If a palaeontologist says mankind faces “imminent extinction”, it is not a reason to stop buying green bananas. In geological terms, “soon” may still mean we have a few million years to go. However, Michael Boulter was not joking when he warned a conference of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 2000 that the human race was speeding up its own elimination.

Professor Boulter’s team at the University of East London had studied the vast fossil record, modelling how species emerge, peak and decline, and found that large mammals are becoming extinct at a much faster rate than predicted. “The Earth needs, from time to time, culls,” he said. “From the evidence we have, there is reason to believe that we humans are interfering with the environment so much that we are making ourselves extinct.” He said the “good news” was that life on Earth would continue happily without humans, adding: “Of course, it’s poor news for us.”

Boulter expanded on this in his 2002 book Extinction: Evolution and the End of Man, in which he warned that a small trigger event could cause the collapse of the whole network, much as adding a fatal last grain of sand to an overheaped pile can create a series of landslides. Mike Benton, professor of vertebrate palaeontology at the University of Bristol, called him a “pioneer” whose book showed how major crises of the past relate to the Earth’s current problems.

Michael Charles Boulter was born in Leicester in 1942. His father, who was badly wounded at the Somme, worked in a Spitfire factory and later made fishing bags from the canvas lining of old tyres. They lived in poverty, and Boulter recalled that the family possessed only four books: Treasure Island, an encyclopaedia, one on gardening and The Observer’s Book of Pond Life.

Their only child was expected to get a job in the city’s hosiery factory. However, Boulter’s interest in history and geology had been stimulated by family picnics in the Precambrian landscape of Bradgate Park, where some of the planet’s oldest fossils were discovered when he was a boy, and by being taught at school by the same master, Bert Howard, who had helped the scientist CP Snow to get a place at university 30 years earlier.

In 1968, Boulter fled Czechoslovakia, carefully protecting a 30-million-year-old seed. Unfortunately it was destroyed at Heathrow when a customs officer opened its container and sneezed

In 1968, Boulter fled Czechoslovakia, carefully protecting a 30-million-year-old seed. Unfortunately it was destroyed at Heathrow when a customs officer opened its container and sneezed

He went, as his parents put it, to “do science in London”, which he felt would be his escape route. He studied botany, geology and chemistry at University College before writing a PhD on flora in Derbyshire after the extinction of the dinosaurs. In 1961, a student from Liverpool introduced him in a Bloomsbury pub to a band who were passing through on their way to Hamburg. They went back to Boulter’s digs and drank deep into the night. “At some point one of them had to be sick in my sink and in doing so spat out a tooth,” he recalled. Fifty years later, after one of John Lennon’s teeth sold at auction for £19,000, he regretted not keeping it as a souvenir.

After graduating, Boulter said he had walked into a phone box with five pennies to make calls and come out with three part-time lecturing jobs. The main one was at West Ham Technical College and then at Imperial College, where he researched botany of the Tertiary period. In 1968, he was working in Czechoslovakia during the Soviet suppression of the uprising and had to flee the country, carefully protecting a 30-million-year-old fossilised seed. Unfortunately it was destroyed at Heathrow when a customs officer opened its container and sneezed.

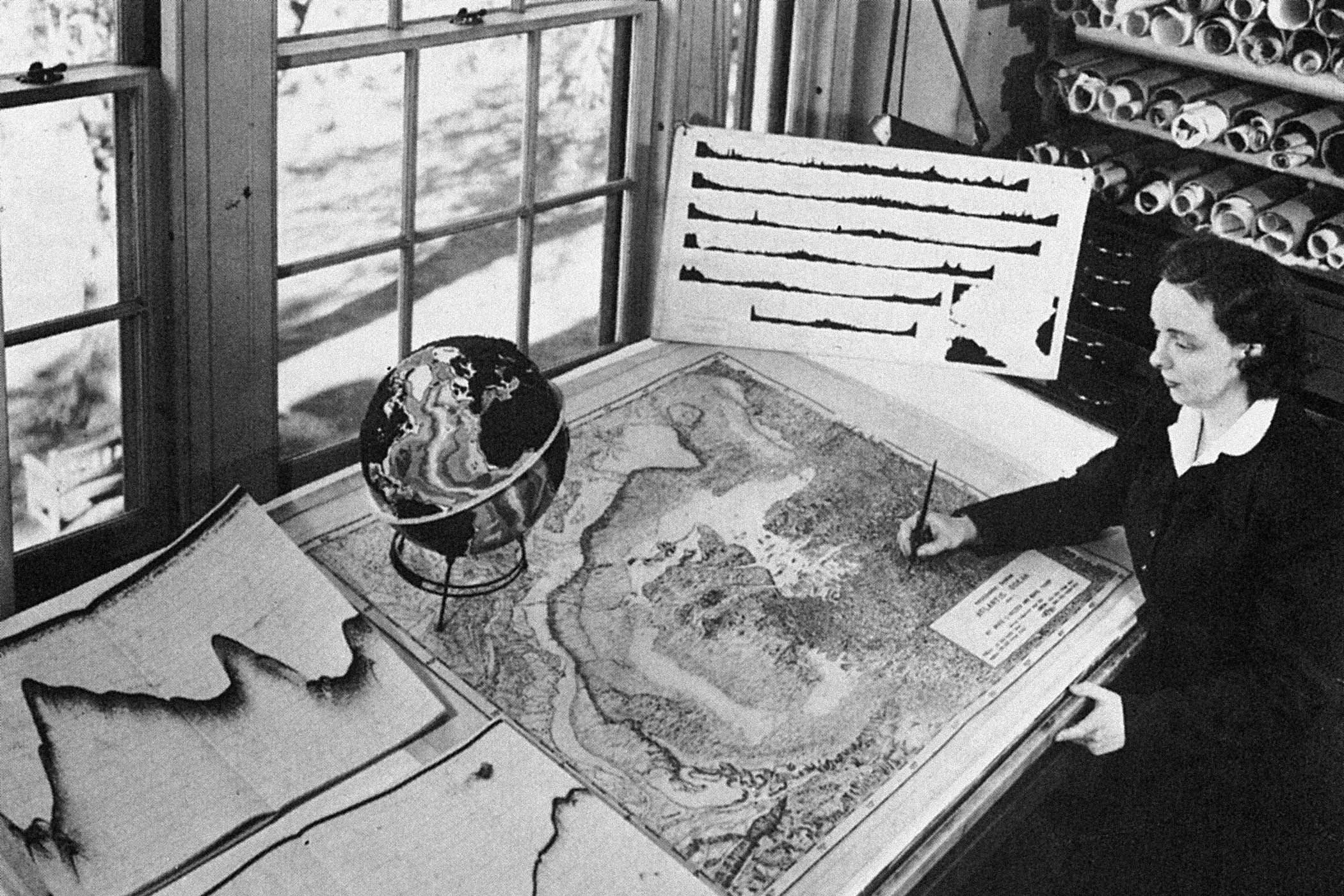

He married Biddy Arnott, a Jungian analyst, in 1975 and they had two sons, Tom and Alex. From 1989 to 2002, he was professor of palaeobiology at UEL. In 1997, he wrote a paper on new evidence of a rich biosystem found on a submerged microcontinent in the north Atlantic, which had existed tens of millions of years ago when the ocean was a mere river with ambitions. With characteristic wry humour, he liked to joke that he had discovered Atlantis. He later worked at the Natural History Museum.

In retirement, Boulter turned his attention to scientific biography, a writing form for which he had talent. He co-wrote an engaging book on the scientist members of the Savile Club in Mayfair, of which he was a trustee, to mark its 150th anniversary in 2018. The previous year he had published Bloomsbury Scientists, looking at the network who lived and worked on either side of the Great War in close proximity to the arguably more celebrated writers and artists but who showed no less creative energy.

In 2008, he wrote Darwin’s Garden, about the scientist’s life at his 16-acre home in Kent, where, far from the decks of the Beagle, he polished and then published his theories on evolution while observing nature’s variety during his daily stroll along a “thinking path” that he called the Sandwalk. “His garden was his laboratory,” Boulter wrote.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Boulter found his own Eden for research in the valleys of the Greek island of Andros, where he built a holiday home after being given six months to live after a diagnosis of oesophageal cancer. He survived for 30 years, proving that even when experts warn the end is nigh, life may still have plenty more to unfold.

Michael Boulter, palaeontologist, was born on 22 November 1942 and died on 4 December 2025, aged 83

Photograph by Photograph by Guillem Lopez/Starstock/Photoshot