A fathom (noun) is 1.8 metres (6ft) of water. To fathom (verb) is to understand a problem after much thought.

It was a woman who first mapped out the Atlantic. Marie Tharp was an oceanographer in the 1950s. Of all the waters Tharp plotted, the Atlantic remained her favourite. “It’s such a nice symmetrical ocean,” she told the New York Times in 1991. “I felt sorry for the people who had to do the Pacific – it was so much more complicated.” Tharp was an explorer as much as she was a scientist. She mapped the seafloor out by hand. Without ever travelling to her destination, she got there first.

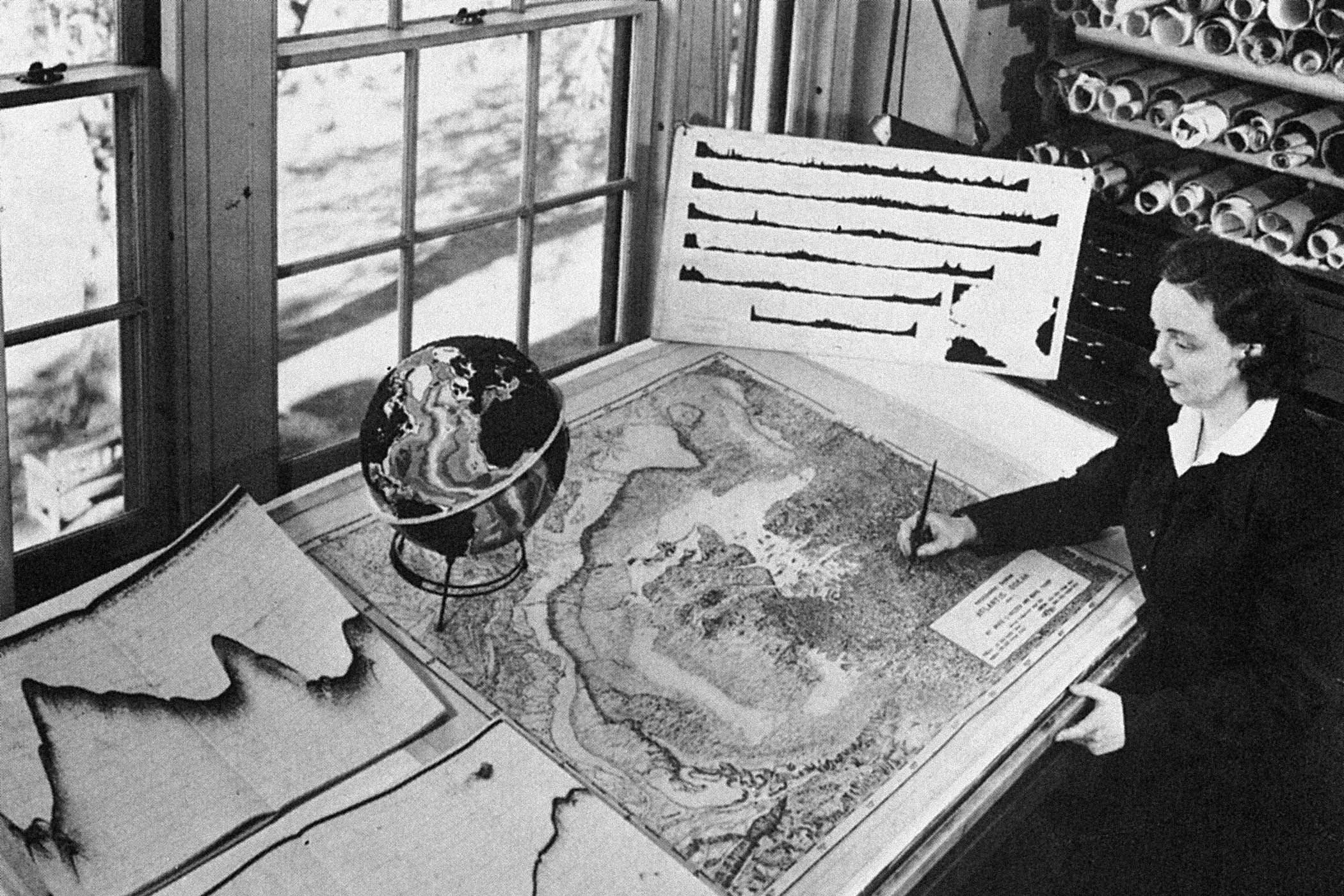

Tharp’s early work was driven by data from small boats sailing back and forth across the ocean, taking echo soundings and feeding the numbers back to her office in the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University, where she laid them out like beads in rows to see what they could tell her. They told her a great deal. The numbers made a topographic record of the ocean floor in two dimensions.

Sound travels faster in water than in air. A sonar ping can register a point on the sea floor as a single unit of abyssal depth, and then another ... and then a whole lot more. Reading the numbers off at each location, Tharp traced the seabed out in strands from one side to the other in sweeping avenues, plotting its inclines, peaks and drops. Out of this laborious process, she joined the dots to make a set of ocean profiles.

Porto to Martha’s Vineyard was one long sonar sliver. Dakar to the Lesser Antilles a fluid single span. Compiling all the profile data made a map. First a chain of mountains materialised, and then inside that range, a valley, followed by trenches, gullies, rifts and plains, plateaus. Here was a landscape never seen before.

Small boats. Big ocean. The early work was slow. Echo sounders were linked to a ship’s electric power and any power failure could interrupt the signal to leave a gap. Where there were gaps, there was hypothesis. One hypothesis could span many nautical miles.

The history of maps is full of blanks and what do we like to do with blankness? Fill it in. Artists turned centuries of ignorance to their advantage through ornament, embellishment and sheer invention. The sea throws up so many things to be imagined ... how to resist? A great white whale, a plague ship, a sea serpent, a long-imagined isle, a siren opening her mouth to sing. For Tharp, imagining was not an option. The cartographers at Columbia couldn’t make it up. Where there was nothing, there had to be something. On Earth, there’s always something. Mare incognitum. No data. Only sea.

There were few females doing the work back then. The navy did not hold with women on boats – they were thought to bring bad luck to ships so weren’t allowed. Pearl Harbor was the reason women got a foot in the door and Tharp didn’t get to sea at all until the 1960s. She stayed on land, working for years with her colleague Bruce Heezen; he on the research ship Atlantis and she in the office with her maps. Slowly, in solid, steady partnership, they traced the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, Tharp taking Heezen’s soundings, plotting, drafting and redrafting as the technology improved and more accurate numbers came in. It was a young science, all to play for.

Tharp had a systems brain in the new dawn of systems technology. She fingered the seafloor out in darkness, working the intervals between number and three-dimensional form to generate the seabed sight unseen through data, guesswork, guided hunch and vast reserves of knowledge. Soundings without the ability to interpret them are just numbers on a chart. Like the early observers of far galaxies, Tharp knew where, and how, to pay attention.

The key lay often in the anomalies; noting down differences in scale, similarities in pattern and chasing down those thrice-checked, congruent, magic points where all the numbers met and all the dots aligned like stars. An astronomer can look at a planet and make assumptions based on existing data and knowledge of other, similar planets. The astronomer has a telescope, at least. Tharp had no such tools and no such data. The undersea was the underbelly of the Earth. It was a tombstone environment, way out of sight.

The first Tharp-Heezen maps were contour ones, but slowly they worked out how to transcribe the lines into pictures, enlisting the help of artists to flesh them out in three-dimensional form. This is what drawing does: it redescribes the world so we can see it differently. To understand how the land lies, sometimes you have to see it from a distance. Her maps were many metres long. In a photograph of Tharp from her time at Columbia, they span the room. She sits among them as they slide across the desk in giant sheets.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Early research was driven by military and corporate interests. Maps of the ocean floor in the 1950s were classified and not for public use. A physiographic map describes the terrain as if seen from the air. It brings the invisible to light. Here was a live source that could be published. The ocean floor could be imagined and once imagined, explored. Once explored, it could be seen.

The Tharp-Heezen project, Physiographic Diagram of the North Atlantic Ocean, ink on paper, still holds much of its power. In parts, it’s Middle-earth. You think to look for fires and forests, castles and goblin hordes across a vast plain pocked with volcanoes and gigantic valleys, scored down the middle by a chain of mountains unrecognisable as any mountain range on earth. Seen at close hand, it’s fantasy. You could be anywhere. The surface of the moon and the seafloor seem much the same. Land frames the sea on either side like brackets. The blotchy clump that constitutes Newfoundland curls like a comma at the edge. The tip of Cornwall stubs its toe top right. The map is printed in Admiralty colours, clean and plain. Water is designated blue, land bleached yellow ochre, and where a seamount breaks the waves, the colour tips as one state shifts into another, wet to dry, to make, like a miracle, an island.

Yellow dots, hard to pick out, scatter the mid-Atlantic waters. Islands are often fairly young. They are ephemeral. Formed by volcanoes pushing up against the weight of water pushing down, they bear the wounds of their adventures. The energy required to make any moves at all in these conditions is cataclysmic. Rocks lie where they fall and, as with any distant planet, the ground is deserving of intensive study. The Canaries are a set of active stalagmites. Small blocks of text are orphaned on the surface, all at sea.

And much like Middle-earth too, the deep was a contested world. Most geophysicists of the time were fixists who thought that land, being rock, the fundament on which we live, was structurally static. Tharp was a pioneer, a drifter. She knew that land was mobile, volatile. She was convinced of the existence of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge but had to work to persuade Heezen. Girl talk, he called it first of all. Girl talk.

But the numbers kept on coming. They pointed to a gap, a rift, a great valley in the middle of the sea. Back then you could be fired for being a drifter and the resulting academic feud got Tharp, not Heezen, sacked. She was the softer target. Withdrawal of support forced them to take the work elsewhere, outside the institution. Tharp took it home with her. The North Atlantic was mapped from a living room in South Nyack, New York.

Many things followed the publication of the map: Bell cables, the developing science of tectonophysics, marine exploration, tsunami early warning systems ... Tectonic plates are thought to move at a rate of 4cm a year. Since 1957, when the Atlantic physiographic diagram was first published, that’s more than two and a half metres at the bottom of the sea and widening.

Tharp does not figure in any Garland encyclopedias. Alexander Graham Bell is there and Jacques Cousteau, the film-maker and oceanographer who set out first to prove her wrong, then realised she was right. Tharp remained a footnote, her name and reputation growing – slowly – at pace with continental creep, until in 1997 she was named one of the four greatest 20th-century cartographers by the Library of Congress.

They used to say that more people have visited the moon than the bottom of the sea – one of those sweeping statements that seems to point to a deeper truth, but hard to work out exactly what. For Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench, at nearly seven miles (11km) down, it’s now 27 and rising year on year, though no one, of course, has walked there. Twenty-four have travelled to the moon so far, but only 12 have stood on it and, from there, turned to look back at us.

Tharp, the cartographer of the Atlantic Ocean, outlived her colleague Heezen by many years and kept on working. Nine years after her death, she got her recognition. This time, it was a true and proper accolade, an honour very far away, befittingly out of reach. Tharp is a crater on the moon.

What Did the Deep Sea Say? by Marion Coutts is published by Fern Press (£20). Order a copy at observershop.co.uk for £18. Delivery charges may apply

Photographs by Historical Picture Archive/Alamy, Marion Coutts