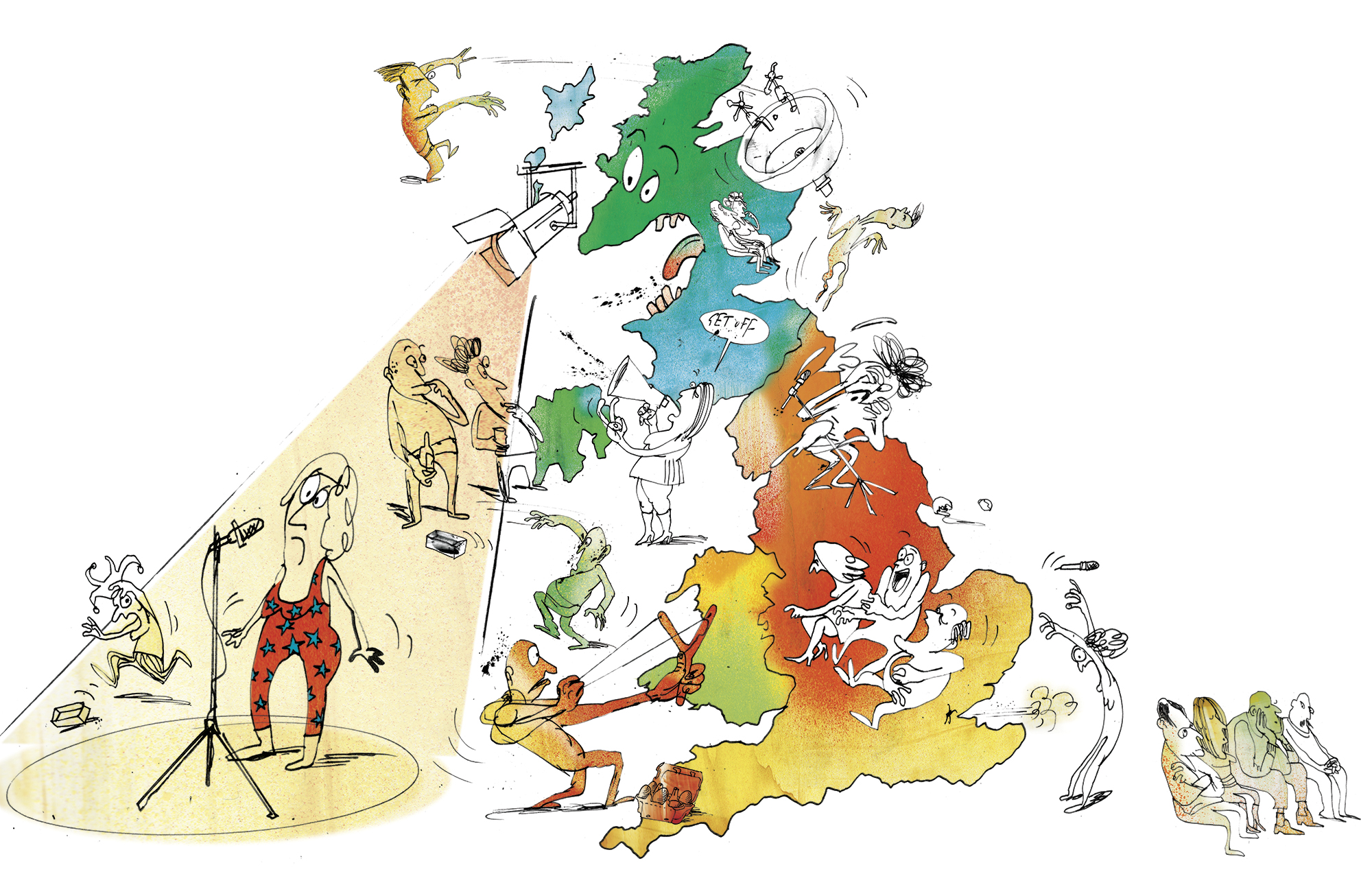

Illustrations by Simon Spilsbury

Debrett’s, whose new edition of Guide for the Modern Gentleman goes on sale this week, recently posted an online bulletin reminding well-bred theatregoers of things they should seek to avoid taking to a performance.

The list included such items as functioning mobile phones, whether muted or not, individually wrapped chocolates, and luggage.

There’s no mention of the full-sized can of fruit or vegetables which, historically, according to one actor I spoke to, represented such a well-known if occasional hazard when launched from the auditorium that performers were all familiar with the standard response of: “If you’re going to throw tomatoes, you could at least take them out of the tin.” (He told me that an incident I’d heard rumours about, concerning an actor who had made his entrance to be greeted by a full British standard 215mm house brick, was “very probably” apocryphal.)

That conversation took place on Merseyside. It’s a little trickier to imagine such an exchange occurring in Stratford-upon-Avon, say, or in Woking. There used to be a widespread assumption that audiences – somnolent and gentrified in the south of England – became progressively more animated as you headed northwards towards the so-called comedians’ graveyard, the Empire theatre in Sauchiehall Street, Glasgow.

The Empire closed in 1963.

Do areas still differ in the kind of welcome that they extend to visiting performers? It’s a question I began to ponder last autumn when I travelled on several legs of the UK and Irish tour by Elvis Costello, who is my main – well OK, my only – real friend in the music business. When the house lights come up to indicate the end of a show, Costello is fond of having the theatre PA play Where’s Me Shirt, a 1965 track by the late Ken Dodd. It’s a grotesquely memorable anthem which – while popular at the time, and a nod to Costello’s Liverpool roots – is only marginally less effective than CS gas in its ability to drive stragglers towards the exits.

Last autumn, after his show at the Regent theatre in Ipswich, the singer gave me a ride home to north London. We’d barely joined the A12 when the conversation turned to Ken Dodd. Around the time of 9/11, I spent a fortnight following Dodd on a tour that took in Eastbourne, Worthing, Llandudno, Wrexham, Skegness, Dudley and Whitley Bay. I was in New Brighton with our mutual friend, the playwright Alan Bleasdale, I told Costello, when the comedian eventually sat down to talk at length.

Related articles:

‘With my accent, some audiences presume you are thick’

‘With my accent, some audiences presume you are thick’

Johnny Vegas

At one point Dodd remarked that his famous routine concerning the “Giggle Map” – predicated on the notion that each town offers distinct challenges to an entertainer – was essentially a contrivance, unconnected in any meaningful way with the real world.

“Really?” Costello asked, “Are you sure that he meant that?”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Not entirely, I told him.

Regional differences were on the singer’s mind at that time. Since we first met in 1991, when he was orchestrating the soundtrack for Bleasdale’s drama GBH, I’ve covered a lot of miles with Costello, always on the understanding that any exchanges would not be for publication; the exception being one long interview in a hotel in Telluride. The experience of sitting him down with a recording device, I told the singer, felt rather uncomfortable; a bit like being forced to snog your grandmother.

“What an afternoon that was,” Costello said. “Poor Elsie. The startled cat. The shattered tea set.”

The singer’s tour in late 2024 had showcased stripped-down arrangements of his songs, performed with virtuoso keyboard player Steve Nieve. Ipswich had been welcoming and appreciative. Three nights earlier, he had brought the house down at the London Palladium with the help of the Brodsky Quartet, who collaborated on his 1993 tour de force, The Juliet Letters. A spectacular evening had begun with him saying to the audience, albeit in a playful tone: “I’m going to do the songs I do, and if you don’t like them, you can fuck off.” That remark was probably inspired by the memory that a week previously, at the Beacon in Bristol, 200 people – witnessing a similar set – had walked out, disappointed that they hadn’t seen the full band playing hits they knew, such as Watching the Detectives.

“Was it,” I asked, “something to do with Bristol?”

“No. It was to do with me. For not being Doctor Who, and able to travel back in time. We’ve had great nights in Bristol.”

There was a highly emotional night at the Olympia, Liverpool, earlier in the tour. Technical difficulties at the city’s Philharmonic Hall in 2022 had meant the singer had experienced one of the most difficult nights of his career. The sound problems had been so severe that one audience member, who I encountered in the gents, was shouting to a friend: “I know where he [Costello] is staying. I’m going to go there and sort him out” – a threat that he did attempt, unsuccessfully, to execute.

On his first return to the city, two years later, there was a point at the Olympia mid-set where, after the theatre had been in darkness for a minute or so, the singer appeared under a spotlight in the aisle a couple of yards away from where I was sitting with Bleasdale, put his hand on the playwright’s shoulder and sang a ballad rendition of I Can’t Stand Up for Falling Down.

“In that moment it was as though he took the city back,” said his close friend, the singer Ian Prowse. “There were people around him in tears.”

“I was aware of that,” I told him.

(“There can be times,” Ken Dodd had told me, in New Brighton 24 years earlier, when, as a performer, you find that you are suddenly taken over by something magic. It’s the only word for it. Something external takes over. It’s hard to explain. You’re out there, and it feeds you.”)

There’s no question that, in all live performance, most notably in standup, location is important. Perhaps the most remarkable collision in the history of light entertainment occurred in December 1961 when the comedian and civil rights activist Dick Gregory, the most important influence on Richard Pryor and Eddie Murphy among many others, who grew up in St Louis, was accidentally booked by the Playboy Club in Chicago to play to a convention of white businessmen. Fearing for his safety, the management tried and failed to block his path to the stage. It was a matter of moments before a refrigerator salesman had stood up and called him the N-word.

The comedian responded by saying that he was paid $50 compensation every time this happened, and urged the entire audience to get on their feet and call him that. Gregory added that he was about to open a restaurant of that name down the street: “So remember, every time you use that word, you’ll be advertising my place.”

A heckler told him to go back home. “The south?” Gregory responded. “I won’t even play the south of this room.”

Dick Gregory could have captivated any room in any city. The last time I saw him alive was when he was playing Washington DC, a couple of years before his funeral in Maryland in 2017. Before he went on stage, I mentioned a routine John Cooper Clarke does about Alzheimer’s, remembering too late that a civilian should never tell any comedian – let alone a legend – a joke. Gregory walked out on stage and opened with it. [“There are three advantages to Alzheimer’s. Number one: you can hide your own Easter eggs. Number two: you meet new people every day. Number three: you can hide your own Easter eggs.”]

The last thing I can remember Gregory asking me, at a dinner table after that show, where the guests included Malaak Shabazz, daughter of Malcolm X, was: “Who is that guy Clarke?” Great work travels.

But Gregory was a man who punched up, not down. I’m not sure what he would have made of Ricky Gervais’s routine, mocking a manual worker in Dunstable for the sin of mistaking him for Johnny Vegas. Or Michael McIntyre parodying – in a tone some might consider ungenerous – the local accent, when visiting an area on tour.

It’s the spiritual opposite of what Ken Dodd would have done – which was to discover, not by consulting the theatre staff, but by asking in local cafes, where the posh part of town was, in order to be perceived as being on the audience’s side. Billy Connolly had a similar generosity of spirit.

Playing Dublin once, Connolly said he was well received everywhere except Dundalk. “Where,” as he said, “their demeanour was: what kept you?”

The trouble with Dunstable, Sunderland or Lampeter, certain performers seem to be saying, is that such places are just not – what’s the word? – London.

What with increased geographical mobility and the popularity of binge-watchable drama (thanks to years of excellent work by Sally Wainwright and Sarah Lancashire, the briefest glimpse of a launderette in the Calder Valley appears to presage criminality in a way that was once restricted to low bars in the Bronx), the adjective “provincial” has virtually disappeared from common use.

We’re not quite there yet though, and the decision to have James Graham adapt Boys from the Blackstuff, Alan Bleasdale’s seminal 1982 television series chronicling the struggle of a group of Liverpool construction workers against the first wave of unemployment precipitated by Margaret Thatcher’s regime was, to say the least, audacious. Half the audience for the touring show would not have been born when the series was made; Graham was three months old when it was first broadcast.

Bleasdale says that Kevin Fearon, chief executive of Liverpool’s Royal Court, had been “calling me in the first week of January for years, suggesting a stage version of Boys from the Blackstuff. I’d always said, ‘I can’t do it, and I don’t know who possibly can.’ Then my agent, Stephen Durbridge, brokered a meeting between myself, the director Kate Wasserberg, and James.”

After which, James Graham says, “Kevin and Kate Wasserberg offered to put me and Alan together like pandas in a zoo, to see if we’d mate.”

The first read-through took place in a closed set in a small room at the National Theatre’s rehearsal centre near the Old Vic in Waterloo on a dismal night in December 2019. That early script was radically different from the production that drew ovations first at Liverpool’s Royal Court, then at the National (and opens in Leeds next week).

“The Liverpool audience,” says James Graham, “had a visceral connection to those characters. In London it felt as if many were meeting them for the first time. There’s a moment in the play where [benefit fraud investigator] Ms Sutcliffe says to her colleague: “Unemployment is a growth industry.” That line, the writer told me, was greeted with a laugh in London, and by silence in Liverpool – a city, Graham continued, where “unemployment is no laughing matter”.

Two months ago I travelled to see the current touring production in Bath. I’d anticipated that staging Boys from the Blackstuff at that city’s Theatre Royal would be a bit like holding a seminar on Jane Austen in the Gorbals. In the event, the house was hugely appreciative, and noticeably attentive to the writing. In Graham’s version, one of the most famous original scenes, between Yosser Hughes and the priest, which contains the line “I’m desperate, father”. [“Call me Dan”]. “I’m desperate, Dan” is not just replicated, but improved.

“Remember,” says the clergyman, “that, as a child of Christ, we do have free will. As Catholics we believe that we are, to an extent, responsible for our own choices.”

“Free will?” Hughes replies. “Like free markets? Those who are built to thrive and survive will? And those that don’t – sod ’em?” [Pause] “I knew it. God’s a Tory.” A line enthusiastically received, considering that Bath has not once in its history elected a Labour MP.

In theatrical touring, as opposed to comedy or music, Julie Walters told me, you are enabled by – or at the mercy of – the script.

“I only did it once, really,” said Walters, the original and definitive Angie in Bleasdale’s Boys from the Blackstuff. “It was a play called The Glad Hand by Snoo Wilson.”

The plot is of a kind that could trigger atrial fibrillation in the most phlegmatic of set designers.

“A South African tycoon sails an oil tanker to the Bermuda Triangle,” its precis begins, “hoping to evoke the antichrist, then kill him in a John Wayne style shootout.” When the play went to Warwick, Walters recalled, the locals “found it a bit bewildering”. (Having read Wilson’s piece myself, I’m with Warwick.)

The Glad Hand had gone down well in London, though. Some things do fare better in the capital. James Graham mentioned how Here You Come Again, the recent Dolly Parton musical “with a gay protagonist, did well in London. In some venues on the road, there were boos and ejections.”

At Boys from the Blackstuff in Bath, the first of Yosser Hughes’s headbutts drew a gasp from a woman in the stalls. And the room fell silent in the scene where Chrissie, having run out of food, shoots his pet goose dead.

“An audience comes with its own experience,” the actor Johnny Vegas told me. “I saw Boys from the Blackstuff at the Royal Court in Liverpool. There are those dining tables at the front of the stalls. Watching that scene, I was thinking, there are people observing this drinking wine and eating their dinner. My dad, when I was a kid, killed my pet rabbit and fed it to me. And gave me the paws as a souvenir.” For the audience, Vegas added, “it was high drama. For me, it was a memory.”

One London-based reviewer observed that it could be hard to tell the Liverpudlian protagonists apart.

“That’s a person,” Vegas said, “who shouldn’t be allowed near a theatre with a keyboard.”

The first time he and I spent any serious time together was in New York in 2001, where Vegas delivered a superb set to 12 people at Carolines on Broadway. In those days he had a picture of Ken Dodd on his travel bag (“Ken goes everywhere with me”), but had met him only once, when backstage for his autograph. Dodd – who later became an ardent convert to Vegas’s work – initially told him he needed “to do something about that voice”.

(These days, Vegas is focused on his artwork: Metamorphosis, an exhibition of his sculpture, opened last week at Liverpool’s Walker Art Gallery.)

Has Vegas come round to loving London?

“Even now,” he said, “with my accent, some people presume you are thick.” At first, in the 90s, he said, he found the clubs “very difficult. They all wanted the same thing. Like, ‘Have you noticed how dogs are different from cats?’”

Things changed when he played Up the Creek, the establishment run by the late Malcolm Hardee, whose infamous Tunnel Club closed in the late 80s.

“The first night I went on,” Vegas recalled, “a guy arrived on a racing bike, hammered. He came up to me and said one word: ****. Then fell asleep. I didn’t even have time to respond. Malcolm took the guy’s hat off, urinated in it, woke the cyclist and said, ‘Here you are: you dropped your helmet.’ At which point I thought, I have found my home in London.”

When Jerry Sadowitz played Montreal, he famously began with the greeting: “Hallo Moosefuckers,” and went on, “The trouble with Canada is that half of you speak French and the other half let them” – at which point he was knocked unconscious.

When Jerry Sadowitz played Montreal, he famously began with the greeting: “Hallo Moosefuckers,” and went on, “The trouble with Canada is that half of you speak French and the other half let them” – at which point he was knocked unconscious.

Of course, you can precipitate trouble anywhere. When Jerry Sadowitz played Montreal, he famously began with the greeting: “Hallo Moosefuckers,” and went on, “The trouble with Canada is that half of you speak French and the other half let them” – at which point he was knocked unconscious.

That was in 1991. Since then, security at large venues has been considerably tightened. (That said, I was astonished by the fact that, when we went to Boys from the Blackstuff on its first night at the National, they admitted my son who, not having studied his Debrett’s as attentively as I would have liked, had been found to be carrying a backpack containing half a dozen raw eggs – not a level of tolerance you would expect on the door in Huddersfield or Clacton).

In smaller halls, especially where the crowd share an interest – sporting, political, or because it’s a corporate event – things can still get a little tricky. The last two occasions when I was nearly punched were both at comedy performances.

The most recent occurred at a show headlined by Jim Davidson, where I joined a discussion on multiculturalism with two fellow patrons at the Gaiety in Southsea. To be fair, if you go to one of those shows you know what to expect: period humour and old-school gags about Lenny Henry. You can’t help thinking that if Davidson finds Henry a troubling enough figure to satirise, it might be interesting to take him along to the Moth Club in Hackney, and watch one of Sharon Wanjohi’s monologues about the advantages of a lesbian lifestyle.

The other occasion was at the Stockport Plaza in 2014 where Ken Dodd paused mid-joke and said, “I wonder how many great talents have appeared here?” At which point I found myself shouting “23”, to which Dodd, whose hearing was not what it had been, responded: “I’m being heckled! In Stockport!” Other patrons in the circle turned on me, understandably making it clear what I could expect if I made any other unsolicited intervention.

To return to Elvis Costello’s original question: was Dodd really obsessed with monitoring regional idiosyncrasies?

“He would talk about certain places,” his widow, Lady Anne Dodd, told me last week, “such as Glasgow – ‘no long-winded stories; no football gags at the weekend’ – but in the thousand or so notebooks I have I’ve not yet found any specific reference on that subject. In his lifetime I never looked at them. He made me promise to burn them after he died. I’m glad I didn’t.”

Dodd certainly made notes on his performances, but Lady Anne told me this had more to do with recording moments of improvisation that it did with any postcode. Touring together, she told me, the couple visited “well over 350 theatres, on what he called his ‘Window Cleaner’s Round’.” The very fact of Dodd staying on stage well past 1am, in Weymouth or Morecambe, made locals feel special.

At one point in New Brighton, Alan Bleasdale told Dodd: “I love comedians. As a writer, you finish your work, come to the theatre and have a drink. Whereas you – like an actor – go out there naked.”

“I do not go out there naked,” Dodd replied. “I go out there armed to the bloody teeth.”

He indicated a metre-high stack of A4 notebooks. “Those,” he said, “are full of notes.”

My own sense was that, by that stage in his career, he didn’t need to carry those volumes around any more than Michael Phelps needed to pack water wings, and that his hefty library served as some a kind of touchstone.

One night, backstage in 2001, I told Anne Dodd that I thought the comedian looked unusually stressed. “This is the Liverpool Empire,” she said. “This city is very important to him.”

In the conversations I had with Dodd, any reference to geography and character was confined to Merseyside.

“We have that spirit,” he said, “of playfulness. We are never stuck,” he said, turning to Alan Bleasdale, “for a bloody answer. Liverpool isn’t just a place: it’s a way of looking at life.” A pause. “I sometimes find myself wondering where that attitude stops,” he said. The border, he added, could run through adjoining semi-detached houses, “somewhere near Prescot”.

I was surprised that the comedian bonded so swiftly with Bleasdale, given the public support Dodd once gave to the Conservative party. (“Never again,” his widow told me, is what the comedian said about that, towards the end of his life. “Never again.”)

There had been a moment in that dressing-room in New Brighton, where Dodd embarked on a nostalgic eulogy to his comedy heroes: Laurel and Hardy, Frank Randle and George Formby. Then, I reminded Lady Dodd, he’d paused and delivered a remark I’d heard him make before. It had been something like: “Never talk about the good old days…”

“…because these are the good days,” she said. “Now. When you are alive. And walking. And breathing. And warm. These are the good days.”

Seven touring comedians share their highs, lows and weirdest moments

The good

An extraordinary comedian called Rob Rouse hosts a series of gigs in villages across the Peak District. That could go very wrong, very The Hills Have Eyes, but it was the opposite. The people we played to seemed really grateful that something was on other than bingo in their village hall on a Tuesday once a month. Jessica Fostekew

Last year, I was doing a gig at Monkey Barrel in Edinburgh and they had a power cut near the end of the show. It became my favourite gig because the audience was so on board. Everyone got out their phones and were lighting me with their torches. If that was in a swanky London theatre, I think people would have wanted their money back. Amy Gledhill

There’s a really special gig that happens in Cardiff called the Queer Emporium where they get loads of people to sit in an alley – which, to be fair, lots of people in Cardiff are doing anyway. It’s a really lovely queer gig, very nerdy and cool, and an example that comedy can happen anywhere. Sophie Duker

The bad

The first time I did the Comedy Store in 2017 I was dressed like a prototypical Russell Brand, wearing leather everything. From the second I walked out, I’d lost them. I had definitely mistaken how cool that outfit was. I scored 11 out of 10 for silence. Jordan Gray

My worst experience performing comedy came at Foxhills golf club in Surrey about 10 years ago, at the Ray Wilkins Charity Golf Day. Ray, a friend of my dad’s, asked if I’d perform. Apparently Omid Djalili struggling there the year before didn’t put my proud dad off. I followed a popular silk-jacketed lounge singer, in a tent full of ex-footballers, managers, and old rich people. I opened with some unwelcome Ray Wilkins material, then jokes about cheese on pizza in Bulgaria. The next day, Ray’s organiser rang. I told him not to worry about paying me. “Oh, there’s no way you’re getting paid,” he said. Tom Rosenthal

A few years back, at Jongleurs in Nottingham, I was booked on a night where there was a hen do and a stag do at the same time. I came on third and they were doing their singalongs and having a laugh and it was almost like I was interrupting their night. The stag do started booing me. I’ve never been back. Eddie Kadi

The bizarre

About eight years ago I was doing a sober gig in Manchester for people in recovery. The woman who ran the show insisted on emceeing herself, even though she wasn’t a comedian. She did the Beyoncé Crazy in Love dance and put her back out. Eventually we got her in another room and phoned an ambulance. Then, midway through my set, the paramedics came in and pulled her out on a gurney. I just carried on and didn’t address it, which I think made it even worse. Josh Jones As told to Killian Fox

Tickets for Jessica Fostekew’s new Edinburgh fringe and touring show go on sale on Friday. The second series of Amy Gledhill’s podcast Single Ladies in Your Area is out 9 May. Tickets for Sophie Duker’s new show are on sale now. Jordan Gray’s latest show is at the Soho theatre from 19 to 31 May. Tom Rosenthal’s new show opens at the Edinburgh fringe on 30 July. Eddie Kadi’s debut UK tour begins in Leeds on 6 September and runs until 24 October. Josh Jones tours the UK and Ireland from 4 September