When Fleet Street dominated the opinion-forming trade (or believed it did) some sports desks would keep a nuclear-option headline handy in case England started a tournament horribly. “Bring them home,” it would shout.

It was never going to happen. Bobby Robson’s England weren’t going to slink back through Luton airport after a dire opening draw with the Republic of Ireland at Italia 90. Weeks later they returned instead as “heroes” with 100,000 at Luton to greet them. Paul Gascoigne wore fake plastic boobs. Nobody seemed to mind that they’d been knocked out in the semi-finals.

Summoning a national team home is anger fantasy, a shame orgy. In Australia now though, there’s a fresh twist. Instead of the team shipping out, some England fans are apparently sending themselves back home. Or threatening to. They can’t process their anger from the two-day Perth debacle. Most interestingly, they can’t cope with England’s blind adherence to a theory, which they take as an affront.

Never mind that it could all turn round in Brisbane with an England victory in the second Test. There’s a rupture of faith, a disinclination to excuse an England team that too often do what they want in Test cricket, and not what’s required. Many England fans feel they don’t matter to the team – that they flew 9,000 miles to watch recidivism.

Which raises a question central to the potentially epic anticlimax unfolding in this series (I count myself in the camp of those who think it’s too early to give up): who owns a national team? The state, the sport’s governing body, the players, coaching staff or… us?

Starting abysmally isn’t unusual. At the 2007 Rugby World Cup in France, England lost 36-0 to South Africa in the group stage – but still reached the final, where they lost to South Africa again, this time only 15-6.

In the 2005 Ashes, the greatest to be played on these isles, Australia thrashed England by 239 runs in the first Test at Lord’s, where 17 wickets fell on the first day – an echo of Perth last weekend. Another reverberation 20 years ago was England losing their last five second-innings wickets for 22 runs. They weren’t playing Bazball back then. The great 2005 turnaround was on English soil, in English conditions, by a side not chained to their own hypothesis. Yet the outcome – England’s 2-1 series win, sealed at The Oval – still stands as an antidote to premature despair.

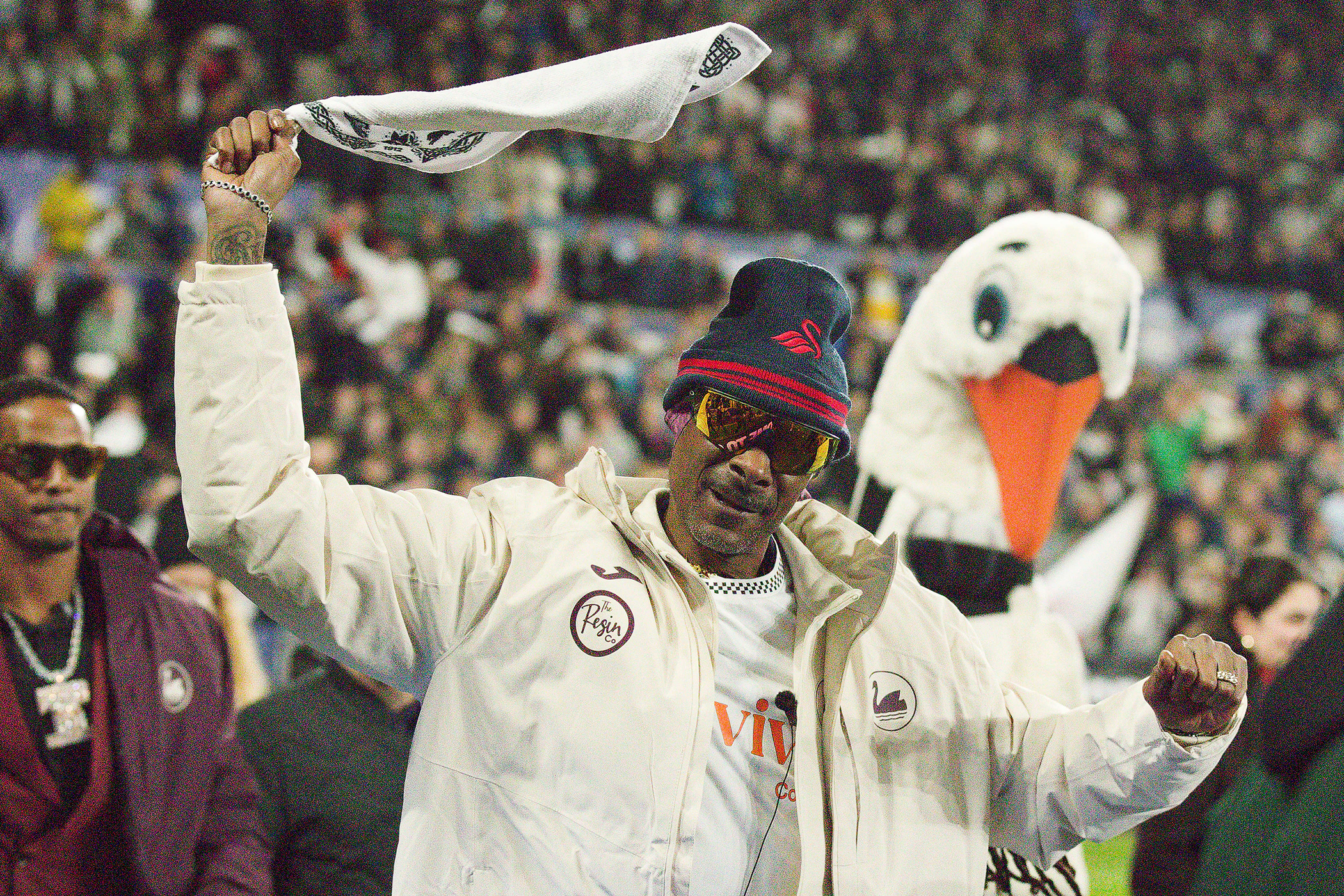

There. That’s the optimistic bit done. But the England management – and the England and Wales Cricket Board, which employs them – should know what a dangerous game they’re playing. The Barmy Army isn’t like the England football crowd. They’re essentially cheerleaders, the sporting arm of the Monster Raving Loony Party. Their default mode is supportive. That could easily change if they start to feel cheated.

“England fans love this team, but if I was in the XI I’d be fearful the supporters will turn because the side keeps making the same mistakes,” the 2005 captain Michael Vaughan wrote this week. The risk of a fan revolt is coming through loud and clear from Australia, where it’s hard enough to deal with the home crowd calling you “Pommie bastards” without your own lot joining in.

England’s followers are experiencing Bazball as a kind of disenfranchisement. Granted, there’s a double standard. Many go home glowing when England put 500 on the board with insouciant drives, hooks and ramps. When it works they like its hallucinogenic qualities. They also know their cricket well enough to see when it’s self-destructive vanity, as it was in Perth. All most of them crave is calculation – and balance.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

So who does own England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland? Who gets a say in what they do, how they play? There is no Act of Parliament enshrining an England, Scotland or Wales team as public property.

In England, they began as arbitrary collections of “All-England” players, chosen by self-appointed match makers. In cricket, the “All-England” label was first applied in 1793. In football, England and Scotland invented the international game in 1872, while private schools mostly shaped the laws and offered up 11 chaps to play the matches.

When governing bodies sprang up, they took on the role of “governing” national teams and assumed moral ownership. But the public have never seen it that way. They’ve always claimed their own personal share in the nation’s football, cricket or rugby sides, by virtue of birth certificate or citizenship. Here was one of the few industries that could never be privatised because it belonged to everyone.

International coaches and players sometimes forget that they work for us, not the other way round, tiresome though that can be, when your own fans are spewing abuse. With England’s cricket set-up in Perth, there was a sense of the leadership regarding the England team as a private project, a vehicle for a dream, with the fans there as consumers, with a duty to cheer and clap.

If it’s hard to say who owns the England cricket team, it’s easy to say who doesn’t. Not Brendon McCullum, or his fellow daredevils, who need to know in Brisbane that it’s not all about them.

Photograph by Robbie Stephenson/PA