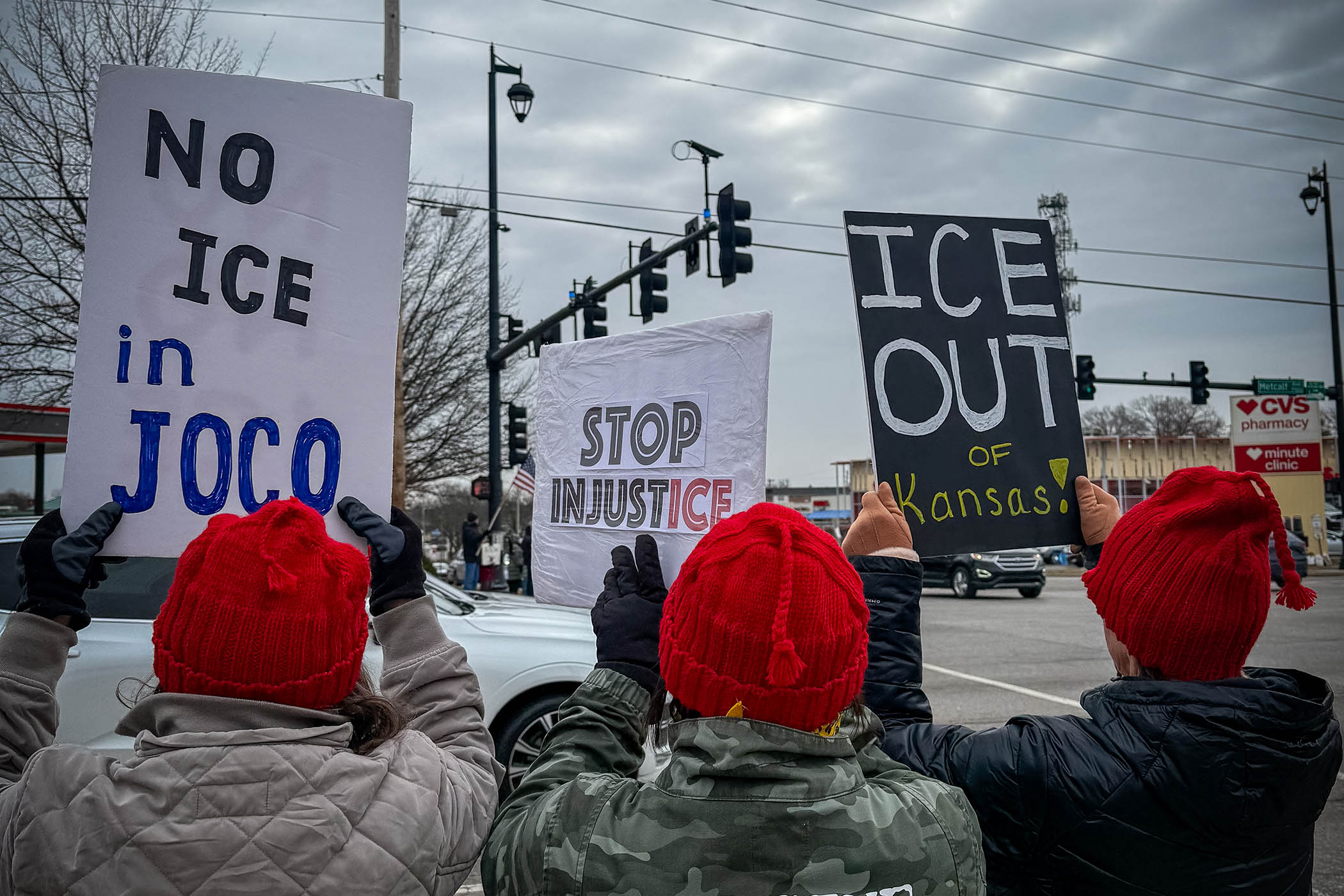

But his first priority will be more down-to-earth: reviving the spirits of an embattled government department that is low on morale. Trump is threatening Nasa with deep cuts that would slash its science budget in half and reduce its staff by a third. Thousands have already left. Meanwhile, technical delays to its Artemis lunar programme mean the US risks losing the race to return to the moon to China, which aims to send an astronaut there by 2030. Nasa had planned to go back by 2024 but is now targeting 2027.

“Isaacman’s first task will be to heal the agency, because it’s been under such pressure over the last year, with all the job losses and threats to close research centres that have done such amazing things,” said Barber. “A lot of people I know who have worked at Nasa are just in shock at the moment.”

A handsome, thrill-seeking billionaire who flies fighter jets in his spare time, Isaacman is seen as an unconventional pick to lead Nasa. Born and raised in New Jersey – he still lives in the Garden State – he dropped out of Ridge High School at the age of 15 to found Shift4 Payments, the finance firm that made him his estimated $1.3bn fortune. (He called it United Bank Card at first, because he thought it sounded like an established company.) He later co-founded Draken International, which owns a fleet of military aircraft and helps the US Air Force with training. He has two children with his wife, Monica. They married in 2011, having first met in junior high.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Sean O’Keefe, who ran Nasa from 2001 to 2004, thinks Isaacman has the right stuff, arguing it is a myth that Nasa administrators “all come from some monolithic, similar background of science or technology or engineering”.

“The job is a leadership role, where your task is to motivate people from wide-ranging, different disciplines to come together to define the problem as the same and then go about trying to solve it through multiple avenues,” he said. “Everything I’ve heard about him certainly suggests that he’s got a lot of talent and capability to make him the ideal person.”

Isaacman has made two trips with SpaceX. In 2021, he completed the first all-civilian orbit of Earth, paying a rumoured $200m to charter one of Musk’s spacecraft for three days. Among the four-person crew was a bone cancer survivor and a US Air Force veteran who won a raffle out of 72,000 applicants and raised $100m for St Jude, a children’s cancer research hospital. Isaacman also donated $100m of his own money.

“He’s your young tech billionaire who likes to give back, that’s the sort of warm general impression you get,” said Keith Cowing, who runs the website Nasa Watch. “He’s a nice guy and made sure his crew was half women, included someone with cancer and he’s humble for all he’s accomplished.”

But there are concerns that Isaacman’s passion for human space exploration may lead him to neglect Nasa’s research programmes, some of which monitor glacier melts, sea levels and global temperatures. These are firmly in the sights of Trump, who has called climate change a “con job”.

In a confidential memo, leaked to Politico in November, Isaacman set out his plan to radically overhaul Nasa by outsourcing more of its work to the private sector and treating it like a company. He also proposed ending Nasa’s climate science work and leaving it “for academia to determine”. This has ruffled a few feathers, although it’s not clear if Isaacman was calling for Nasa to stop collecting climate data, or if he intends merely to outsource its analysis to academics. After all, Isaacman has previously criticised the agency’s costly procurement process for its new lunar landers, saying it came “at the expense of dozens of scientific programmes”.

A big target of his is the Space Launch System (SLS), a rocket designed to send people to the moon that he has denounced as “outrageously expensive”. It is billions over budget and years behind schedule, and will cost an initial $4bn to launch, partly because it is disposable. By contrast, Musk’s Starship costs about $100m per launch and can be reused, although it is also beset by technical delays. Another worry is a potential conflict of interest, given Isaacman’s close relationship with Musk. However, Nasa already relies on SpaceX to ferry astronauts to the International Space Station, an arrangement that costs billions of dollars.

Barber says it makes sense to deepen Nasa’s collaboration with the private sector. “Apollo was the most remarkable technological achievement, but it was so phenomenally expensive that it had to be stopped. Things need to be done more sustainably. The challenge for Nasa is how to adapt to work with these new companies and to find its own role, which is going to be very different to how it was in the past.”

O’Keefe points out that Nasa has always collaborated with the private sector and believes the current debates about the agency detract from its storied history. “It’s getting pushed around a fair bit today, but it’s not gone,” he said. “And it can be resurrected by a guy like Isaacman’s capacity. In many ways, this a very, very exciting time for space exploration.”

Jared Isaacman

Born New Jersey

Alma mater Embry–Riddle Aeronautical University

Work Entrepreneur, astronaut

Family Married, two children