When David Baltimore received the Nobel prize for physiology or medicine in 1975, he said that a virologist was among the luckiest of scientists. “He can see into his chosen pet down to the details of all its molecules.” Ever since high school, he had been fascinated by the tiniest building blocks of life, where giant discoveries can be made.

In 1970, while studying leukaemia in mice, Baltimore discovered an enzyme that challenged the common understanding of how genetic information is transmitted. Previously, it was thought that proteins were produced in living cells by molecules known as RNA that contained a copy of DNA. However, some viruses, later known as retroviruses, worked in the opposite direction, corrupting the DNA in a host cell. Baltimore found that this reverse effect was created by an enzyme called a transcriptase. His discovery allowed scientists to insert healthy genes into DNA, leading to breakthroughs in the treatment of cancer and HIV. In 1975, it earned him the Nobel prize with Renato Dulbecco and Howard Martin.

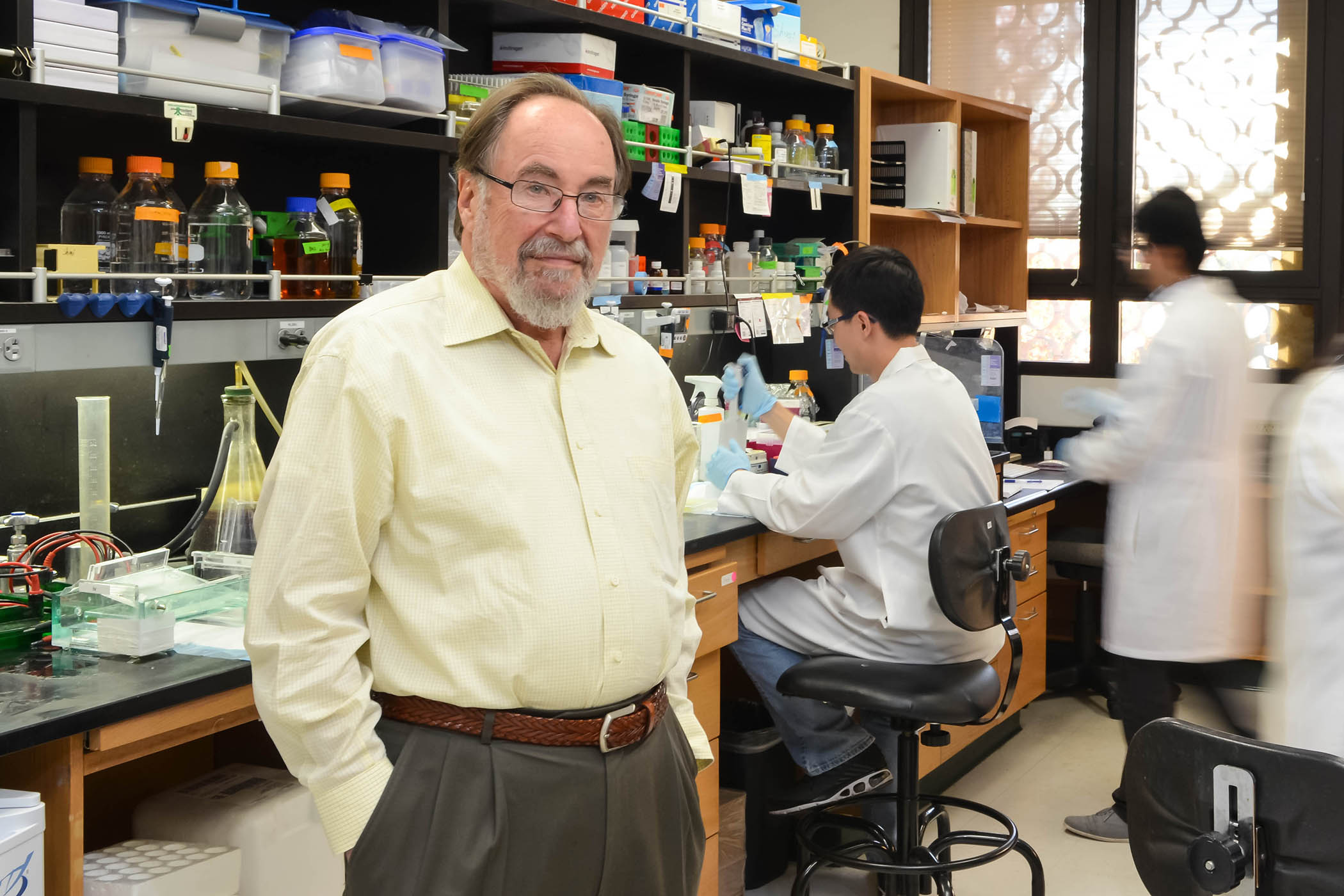

“In a single stroke, David demonstrated something that had been considered to be impossible for more than 20 years,” said Carlos Lois, a colleague at Caltech (the California Institute of Technology), where Baltimore was later president. Thomas Rosenbaum, the current president, said his work had “transformed biology and medicine”, while Thomas Palfrey, an economics fellow there, said: “He was one of these people who put his foot on the accelerator and never let up his whole life.”

Baltimore was born in Manhattan in 1938, the son of an orthodox Jewish father who sold women’s clothes. His interest in molecular biology was ignited as a teenager when his mother sent him to a summer school at a lab oratory in Maine that studied mouse genetics. “I came back and said: ‘This is what my life is going to be,’” he said.

He was one of these people who put his foot on the accelerator and never let up his whole life

He was one of these people who put his foot on the accelerator and never let up his whole life

Thomas Palfrey, Caltech

Baltimore took his first degree at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania, then moved to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) before completing his PhD in animal virology at New York’s Rockefeller University. Dulbecco brought him to the Salk Institute in San Diego in 1965, where he met his future wife, Alice Huang, a fellow virologist, before returning to MIT.

In 1982, funded by a large donation by a philanthropist, he founded MIT’s Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, which within a decade was named as the world’s best institution for research into molecular biology and genetics.

Appointed president of the Rockefeller in 1990, he had to resign after 18 months because of an allegation of fraud against a fellow biologist at MIT that led to a congressional investigation.

Although Thereza Imanishi-Kari was not working in Baltimore’s laboratory when she was accused of fabricating data, he had co-authored a paper with her and so robustly defended his colleague that the papers referred to the allegations as “the Baltimore affair”. After giving the congressman who led the investigation a half-hour dressing down that was described as “high drama”, he resigned as Rockefeller president. Five years later, an appeals panel found the accusations of fraud to be unfounded.

Despite saying that he would “not miss administration at all” and that he was very happy to return to research, Baltimore became president of Caltech in 1997, where he promoted research into gene therapy to treat Aids and cancer. He caused another, more aesthetic, controversy when he tried to install a large steel piece of postmodern art by the sculptor Richard Serra on one of Caltech’s largest lawns. Baltimore arrived at work to find a trashed car, broken filing cabinets and other assorted junk dumped on the lawn with a sign sarcastically declaring it to be worth $1.8m, the sum he intended to spend on Serra’s work. Baltimore backed down.

He despaired of being a scientist in the age of Donald Trump

He despaired of being a scientist in the age of Donald Trump

Baltimore was often frustrated by the media’s eagerness to stoke public fear during a crisis. In 2003, during the Sars outbreak, when Americans were being urged to stay away from Chinese restaurants in case they caught the respiratory virus, he called for the actual risk to be put into perspective, though admitted that this was in part because he was married to a Chinese woman.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

He also despaired of being a scientist in the age of Donald Trump, telling an Australian broadcaster in 2019: “In the past… the bulk of the population felt that we [scientists] were doing work that was positive for civilisation. We’re not sure that people see us that way any more – and certainly the president and people he has circled round himself don’t. They want to create facts that satisfy their political needs.” However, he pleased conspiracy theorists two years later when he expressed his belief that Covid-19 had been created in a laboratory rather than evolving in nature.

As a prominent scientist, Baltimore was, inevitably, often asked to explain the impossible. He said that people regularly emailed him to ask for the meaning of life. He would explain to them that life’s meaning for most of us can be found in friends, dogs, religion and writing – but that at Caltech it was in “the continual contest with nature”.

The most enjoyable part of his job, he said, was when a student achieved an unexpected result. “It’s the same thrill all over again,” he said in 2006. “You go home and think about it when you sleep and you know there is something new in the world.”

David Baltimore, molecular biologist, was born on 7 March 1938 and died on 6 September 2025, aged 87

Photograph courtesy Caltech