Welcome to the Sensemaker, our daily newsletter. It features calm and clear analysis on the stories driving the news across tech, politics, finance, culture and more. The Sensemaker will appear here every morning, but to receive it in your email inbox, sign up on our newsletters page.

Defence, passports and free movement for young people were among the most talked-about topics at this week’s EU-UK summit. Less widely discussed: energy trading.

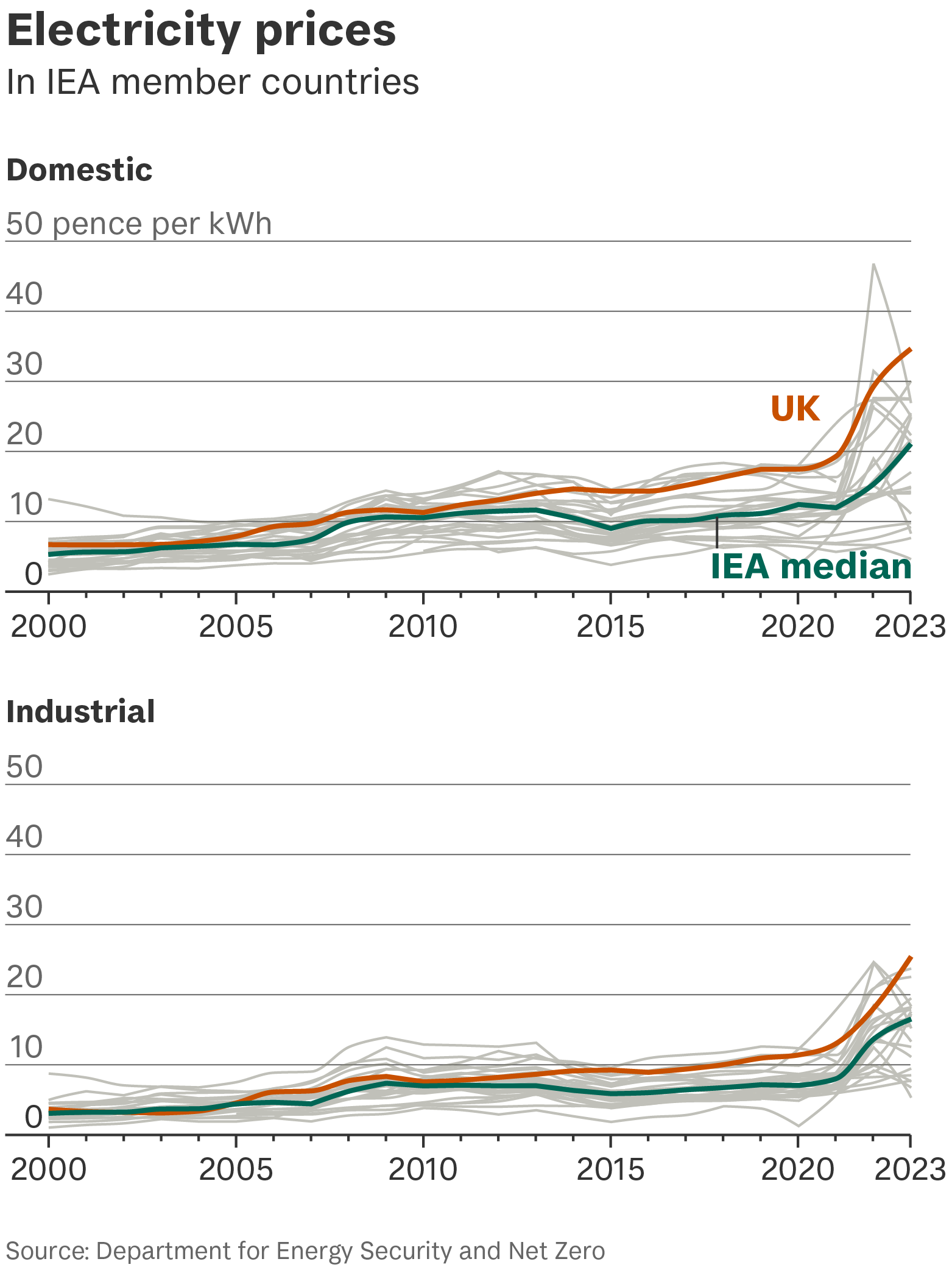

So what? It matters. The UK’s electricity prices are the highest in the developed world. This doesn’t just pinch the pockets of consumers. It also makes British steel and other goods far more expensive than those produced in other countries. The deal signed on Monday could change that by starting to reintegrate the EU and UK electricity and carbon markets.

In 2023, British factories paid 25.85p per kilowatt hour for power. That’s

•

four times higher than in the US;

•

2.6 times higher than South Korea; and

•

nearly triple the price in Canada, Norway, Finland, Sweden, New Zealand and Portugal, which all charge less than 10p.

Put off. This discourages investors and weighs on British industry. The cost of running a steel mill in the UK, for example, is £50 million more a year than in France, according to British Steel.

“If you are building a new, big industrial plant, you want to go where energy is cheap, and right now that’s not the UK,” says Adam Bell, the former head of Energy Strategy at the Department for Business and Trade.

Going green. On the face of it, energy prices should be coming down. In 2024, most of the UK’s power came from renewables for the first time. Green energy means fewer emissions but it’s also much cheaper than fossil fuels. The unit production costs of solar and wind power are currently on average about 75% lower than electricity from gas.

“If we actually paid the price of what our electricity now costs to produce, our bills would be substantially cheaper,” says Michael Grubb, professor of energy and climate change at University College London.

Rain or shine. But renewable power plants aren’t always on. Because of their intermittent supply, gas plants still make up the difference during times of low supply.

Gas guzzlers. Under the UK’s “marginal pricing” model, energy suppliers set prices based on the most expensive energy source. In the UK, fossil fuels set the price of electricity 98% of the time, compared with

•

24% of the time in Germany;

•

7% in France;

•

1% in Norway; and

•

the European average of about 40%.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Spike. This makes British consumers especially vulnerable to changes in global gas prices, which have soared since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, costing the UK an extra £90 billion over the last four years, or an extra £1,3000 per person according to the Energy & Climate Intelligence Unit.

Added costs. The UK also has an ageing national grid. The cost of operating, maintaining and upgrading it is added to consumers’ bills as a “network cost.”

Steady on. Other countries have constant sources of energy that are not gas. France has its nuclear power stations. Norway has a huge series of hydro dams. The UK lacks an equivalent.

Neighbourly help. Labour hopes loosening restrictions on energy trading with the EU following this week’s agreement could help. This would allow the UK to import more from the continent when demand is high but supply is low, instead of firing up gas plants.

Not enough. Other interventions are needed, though. Currently, the government pays wind farms in some parts of the country to cut output when they supply more electricity than the grid can handle, even as it pays gas plants to turn on to meet dips in supply in other parts of the grid. This inefficient balancing act cost more than £2 billion last year.

In the end…a massive ramp-up of renewable power is what’s needed most, but new plants face hurdles. The former boss of Tesco is struggling to get the green light for a £25 billion project linking Moroccan solar farms to Devon, while a Danish developer has halted plans for a huge new wind farm in the North Sea. Supply chain bottlenecks were driving up installation costs.

Photograph by Chris Ratcliffe/Bloomberg via Getty Images