Like most people, I own my share of what we might call “acceptable fakes”: paste earrings, a Chanel-adjacent jacket, an orange-inflected silk scarf that could almost be Hermès. And I feel fine about them all: originality is nothing but judicious imitation, as Voltaire famously said. Occasionally, though, I do like to go the whole hog. On a shelf by my desk is what looks like a fossil: a rudimentary fish imprinted on pale stone for all eternity. Except that it isn’t – a fossil, I mean. Pick it up. In the hand, it is as light as aerated concrete. Look closely and you can see the marks left by tools that undoubtedly necessitated a plug and electricity.

What’s strange about the history of this particular fake is not that I knew it was a good-looking counterfeit when I bought it 20 years ago in Byblos, Lebanon (which I absolutely did), but that I haggled so fiercely for it. When the owner of the little tourist shop boasted shamelessly to me of its authenticity, I should have walked away – and yet, I didn’t. Somehow, his grandiose fibs only added to its attraction. As a child, I was obsessed by Piltdown Man, a notorious fraud of 1912 in which an amateur archaeologist named Charles Dawson produced a collection of bones and announced them to be the “missing link” between apes and man – and perhaps some of that fascination has stayed with me. In the end, my phoney coelanthe gives me almost as much pleasure as the real ammonite I’ve long kept beside it.

Not everyone is the victim of a dupe. Sometimes, they’re willing accomplices

Not everyone is the victim of a dupe. Sometimes, they’re willing accomplices

It seems to me that fakes sit on a spectrum. The criminal trade in counterfeit luxuries is vast, and often funds illegal activities, including human trafficking. The man or woman who’s willing to spend thousands at auction for a bottle of 1947 Cheval Blanc quite rightly wants to know it’s the real deal. But when smaller sums of money are involved, people may shop knowingly, even ironically, as I did in ancient Byblos that day.

When I read about the work of the expert fake spotters that follow on these pages, I was struck most by the admission of Koyaana Redstar, a buyer at a pre-loved luxury website, who once had to tell the children of a woman who’d died that her entire collection of luxe handbags was fake. Redstar suspected their mother had bought them knowing this “and loved them anyway”. Not everyone is the victim of a dupe. Sometimes, they’re willing accomplices.

And perhaps such collusion increasingly suits the times. We’re told again and again to be authentic. Phoniness is posited as a major reason why, among other things, Kamala Harris lost the US election. But this is complicated territory. In the age of Instagram, the more “authentic” a person is, the more likely it is that they’re playing us, their every line rehearsed, their very wrinkles – “no filters!” – part of an elaborate game. I can’t say how much this matters to other people, but it does to me, which may be why I’m increasingly a sucker for fakes that are the polar opposite of subtle. Pah! to my tasteful little fossil. A friend of mine who used to live in a big house with very high ceilings hung laser-printed copies of a Francis Bacon triptych – three rather twisted portraits of Lucian Freud – on his walls, and they fairly took the breath away: ersatz, maybe, but thrilling in every degree nonetheless.

Here, five specialists in their field reveal the telltale signs they look for when identifying a fake.

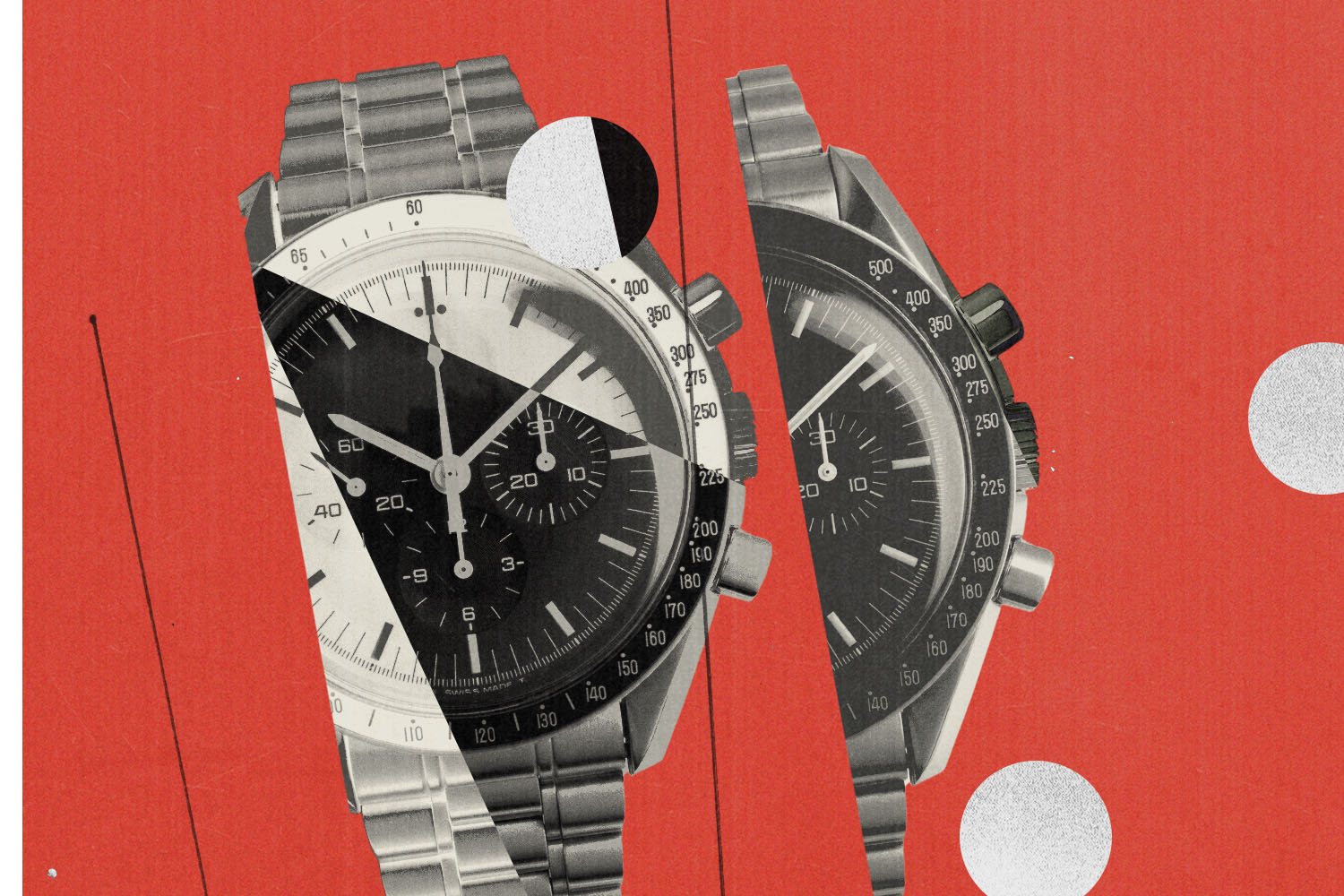

The watch expert

Marya Ali, watch expert at Love Luxury, a pre-loved luxury retailer in Knightsbridge

When I authenticate watches, the first thing I look at is the serial number and the quality of the engraving. The second thing I consider is the weight (although recently counterfeiters have been getting the weight spot-on) and then the colour of the dial. Counterfeiters find it difficult to get this right, because they are not using 18ct gold.

Related articles:

Then, I turn the crown on the side of the watch and listen to the watch winding. A watch might look good, but if the mechanism isn’t smooth, that’s a telltale sign of a fake.

I’ll also remove a link off the watch strap and analyse it in detail, including the screws. It should be well-crafted and so, perfectly easy to put the link back.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The box can also indicate if a watch is genuine, because why would you have a genuine watch with a fake box? And a fake box is much easier to spot, just by smell and touch. A real box is usually made of leather. On the inside, it will be suede or wood, depending on the brand. It should smell of the workshop. If it smells gluey or feels like plastic, it’s fake.

I’ll also look at the watch’s paperwork, such as its card or certificate: 60% of the value is the watch, and 40% is the card, because the card is like a logbook for a car. Some cards have a microchip and the brand’s logo shows up under a UV light.

Most fake watches I see are counterfeits of newer models, which are in higher demand than vintage watches. They’re targeted at young people, who are easier to scam than collectors.

I spotted a fake platinum Rolex recently, where they had used real platinum in the watch. The dial was also real and the weight was accurate. Everything else – the case, the card, the crown, the box – was fake. That watch probably cost about £7,500 to make. From far away, it looked like a genuine £80,000 watch.

I used to feel good when I spotted a fake, but now it makes me sad. It means my client has fallen victim to a scammer – and I’m the one who has to break it to them.

The fake poetry sleuth

Ira Lightman, poet

I’ve become known in the poetry world for spotting fake poems. What I detect tends to be a whole poem that’s been tinkered with, which the writer presents as their own. They might change place names, switch a word like “mother” to “father” or swap a few synonyms. But it’s the shape and form of someone else’s original work.

These writers don’t have a great emotional range, and I sometimes feel very sorry for them. For example, they might take someone else’s poem about a miscarriage and use all the metaphors, images and rhythm of that poem to write about stubbing their toe. It’s extremely immature work.

When editors ask me to look into someone, I’ll read up on the writer’s previous body of work. I’ve read tens of thousands of poems. And just as musicians can hear the key change in a piece of music, I know when a poet has mastered enough technical control to say what they want with pretty much any synonym they want to use, to be both sincere and beautifully ornate. If everything else a poet has written is flabby – if there’s no muscle, shape or choreography to it – and there’s one poem that is unusually skilful, that’s compressed, neat and tightly phrased, that makes me suspect they are borrowing from another poet.

I am relentless. I’ll look for the little touches in the poem that are just too good and vary the relevant phrase a bit – swap “a” for “the”, “our” for “your” in a Google search. I’m very persistent, like a dog with a bone. When I find the original poem, I see how cleverly it has been changed: just enough that it couldn’t easily be detected by dumping the whole work into Google. But the traces, the brush strokes of the original poem are still there.

On occasion, I’ve driven hundreds of miles to a library where my research has led me to believe I can find the original poem in an obscure magazine. I really enjoy tracking these originals down and sharing my evidence of a writer’s unacknowledged borrowing on my social media accounts, although I don’t think the people who do this deserve to be treated like they are immoral war criminals. They might be nice people. But they’re almost always terrible poets.

The handbag hotshot

Koyaana Redstar, head of luxury buying at Luxe du Jour, a pre-loved luxury website

I can usually spot a fake designer handbag in less than five minutes. The first thing I do is smell it. If it smells of chemicals or too leathery, I know it’s not authentic.

Then I’ll look at the hardware: the colouring of the clasps, the chain, the rivets, the plaques. Luxury companies will use really well-plated hardware, even gold. Fakes have a green undertone because they’re using cheaper metal. And if I’m looking at a Chanel or an Hermès, I should never see a Phillips screw, ever.

If I’m looking at the hardware on a Chanel or an Hermès bag, I should never see a Phillips screw, ever

If I’m looking at the hardware on a Chanel or an Hermès bag, I should never see a Phillips screw, ever

I’ll also look at the shape and material. Are the proportions correct? Does it look aligned and properly centred? Then I’ll hold the bag in my hands and ask myself: does this weight feel right? Is the leather the correct texture? Is the lining a cheap, polyester version of the real thing?

A lot of brands have serial codes and dates inside. So I’ll look at those – I know the Chanel, Louis Vuitton and Hermès fonts very well – and check whether the codes denote the correct country and date range. I’ll then listen to the sound of the lock turning in the bag and the chain clinking against itself – does it sound hollow or weighty?

Sometimes, to detect what’s called a “super fake”, you need to use an XRF machine which tells you the breakdown of the metals within the hardware. But personally, I’ve only come across two super fakes in my life that I was unable to detect without an XRF machine.

I process 1,200 to 1,400 bags a year and typically at least 10% to 15% of them are fakes. Counterfeiters tend to focus on new bags, because the latest collections are so popular and the price point so high.

I once had to tell the children of a woman who had recently passed away that her entire collection of bags was fake. I suspect she bought them knowing this, and loved using them anyway, but her family had no idea. It was hard not to feel like I was giving them news that would change the way they viewed their dead mother. I felt bad about that. But at the same time, I take a lot of pride in my ability to educate people about fake bags. It’s astonishing how often these bags are given to women as gifts. Then the victim will say to me: “I’m so glad I broke up with him.”

The whisky wizard

Dr Graham Bruce, physicist at the University of St Andrews

Very old bottles of whisky have sold for more than £2m. But bottles which are that expensive are devalued when you open them to test a sample and check they are authentic. So for the last 15 years, my colleagues and I have been developing new techniques to identify counterfeit alcohol without unsealing the bottle.

We shine a ring of laser light into the drink that we want to characterise and the molecules in the liquid will scatter the light and produce lots of different colours. These exact colours, which are not perceptible to the human eye, can be mapped using our cutting-edge techniques and used to generate a unique fingerprint for the chemical composition of the drink.

This chemical fingerprint can be used to authenticate a bottle of whisky, by drawing similarities with the chemical fingerprints of other bottles from the same producer at similar time periods and stating our confidence level that it would be genuine.

We can detect the oakiness of the cask and how peaty and smoky the whisky is, because these flavours are embedded in the chemical profile of the liquid. Using lots of data and machine-learning approaches, we can even distinguish between whisky bottles where the chemical differences are very subtle – for example, an 18-year-old versus a 12-year-old of the same brand, or a mixture of two slightly different blends from the same manufacturer. We can also use the fingerprints to do quality control by identifying potentially poisonous chemicals, such as methanol, or proving to a manufacturer that a sealed bottle has been tampered with at an early stage in the supply chain.

At the moment, our systems are lab-based so we’re bidding for the funding to develop a prototype we can use in a real environment. It’s been estimated that UK businesses lose £200m a year due to counterfeit alcohol and about 25% of the world’s alcoholic drinks are believed to be illicit and potentially dangerous.

Ultimately, we envisage the technology could be miniaturised enough to go under every bar and used to test the chemical composition of your drink, so you could potentially check it for the presence of methanol or date-rape drugs. We also hope that the technology will lead to consumer confidence that the expensive bottle of whisky you are buying is worth every penny – and you don’t have to waste a drop to prove it.

The ancient papyrus authority

Dr Roberta Mazza, associate professor of papyrology at the University of Bologna

I am an expert at identifying papyrus that is around 2,000 years old. A well-preserved papyri with a special text written on it – say, a newly discovered poem by Sappho – can be worth millions if it is allowed to be sold legally. However, genuine smuggled artefacts are also sold illegally online for as little as $200, as are forgeries.

To identify which is which, I’ll read the text to see if it makes sense in the language it is written in. Next, I will look at the quality of the papyrus. If it is modern, it is often rougher, brighter and the shape of it is regular. We expect ancient paper to have very irregular shapes, because they have been torn, and we expect to see holes in the writing, which would not have existed when the papyrus was made.

Sometimes a forgery is written on an ancient piece of papyrus that was cut from another fragment. So at first sight, the quality of the paper is right. But then you see they have written around a hole – which would have been created after the writing – or ended the text at the border of the paper, which makes it too regular.

Trembling, unsure handwriting is another giveaway. It’s not the confident, practised hand of a scribe living and doing their job in antiquity. It’s somebody copying some other text they have seen on the internet. I also look at the colour of the ink. Again modern ink is brighter and doesn’t have the patina it should have.

Ancient papyri can sometimes smell really bad. They smell of the ground, where they were buried, or the library where they were stored, while forgeries have a fresher and more chemical smell.

The next thing I’ll analyse is the provenance of the papyrus. Where does it come from? If I don’t have the full story about how this artefact arrived at my desk from ancient Egypt, I suspect it is either a forgery or a smuggled antiquity.

If the papyrus passes all these tests, then we use radiocarbon analysis to test the age of the Cyperus papyrus plant fibres that ancient papyrus is made from. We also use a high-magnification microscope to analyse defects in the handwriting and its fluency, and non-invasive techniques, such as raman spectroscopy and X-ray fluorescence analysis, to identify the composition of the ink. Since we know what ancient ink is composed of, we can spot when a forger uses something anachronistic. But science alone cannot give us definitive answers. The expertise of papyrologists is needed as well. It is an endeavour where my colleagues and I work as a team.

Roberta Mazza’s BBC Radio 4 series Intrigue: Word of God is available to listen on Sounds. She is also the author of Stolen Fragments: Black Markets, Bad Faith and the Illicit Trade in Ancient Artefacts

Illustrations by Mark Harris