Photography by Kieran Dodds for The Observer

The three stands of the Falkirk Stadium are starting to fill, though not with any particular urgency. The temperature dropped noticeably overnight, bringing with it the first real bite of winter. It is not a day for soaking up the atmosphere. Fans drift to their seats, huddled against the cold, clutching steaming cups of tea or molten wares acquired from the Pie Sports kiosk.

The far corner of the Kevin McAllister Stand, though, is a hive of activity. Half a dozen fans have been scurrying up and down the stairs for almost an hour, disappearing briefly inside and then emerging once again, each time bearing a different piece of equipment: a drum, a roll of midnight blue material, a flagpole, a megaphone.

Once they are delivered, others start to piece it all together. A man in a bucket hat wrestles with the flagpoles, screwing them together as the loose material whips in the breeze. Two more, their scarves worn as sashes, carefully affix the banners to a makeshift framework at the front of the stand, operating on the principle that you can never have too much gaffa tape.

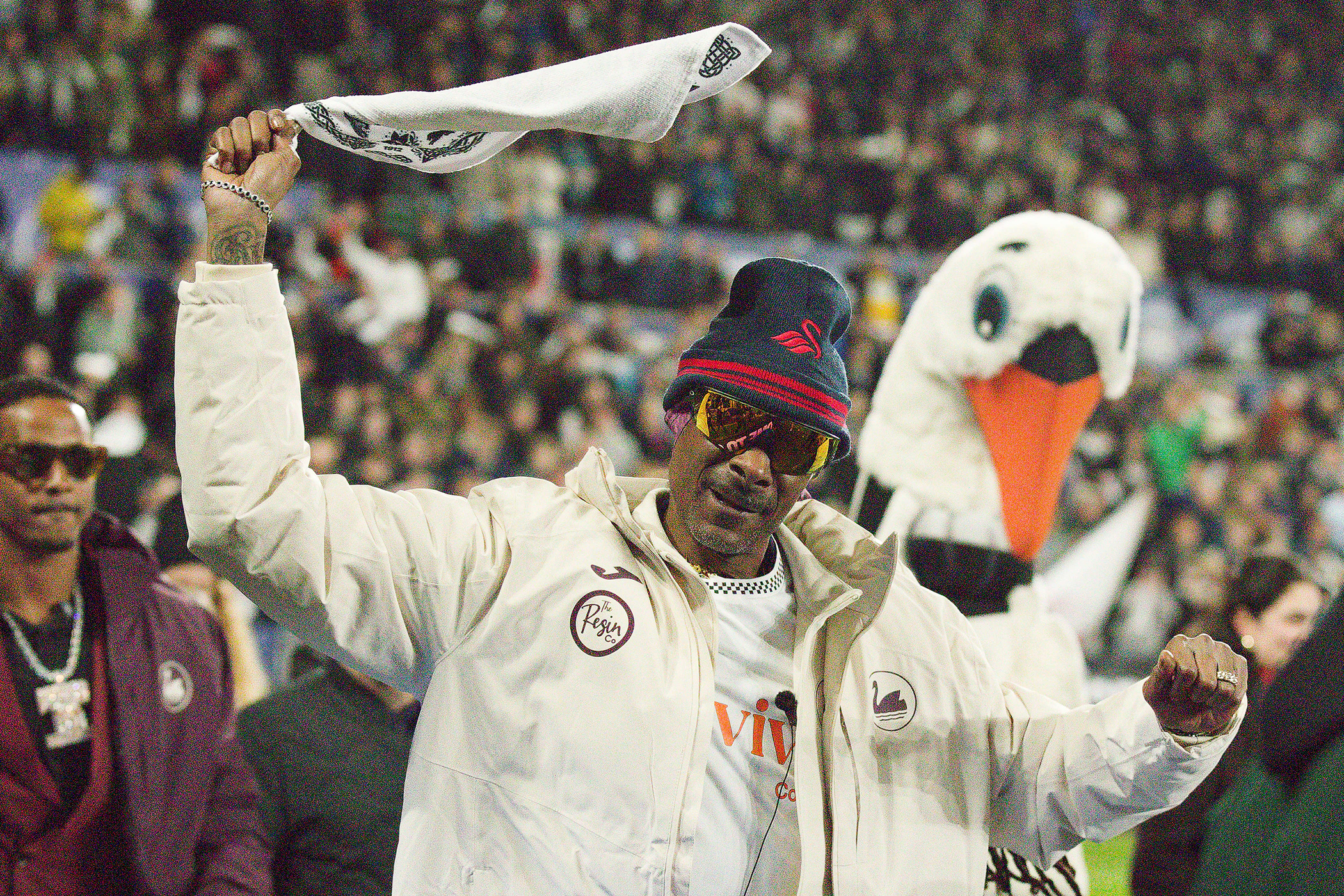

By the time everything is ready, the players are on the pitch and the whistle is about to blow. There is a momentary lull, a collective gathering of breath. And then the banners are unfurled, the flags are raised. The drumbeat starts. The whole section starts to bounce in unison. The noise begins.

The scene would be instantly familiar to anyone who has attended a game in Europe, or who has ever lost an afternoon to YouTube footage of fan displays in Germany, Italy or Argentina. The uniform of black technical gear, Burberry caps and Air Maxes – the staples of Sports Direct chic – and the accents are distinctively local, but everything else is imported. The rhythms, the choreography and the aesthetic have all been borrowed from, or inspired by, the ultras of Europe and South America.

Will Adam used to watch those videos and wonder why football in Britain in general, and Scotland in particular, did not look or sound or feel like that: so active, so vivid, so exciting. “I didn’t really see why we couldn’t have it, too,” he said. And so, along with a few dozen of those standing alongside him in the sunlit Stirlingshire chill, chanting and bouncing, he set out to make it happen.

When a group of Falkirk fans approached Jamie Swinney almost three years ago to ask for a section of the stadium to be reserved for the club’s ultras, the one thing that gave him pause was the name. He knew that ultra was not a synonym for hooligan or for casual. But he also knew that the word ultra carried with it a connotation, an edge.

As chief executive of a fan-owned club, though, he decided to take a calculated risk. He told the aspiring ultras that he would give them a three-game trial. They could use the concourses at the stadium to paint their banners; they would have access to a store cupboard for their materials. They could give it a go. And at the end, he would ask everyone involved, ultras and other fans, for feedback.

“We got a lot of pushback at first,” Swinney said. “There were fans who weren’t happy about a drum being allowed into the stadium. But there were also a lot of people for whom the flags and the drums weren’t an issue. It was the word: they said an ultra group wasn’t the sort of thing the club should be attached to, that it wasn’t on.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

That resistance is not hard to understand. Though Celtic and Rangers both have relatively longstanding factions – and Crystal Palace’s Holmesdale Fanatics have revitalised the atmosphere at Selhurst Park – ultra groups are not a traditional feature of the British football landscape. When they do intrude on our consciousness, it is more often than not in the context of violence, extremism and, occasionally, organised crime.

Over the last few years, though – and particularly after the pandemic – they have taken root across Scotland. Most clubs in the country’s top flight have one or more groups; so do several teams in the lower leagues. But while all of their tribal loyalties are different, many of their origin stories are essentially the same: they were formed in an attempt to bring a little noise, and colour, to games that felt stale and flat.

“The atmosphere in the stadium was dreadful,” as Adam, a founding member of Ultras 1876, the group that approached Swinney for permission to occupy one corner of Falkirk’s home.

“You don’t want to go to football and be passive. It should be a buzz. And to be honest, the football we watch sometimes isn’t really enough.”

The Gorgie Ultras – an umbrella group for various factions at Hearts – offer a similar explanation. “The atmosphere at Tynecastle is traditionally really good,” one of their founders said, speaking anonymously, as is habitual for ultras.

“But I remember going to a European game and it was brutal. The club had wanted to engage the type of clientele who might go to Murrayfield. It was going the same way as England.”

To counteract that, both groups sought inspiration not just in the videos they had seen online, but in physical relationships with ultra groups on the continent. Hearts have a connection with one of the factions at Napoli; Falkirk’s studied the fans of Panionios, a Greek side, in particular detail. This, too, is pretty typical: in that sense, the spread of the idea of ultra groups might be read as a digital phenomenon, further proof of the writer Kyle Chayka’s concept that the internet serves to flatten culture.

Far more significant, though, is the fact that the groups’ motivation is almost entirely analogue. In an essay for the newsletter One Thing this summer, Reid Litman noted that real-life “experiences have come back as the true hunting ground for culture, connection and authority.” Gen Z, in particular, appears to cherish live, immersive events almost as an antidote to how much of existence is now mediated through a screen. There is ample evidence for that in the economic impact for a city in hosting a Taylor Swift concert, or the ticket prices Oasis could command for their reunion tour.

That impulse applies in football, too. The growth of ultra groups in Scotland is part of a pattern that has played out elsewhere in Europe, particularly in countries that are not home to leagues with major television deals.

Attendances in the League of Ireland are booming – more than a million fans attended games last year, a record – a shift that has been, in part, attributed to a post-pandemic desire to “go and experience something.” In Sweden, too, the league responded to declining crowds and dwindling finances by prioritising the feeling of attending a game. There are restrictions on how far fans can be asked to travel for midweek games; the authorities have engaged with ultra groups to try to ensure they can continue to provide a spectacle while minimising the risk of violence.

There is, across the continent, a desire to draw a distinction between football as a television product, consumed passively and remotely, and football as a participatory experience. “As a fan, you want to be active,” said the founding member of the Gorgie Ultras. “You want to get kids in and show them that football is not something that lives in your phone.” The effect has been pronounced. When Swinney asked for feedback to his pilot scheme, many fans had done “a complete 180,” he said. “We had some write in to say they had got it totally wrong.”

Nearly three years on, ticket sales have soared, particularly among younger supporters; many of them want to sit either in the corner reserved for the ultras, or in the sections adjacent to it. The stadium is frequently sold out. The atmosphere, Swinney said, is tangibly improved. “That’s not just to do with the ultras, but it’s part of it,” he said.

Not every club is quite so at ease with the new nature of their support. There are occasional skirmishes between groups, flashpoints, incidents of petty theft. (Falkirk’s store cupboard was broken into a few months ago; they now guard its precise location keenly.) At times, Swinney acknowledged, it is a delicate relationship to manage, even for him. “But we have two and a half years of evidence,” he said. “And this group brings so many positives to the club.”

Within a quarter of an hour of the final whistle, the Falkirk Stadium is virtually empty. A battalion of stewards in high-visibility jackets complete their final sweep. On the pitch, a clutch of unused substitutes sprint up and down, under the watchful eye of their fitness coaches. A few journalists loiter around the dugouts, ready to catch any stray quotes.

The game had ended in bedlam: the centre-back Connor Allan weaving through the Dundee defence to score a last-minute winner, tearing off to celebrate – either by accident or by design – right in front of the ultras, the whole of the section pouring down the stairs to embrace him. Now, though, it is quiet. The only people still here who are not being paid are in the corner of the Kevin McAllister Stand, where a couple of ultras remain.

The clue is in the name: being an ultra, as Will Adam said, requires a commitment that extends beyond the mere 90 minutes of the game itself. In the days before a game, he and his colleagues are “organising displays, painting banners after work,” he said. And after it, too, there are chores to be done: carefully detaching the banners, decoupling the flagpoles, dutifully shuttling all of the equipment back to the store cupboard. “It takes a lot of time,” he said.

Despite that, plenty of fans have been prepared to make that effort. There are many more, those who run the groups say, who would perfectly happily join them. At Hearts, for example, the Gorgie Ultras currently have around 200 “active” members. Another few hundred have a more informal connection to the group. The waiting list for seats in their section at Tynecastle, though, runs to 3,500.

Mostly, those will mirror the demographics of the groups themselves: men, either young or young-at-heart, drawn to the outlaw chic of the scene, horrified by the “sanitised” atmospheres at their club, or – in a few cases – unfortunately but unavoidably attracted to the veiled hint of violence.

But to those involved, those who have already made the commitment, the appeal runs deeper. This month, research by the non-profit Equimundo – which aims to engage boys and men in working towards gender equality – found that British men widely believe that “being a friend” is the most important aspect of manhood, but feel as though they “have to look out for myself, no-one has my back.” The crisis of modern masculinity, in Equimundo’s telling, looks a lot like a crisis of male friendship.

The primary aim of the ultra groups might have been to make going to a football match more fun; their appeal, though, lies in the bonds they forge in an ever-more atomised society, one in which so much of our lives, so many of our relationships, have been digitised. “It is an identity,” as the member of the Gorgie Ultras put it. “It’s not dissimilar to the rise of the casuals in the 1980s. These movements are social, more than anything. They gather strength when people feel a need for belonging.”

That is the root of their appeal; it is what draws fans to the groups, what they see in the banners and the flags, what they feel in the noise: not something to do, but something to be.