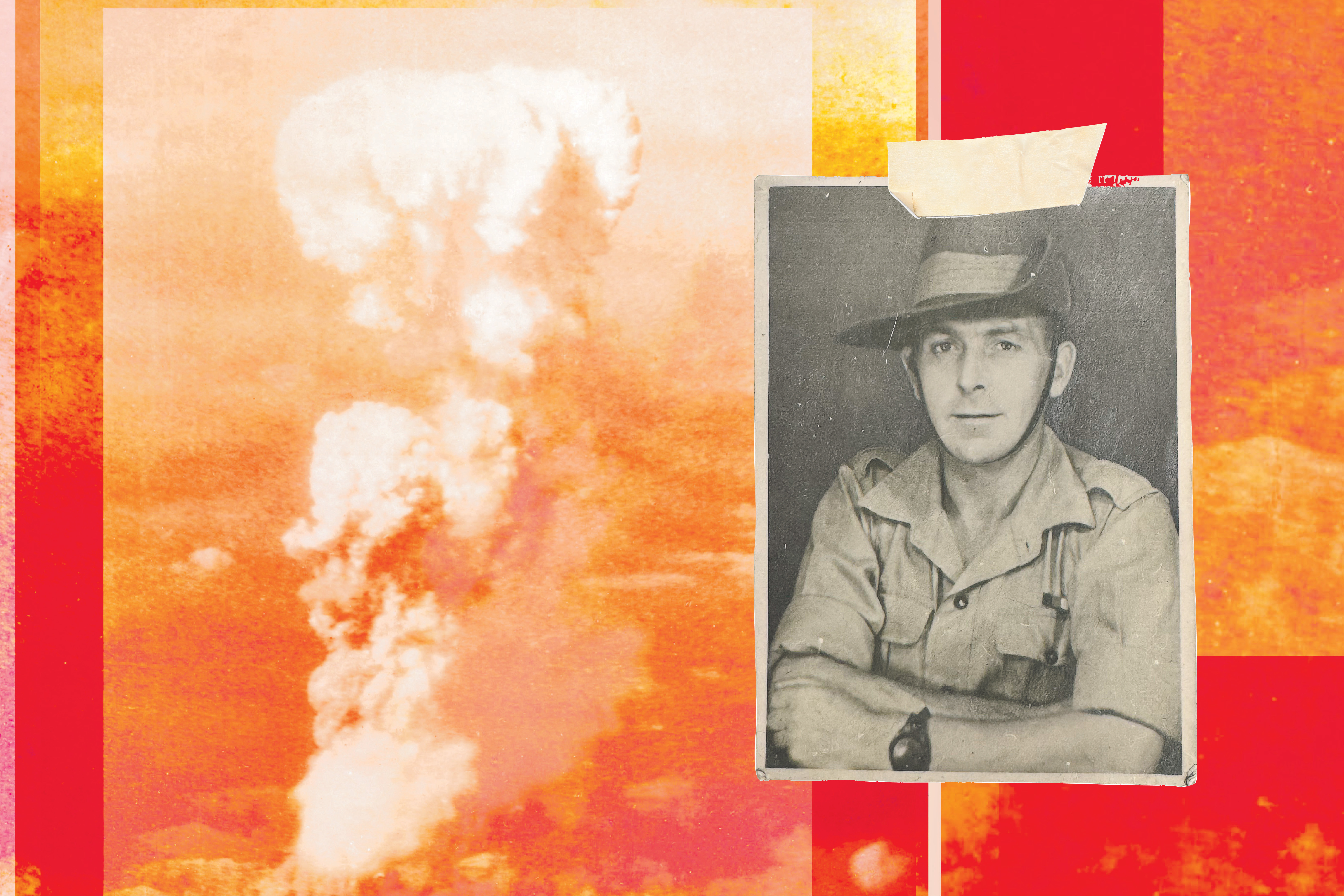

It was one of the most dramatic moments of my father-in-law’s lengthy military service in Burma. Captain Marcus Mitchell, a company commander in the East Surrey Regiment, was given the task of telling troops in August 1945 that a single atomic bomb had just destroyed the city of Hiroshima. This revelation was followed days later with news that Nagasaki had suffered a similar fate. Japan was suing for peace. The war was over.

Understandably, the soldiers were overjoyed. They would no longer be involved in an invasion of Japan that had seemed inevitable only a few days earlier. At the same time, the idea that a solitary device could destroy an entire city left them dumbfounded.

“They simply couldn’t envisage an explosion of such a scale and destructiveness,” Marcus later recalled. “To be fair, I had difficulty with the idea as well. At the same time, we all realised the bomb might have prevented thousands of allied deaths, including our own.”

It was a view shared by many others, including my own father. Thomas McKie also served in Burma, as a private. He rarely spoke about his experiences, a common trait among those who had served in the 14th Army – or “Forgotten Army”, as it came to be known, because its soldiers had to fight on in Burma in summer 1945 while Britain was celebrating victory in Europe. However, Dad did admit he thought the atom bomb might well have allowed him a peaceful, relatively early return to Scotland.

Capt Mitchell and Private McKie never met. My father was a working-class Glaswegian, who died in his sixties. After the war, his only goal was to try to lead a quiet life and avoid fuss of any kind, although his dry, acerbic humour is still remembered fondly by myself and my friends. “Do you not get fed at home?” he would ask startled pals I had brought back for dinner after school. Only his occasional nightmares, which filled our tenement flat with his terrifying shouts, hinted of some past horrors – though he resolutely refused to discuss what they might have been.

By contrast, my father-in-law was upper middle class and had a lovely, mellifluous accent. He was beautifully mannered and kind, and the idea that this gentle person could kill other humans seemed utterly improbable. Yet he clearly did. In his history of the Burma campaign, War Bush, author John AL Hamilton tells of Capt Mitchell, who – “having disentangled himself from his mosquito net just in time” – shot dead, at close quarters, a Japanese soldier who had broken into his camp.

Private Thomas McKie, top left, in India before serving in Burma

These were two very different men in background, class, education and social standing. Yet they were united by war, survived a conflict that could easily have ended in a far bloodier culmination and went on to meet the loves of their lives, with whom they then raised families. It could even be argued that the existence of my wife, Sarah, and myself can be traced to their wartime survival and, in turn, to the decision to build and drop atomic bombs 80 years ago, the first on 6 August 1945.

So should I be grateful for one of the most terrifying acts of warfare ever carried out? The answer is an emphatic no. Although as the anniversary of the bombings approaches, the need to understand the decisions that led to the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki has never been more urgent. Why were civilian targets chosen? How many died and over how many decades? And did A-bombs actually end the war in the Pacific?

These issues still divide military commanders, historians and politicians, and at a time when more and more nations are developing nuclear weapons. Examining their deployment demands renewed, urgent consideration. The increasingly bellicose nuclear rhetoric of Vladimir Putin and Kim Jong-un, and the attacks on Iran, suggest we may be losing sight of the terrible lessons of Hiroshima.

Today there are only a handful of hibakusha – as the survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are known – who are alive and who can share their testimonies of the terror that was unleashed over their heads in August 1945. Theirs is a slowly diminishing voice that speaks of the dreadful consequences of using nuclear weapons.

Several of the books that are being published to mark the anniversary, and to explore once again the ethics of that terrible choice, suggest that the fates of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were sealed by June 1945, when the US finally captured Okinawa, the smallest of Japan’s five main islands and the only one invaded during the second world war. That 82-day campaign claimed the lives of a quarter of a million people, including 110,000 Japanese troops who, almost to a man, refused to surrender.

The fanaticism of the Japanese soldiers who defended Okinawa and the massed kamikaze attacks that were launched on US troops undoubtedly shocked military chiefs. A far greater death toll would clearly be inflicted during further invasions, which would certainly have involved British soldiers, sailors and airmen.

Captain Marcus Mitchell, Robin McKie’s father-in-law, with his wife Sue in 1952

As Saul David states in his new history of the Pacific war, Devil Dogs: “President Truman’s decision to authorise the use of the atom bomb was directly influenced by the bloodbath on Okinawa.”

Harry Truman’s views were shared by Winston Churchill, who believed the conquest of Japan could cost the lives of up to a million American and half a million British troops. Then Churchill learned about the success of the Trinity atom bomb test explosion in New Mexico in mid-July 1945. “Now all this nightmare picture had vanished,” he wrote later. “In its place was the vision of the end of the whole war in one or two violent shocks.”

US air chiefs were also becoming increasingly receptive to attacks on urban targets. They once criticised Britain for abandoning precision aerial attacks in Europe in favour of “area-bombing” of cities but gradually changed their views. Carpet bombings became commonplace in the Pacific, culminating in the 10 March 1945 raid in which hundreds of B-29 bombers dropped thousands of bombs on Tokyo, killing more than 100,000 civilians. It was the most destructive single air attack in human history, with an initial death toll that surpassed those of Hiroshima or Nagasaki.

This change in strategy “not only permitted an asymmetric and deadly war against the Japanese urban population, which was contrary to previous air force doctrine, but also prepared the way for the apotheosis of indiscriminate destruction in the two atomic attacks in August 1945,” writes the British historian Richard Overy, in his book Rain of Ruin.

Thus it was on the morning of 6 August, a B-29 bomber – named Enola Gay, after the mother of its pilot, Col Paul Tibbets – took off from North Field on the Pacific island of Tinian and flew towards Hiroshima. In its hold it carried a single 3-metre-long, 4,400kg bomb called Little Boy that had been constructed by scientists working for the Manhattan Project, home of the first atomic bomb plant, in Los Alamos, New Mexico.

Six hours later, the Enola Gay reached Hiroshima and Little Boy was released. After a 43-second descent, a cordite charge blasted together its uranium cores, which reached critical mass and exploded above the Shima surgical hospital. The Enola Gay – already miles away – was battered by the blast.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Tibbets looked back. “A giant purple mushroom ... had already risen to a height of 45,000ft, three miles above our own altitude, and was still boiling upward like something terribly alive ... and even though we were several miles away, it gave the appearance of something that was about to engulf us,” he recalled. His co-pilot, Capt Robert Lewis, was more succinct. “My God, what have we done?” he scrawled in his logbook. It was a grimly pertinent question, for on the ground, the effect of the blast was cataclysmic. A blinding flash followed by a massive roar and shock wave flattened the inner city and engulfed it in flames. People were incinerated or flung through walls and across streets. Within minutes, nine out of 10 people within half a mile of ground zero were dead. Small fires broke out across Hiroshima and soon merged into a single firestorm that eventually engulfed more than 4 sq miles of the city. Howard Kakita was a boy when the explosion hit his grandfather’s house and he and his brother ran for safety. “When we got to the road, there were lots of people, many severely injured with injuries that you could not believe,” he recalled. “People with such terrible burns that their skin would be dripping from their body. Some had guts hanging out from their tummy, holding on.”

Worse was to come. Days after the blast, as the world struggled to comprehend the enormity of the A-bomb attacks, survivors began to notice strange effects. Huge clumps fell out of people’s hair when they brushed it; those who had escaped burns or injuries began to succumb to malaise, weariness and feverishness; wounds that had been healing abruptly began to widen and swell. Radiation sickness began to kill off survivors. “Doctors noticed strange similarities to those corpses they were dissecting: low white blood cell counts, unexplained internal bleeding, rotting gums, dramatic hair loss and damaged vital organs,” notes Ian MacGregor in The Hiroshima Men. In the end, thousands died slow deaths from vomiting, diarrhoea and bleeding from bowels, gums, nose and genitals.

Military authorities tried hard to downplay these horrific tales. Gen Leslie Groves, director of the Manhattan Project that had built the atom bombs, was asked about the effect of intense radiation on humans. “As I understand it from the doctors, it is a very pleasant way to die,” he replied. The full, disgraceful nature of this lie was exposed within a year, when journalist John Hersey’s account of the bomb’s horrific aftermath, Hiroshima, was published in 1946 and revealed a population that was suffering grotesque illness and disfigurement long after the bomb had exploded.

Western leaders’ reactions to the atom bombs’ impacts are disturbing enough. However, there remains a key issue that continues to vex historians. Did dropping them actually shorten the war?

At first glance, the timetable looks compelling. Hiroshima was destroyed on 6 August, then Nagasaki on 9 August. A day later, Japan sued for peace. However, this schedule misses out one key event. On 8 August, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan. Until then, Japan’s leaders had hoped the Soviets would act as a neutral third party in negotiating peace with the US, a dream that was destroyed when one and a half million well-armed troops poured into Japanese-held Manchuria and advanced at a rate of about 43 miles a day.

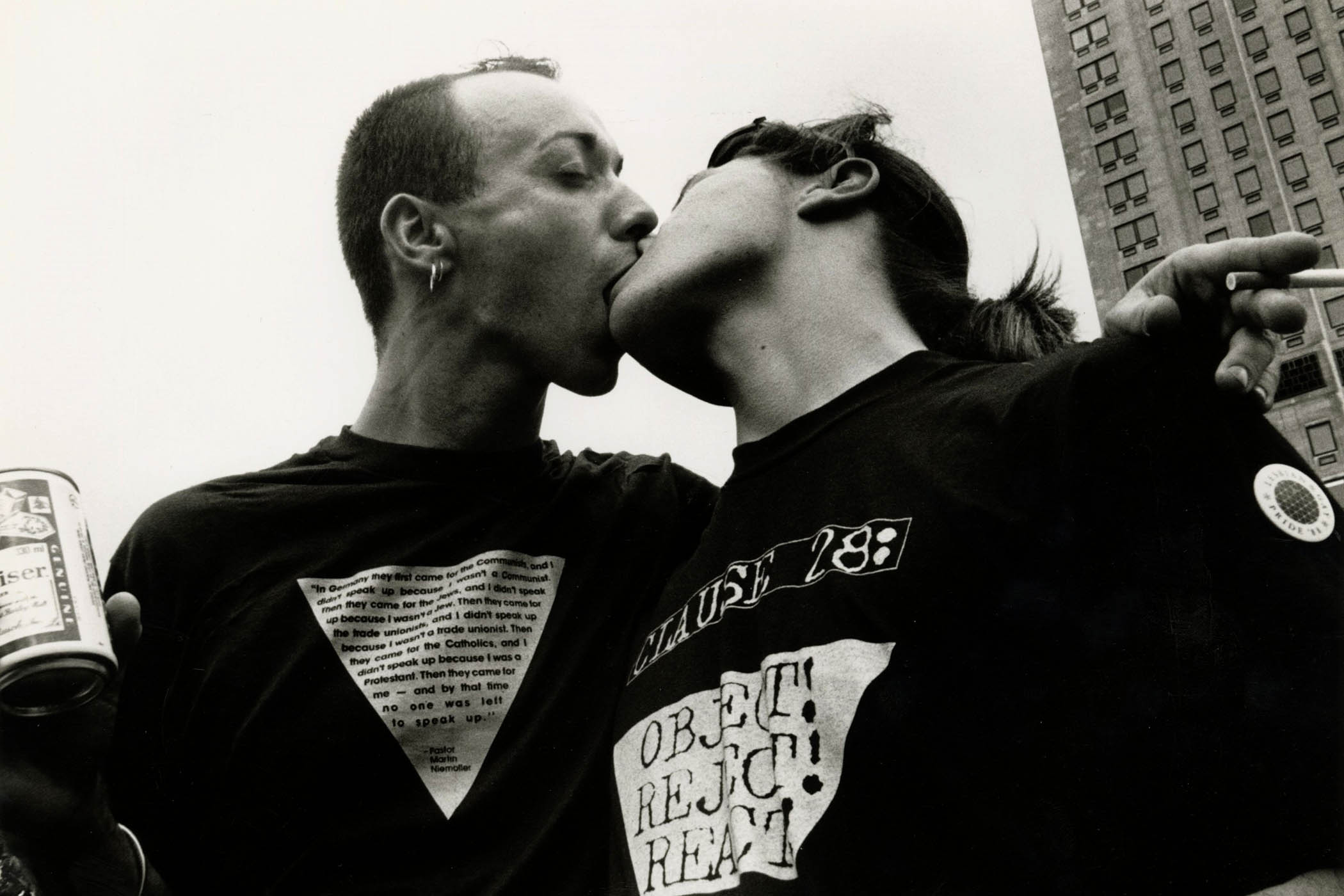

British forces in Burma circa 1945

“The Soviet invasion was a shock because it brought suddenly very near … the possibility of Soviet invasion and occupation before the Americans arrived,” notes Overy. For Japan’s far-right leaders, the prospect of a communist takeover was a fate that could not be contemplated. From this perspective, the atom bomb appears to have been only one element in the mixture of factors that led Japan to surrender, and clearly undermines any notion it was the single source in the saving of the lives of so many allied soldiers, including Capt Mitchell and Pte McKie. The moral calculus of war is complex.

“If atomic bombs are to be added as new weapons to the arsenals of a warring world, or to the arsenals of nations preparing for war, then the time will come when mankind will curse the names of Los Alamos and of Hiroshima,” admitted Robert Oppenheimer, the scientific leader of the Manhattan Project.

The writer George MacDonald Fraser – creator of the Flashman novels – who fought as a private in Burma, took a very different view, however. If Japan had not surrendered and he had to go on fighting, he would have had, he argued, a one-in-four chance of dying in battle. Had that happened, his three children and eight grandchildren would never have been born. “And that, I’m afraid, is where all discussion of pros and cons evaporates and becomes meaningless, because for those 11 lives I would pull the plug on the whole Japanese nation and not even blink,” he declared in Quartered Safe Out Here, his recollection of the war in Burma.

Like many other allied troops, Fraser had developed a distinct hatred of the Japanese military, whose treatment of prisoners and local people was often shocking. These issues are explored in more exacting detail in Question 7, Richard Flanagan’s part-history of the atom bomb and part-memoir of his own family’s fate. In 1945, his father was a prisoner of war who had already survived several years working on the infamous Burma “death railway”, which had cost the lives of more than 12,000 captured troops (as well as 90,000 conscripted civilians). “It was widely expected that those surviving PoWs would be mass murdered on invasion, or at best, used as human shields,” Flanagan states.

The atom bomb might certainly have helped to save their lives, and in that context could be seen as the lesser evil: a quarter of a million civilian deaths versus the lives of more than a million soldiers.

However, Flanagan insists, it could never be right simply to see this as an argument in favour of the bombing of Hiroshima. He writes: “Tragedy exerts its hold upon our imaginations because it reminds us that justice is an illusion. Hiroshima is the great tragedy of our age from which we continue to seek understanding and yet can never understand.”

Photographs courtesy of Robin McKie/Getty Images