Martin Parr was one of a kind. No photographer in the last 50 years has made such an impression on the field. He changed photography by the way his pictures looked, but also by his total commitment to the medium itself, and those who practise it, young and old.

I first met Martin when the Bodleian library – where I am a librarian – was seeking support for the acquisition of the personal archive of William Henry Fox Talbot, one of the inventors of photography. I asked some photographers to donate prints to be sold in a special benefit auction at Sotheby’s. Martin was the first person I approached, and the first to say yes: he was outraged that photography was not as well regarded in Britain as it should be, and he was keen to support initiatives that helped change the dialogue. He invited me to Bristol, and showed me his collection of photobooks. I was blown away. Over lunch we hatched a plan for him to come and photograph a year in the life of Oxford University and to make a photobook (which was published in 2017). He was the first photographer to get deeply inside the university. He loved the colourful ceremonies, but was even more delighted to discover the college tortoise keepers, who he featured magnificently in the book. He was the first to document a tutorial (in Balliol). Martin always made a point of puncturing pomposity: in All Souls he made two juxtaposed portraits: an eminent professor is given the same pose as one of the college cleaners. The book includes a portrait of Simon Armitage, then professor of poetry at Oxford, next to a hanging rail and other everyday objects. Armitage told me at the time: “Parr is a genius. I distinctly remember him moving me towards the plastic bag and the brolly.” The Oxford work was one element of his multi-decade project to document the British establishment, which came together in 2019 as an exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery (Only Human).

Martin introduced me to a number of photographers who needed a home for their archives. One of them, Paddy Summerfield, duly gifted his to the library. We exhibited a retrospective of his work as part of the PhotoOxford festival in the autumn, and Martin came to open the show. We had dinner afterwards and he was full of ideas and enthusiasm, buzzing about the show of his photobooks in Nuremberg, where he had just been. My wife and I talked afterwards about his extraordinary reserves of energy. The next day Susie told me that, somewhat typically, Martin hadn’t mentioned to us that his cancer had returned, with a grim diagnosis. We all thought he had more time.

One of the things that drew us together was a love of photobooks. For Martin, the book was the pre-eminent medium for disseminating photography, and he made almost 150 of them, from Bad Weather (1982) to Fashion Faux Parr (2024) – he couldn’t resist a pun. Many of his books have been groundbreaking, hugely influential on other photographers, designers and creatives. He worked with many different publishers and loved all the details about design, paper, sequencing and layout. One of the most successful, Common Sense (1999), was made with the publisher Dewi Lewis. This book of full-bleed intense colour images has no text or white space at all. I asked them why they chose for the first image a shot of a girl blowing a huge bubblegum bubble: they needed some space for Martin to sign his name at the many book signings that would come.

Martin’s obsession with photobooks had expression in other ways: he formed a massive collection (now at the Tate), charted them with Gerry Badger in the three volume The Photobook: A History (2004-14) and created an annual photobook festival in Bristol.

For Nicholas Serota, the former director of the Tate and chairman of Arts Council England: “Martin transformed our view about the role of photography in society. His own fresh view of the customs and rituals of British life, and his attention to communities that had been overlooked or disregarded, captured the imagination of many, as we saw in their response to numerous exhibitions.”

Grayson Perry told me that: “One mark of a great artist is that they change the way we look. I expect every day somewhere in the world someone sees a lurid plate of food or a weird local ritual and exclaims: ‘That looks like a Martin Parr photograph!’”

What is less well known was Martin’s qualities of friendship. He was very straightforwardly kind, loyal and generous. Brian Griffin, who studied at Manchester Polytechnic with Martin and Daniel Meadows, told me that it was Martin who quietly but decisively resurrected his career during his recovery from addiction.

Since his death, tributes to Martin have been staggering – photographers, institutions, publishers and ordinary people have all shared their love of his work, admiration of his humour, or their friendship with him. Martin Parr was one of Britain’s greatest visual ambassadors, and Britain must honour Martin Parr in return.

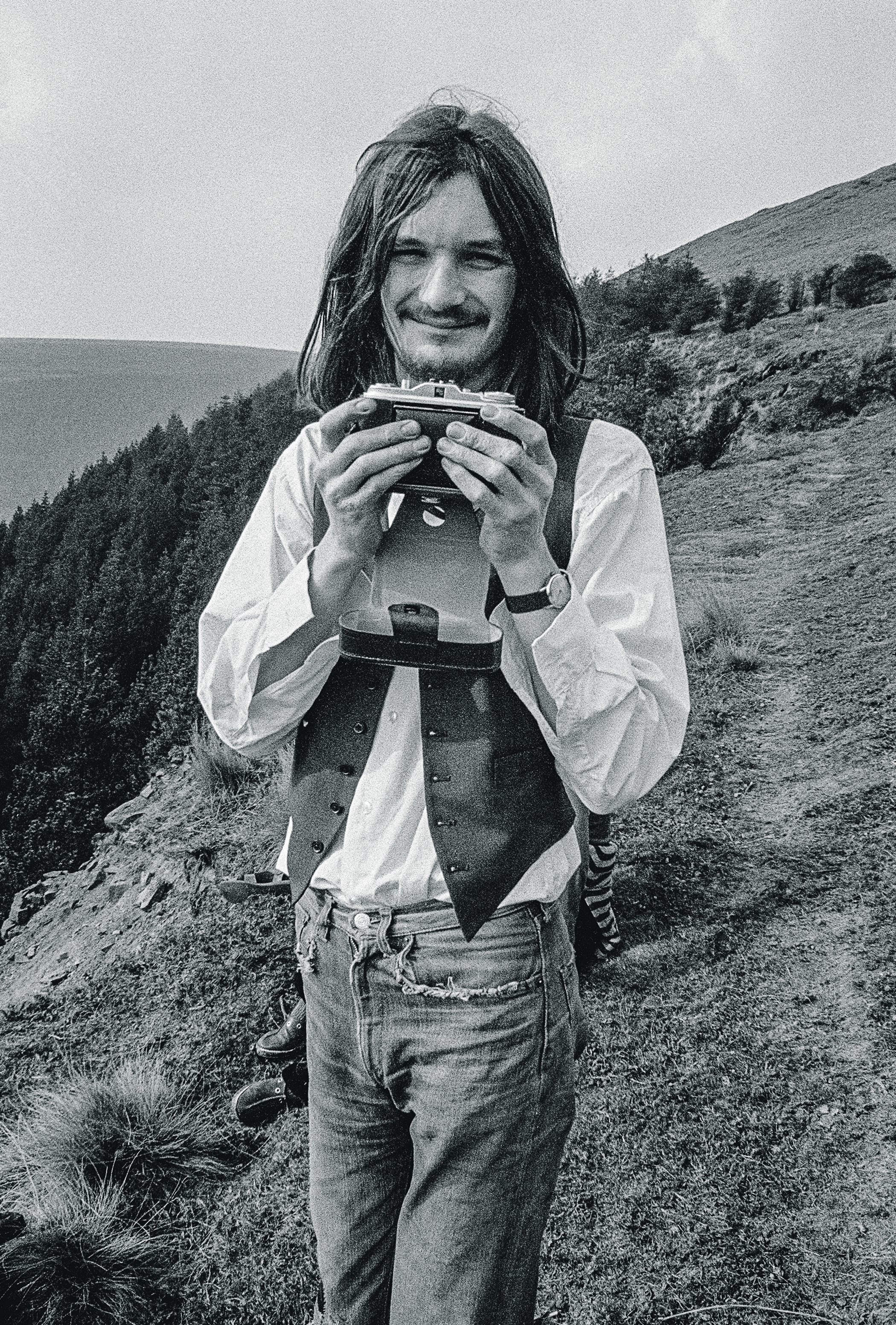

Photograph by Daniel Meadows/CBS

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy