I forcefully remember being on the upper deck of a bus with my mother when I was about 10. This was in the outer London suburbs, and I was burbling away like a 10-year-old – about what, I have no memory – when my mother stopped me with the words: “You’ve got too much imagination.” Fortunately, I didn’t resent this rebuke, as I had no idea what the word meant, let alone that in decades to come I would make my living from this abstract noun.

The implications of my mother’s unheeded words would have been clear to her at least. Don’t go around with your head in the clouds, keep your feet on the ground, work hard, love sensibly, get a job, wife, children, and teach them in turn not to give way to reverie. Imagination is dangerous. My mother was an educated woman, and would have known Shakespeare’s lines, “The lunatic, the lover, and the poet / Are of imagination all compact.” This faculty, once indulged, might plunge you into the mental asylum, the catastrophe of operatic passion, or the indigence of versification. And the barriers between them all are thin. The Swiss writer Robert Walser spent many years in an asylum; one day he was visited by a friend who asked him if he was writing. “You don’t understand,” retorted Walser, “I’m not here to write, but to be mad.” (Which sounds pretty sane to me.)

If we deconstruct the word in an unetymological fashion, we can find it contains the following items: I, imag(e), magi and nation. So: the individual lives in a country where sorcerers and wise men offer the population visions which they may learn from and live by. And that sounds interesting, but still dangerous, doesn’t it, especially if you are on the top deck of a bus with your small son. Plato banished poets from his ideal state, because they strayed away from reality. And Plato was a wise man, as everybody knows.

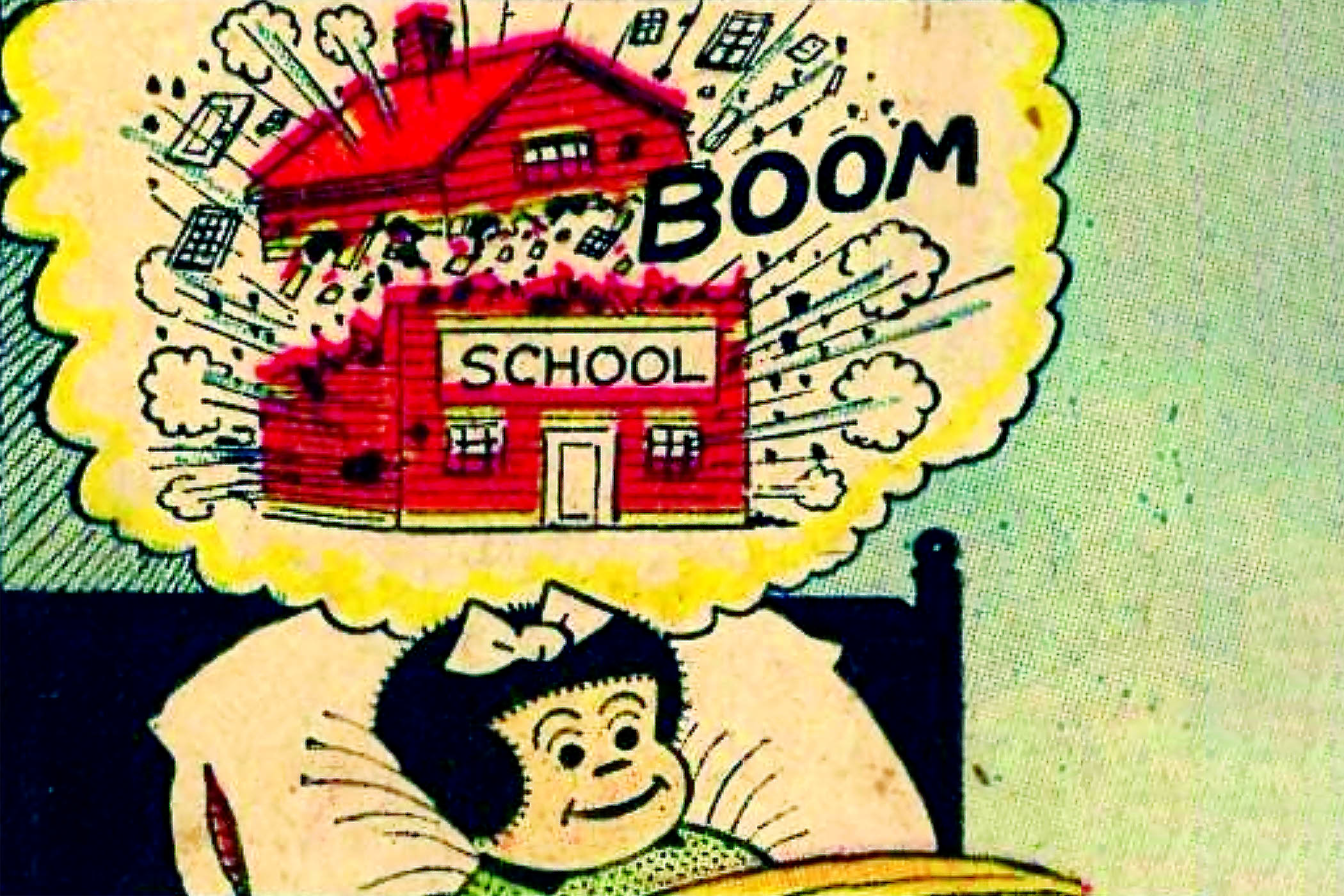

And in a way he was right, because the imagination is dangerous when seen from the other side. It is an alternative power. It can warn us, and it can make us dream. It can picture a better, cleaner, fairer world than the authorities are able or willing to seek. It can conjure up both utopias and dystopias. It can decline the tyranny of religion, even though it helped develop its defining myths in the first place. Books and artworks are still being destroyed, and where they are burnt, artists and writers will be burnt shortly afterwards – or, to save kindling, merely shot. So let us hail the imagination, and celebrate its expansive and subversive powers. A world without imagination would be like living on a dusty planet with nothing but methane to breathe.

The Redstone Diary 2026: Imagining, edited by Julian Rothenstein with an introduction and texts selected by Julian Barnes, is published by Redstone Press at £19.95. Order a copy at The Observer Shop for £19.95. Delivery charges may apply.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy