So you’re meant to care when a bunch of sportswriters at the The Washington Post are told their days of being paid to cover the Super Bowl or Winter Olympics are over? You’re expected to weep for them when the Post’s frost-bitten Kyiv correspondent was also “pink-slipped” in the cull?

There ends a rhetorical device used in old American sports columns that grabbed you by the lapel. The best were punchy, rich in the American vernacular and often unforgettable. The most celebrated sportswriting was a beacon of lyrical prose fuelled by the pulsating energy of the ballpark. Every year there was a hardback “best of” compilation.

Last week’s axing of almost the entire Washington Post sports department left only a few still standing to cover sport as “a cultural and societal phenomenon”, which it always was.

News outlet deaths aren’t new. Local papers have fallen all across America. As far back as 1963, the peerless Jimmy Breslin described the demise of the New York Mirror. Breslin wrote: “Over in a corner of the editorial room, in the part used by the sports department, George Girsch, a copydesk man, picked up the telephone. Toney Betts, the Mirror’s racing writer, was calling from the Aqueduct Race Track.

‘What’s this?’ Betts asked.

‘It’s right, the paper is gone,’ Girsch said.”

All Betts could think of was to find two final winning tips for the last edition.

Breslin was the archetype of a writer who could glide from the Vietnam war to Watergate to New York life and sport with a single authorial voice.

In a piece tracking Joe Namath, New York Jets quarterback and playboy, through the nightspots of their troubled city, in 1969, Breslin wrote: “When you live in fires and funerals and strikes and rats and crowds and people screaming in the night, sports is the only thing that makes any sense.”

The work of Breslin and his finest contemporaries was blessed with a song-like quality. Constant access to the stars lent intimacy to their reporting. Reporters and performers shared stadiums, training grounds and even locker rooms. City newspapers were the conduit between team and fans. Writers had the astonishing privilege of observing close up every nuance of America’s favourite games.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The past tense might be inappropriate. Sportswriting in America remains a respected craft with many gifted operators. The frustrated poets who rode high on expenses and faced no competition from digital are reincarnated across Substack and a sprinkling of intelligent start-up sites.

Three years ago the New York Times closed its sports desk and effectively franchised out its coverage to The Athletic, which it had bought for $550m. The Athletic is high class but the deal could not disguise the New York Times’ “shuttering” one of its most prestigious sections.

Sport is a truth-preserving activity because it is governed by laws people actually care about

Sport is a truth-preserving activity because it is governed by laws people actually care about

Breslin’s heirs can still write but what we call “heritage” media has abandoned them, surrendering to the mania for video clips, aggregation and news-snacking. “Your audience is halved,” the British executive Will Lewis once told Washington Post journalists. “People are not reading your stuff. I can’t sugarcoat it any more.”

Lewis, the executioner last week, joined the executed, losing his own job, after parading his insensitivity on the Super Bowl’s red carpet.

Much the same subservience to “market change” has happened in Britain, with huge culls and influencers replacing trained reporters. But to return to the question at the top, who does it matter to, except the victims and their families? Why should any non-journalist care? Because the deracination of independent sports reporting in America is a microcosm of the retreat from factual journalism in the more important fields of politics and society.

If sport is churn, and “content”, and not scrutiny, or human observation, or informed analysis, then every other form of cultural reportage might as well be “shuttered” too.

Sport happens to be a truth-preserving activity because it’s governed by laws people actually care about. Think of how football fans in this country detest diving or what doping has done to the Olympic 100m. People turned away in disgust. Properly governed sport holds the line for the principle of the rule of law.

In America, the old-timers, John Schulian, editor of The Great American Sports Page recalls, wore “suits and ties, fedoras and tweed overcoats. Not just the big hitters like Damon Runyon and Red Smith, but everybody.”

Some were egomaniacs and insufferable and almost all were male. It was small consolation that the country’s first female big city-columnist, Diane K Shah, took a call from Cary Grant telling her he loved her writing.

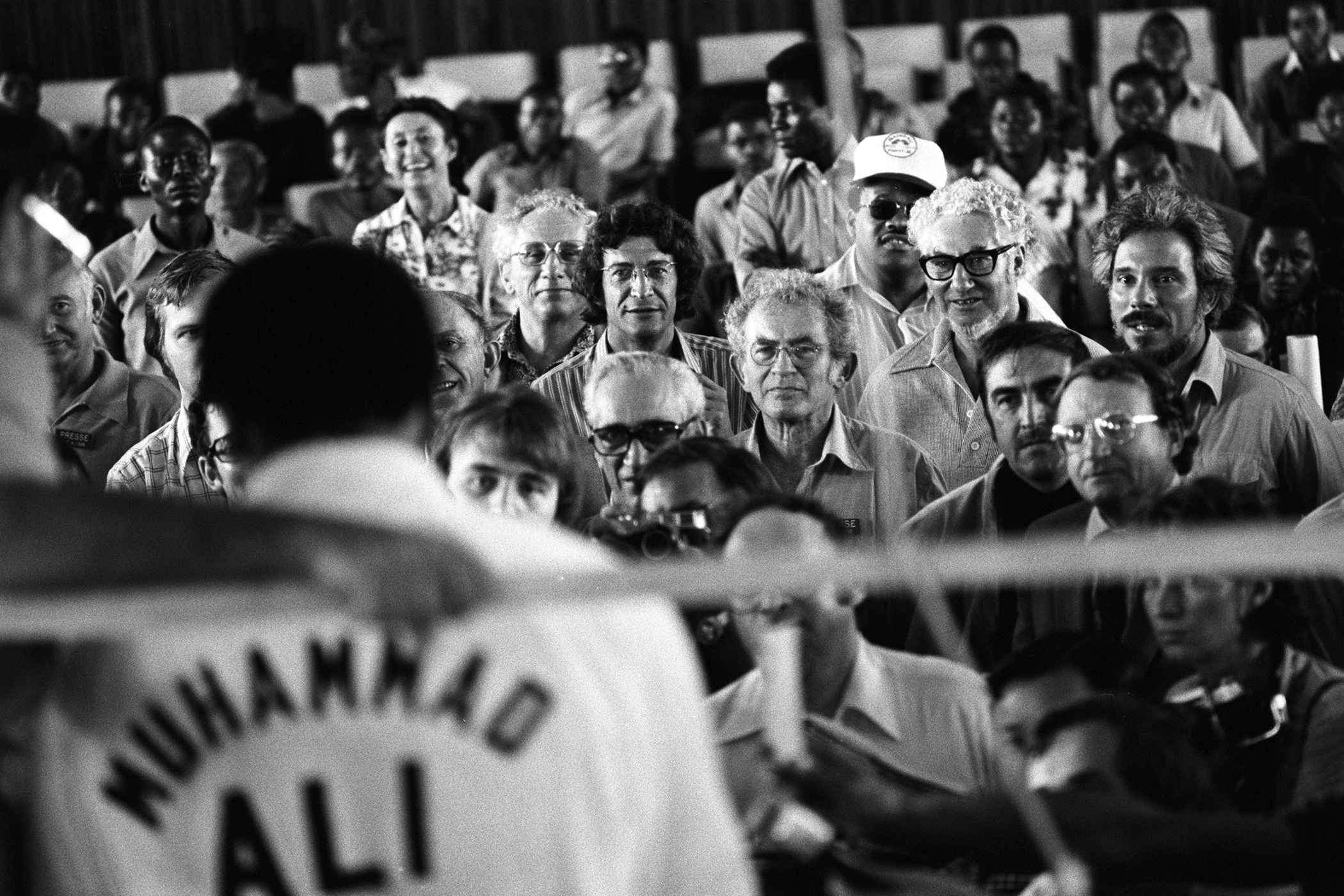

A personal memory is of taking a ringside seat at a fight in Las Vegas and turning to see an elderly colleague who radiated studious detachment squeezed in next to me: Budd Schulberg, author of On the Waterfront and What Makes Sammy Run. In America no distinction was made between sportswriting and “serious” literature. Schulberg, Norman Mailer, Joyce Carol Oates, David Remnick and countless others beat a path to the game.

The lucky ones would jump in a car with their subject, go to their home, to the bar and restaurant, and into the recesses of the stadium for long confessionals. They applied the Nora Ephron principle: “Everything is copy.”

In the flight from independent journalism at The Washington Post, where the Watergate scandal was exposed, sport must have felt like an easy one to get rid of. Sacking Lizzie Johnson “in the middle of a war zone” (her words) in Ukraine seemed more momentous. The common denominator is the white flag of an American institution’s surrender.

Feature image: Iconic cultural writers, Budd Schulberg and Norman Mailer attend Muhammad Ali's press call previewing his 1974 WBC/WBA World Heavyweight title fight against George Foreman.

Photograph by Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated via Getty Images