It was the bicentennial year, 1976, the celebration of the Revolution. We were touring Horses, riding straight into the future. It was a freewheeling time, hanging out with William Burroughs at his bunker on the Bowery, watching Television at CBGB, plotting a chaotic future with my brother Todd, and crossing America with a rock’n’roll band. Our country had its great failings, the shame of Vietnam, racial injustice, and sexual discrimination. But we revelled in America’s cultural contributions. Rock’n’roll, jazz, activism, abstract expressionism, the Beats. It was a time when I felt my own power and believed in our mission.

Touring Horses along the west coast, the band – Lenny Kaye on guitar, Jay Dee Daugherty on drums, Ivan Král on bass guitar and Richard Sohl on keyboards – were accompanied by Paul Getty, and the French actor Maria Schneider. Maria, much adored for her performances in The Passenger and Last Tango in Paris, with intense black eyes and a mass of unruly dark hair, was a mirror in a white shirt and black tie. Paul was the grandson of one of the richest oil magnates in the world and the victim of a famously botched kidnap in Italy. William Burroughs had introduced him to me, a pale acolyte, the youngest passing through his portal of saints. I was quite fond of Paul with his wild red hair, freckled skin, and eyes like mine, slightly cast. William had asked me to keep an eye on him, which was virtually impossible, for Paul was brilliant, intuitive, and reckless. We found like-minded people in San Francisco then spent a few riotous nights playing the Roxy in Los Angeles. Paul, Maria and I must have appeared in a curious triangle during the band’s stay in West Hollywood at the Tropicana Motel. We all loved it there, it was cheap, gritty, and had seen all kinds of action since the days the Doors recorded LA Woman just across the highway.

On 9 March 1976, we kissed Maria goodbye and boarded a plane for our first concerts in the midwest. I wore a black pleated silk dress that Paul had bought me at Bendel’s. It was the same dress that Sylvia Kristel wore in the film Emmanuelle, only hers was cream. It became my uniform, a $500 dress I paired with my black Horses jacket and combat boots.

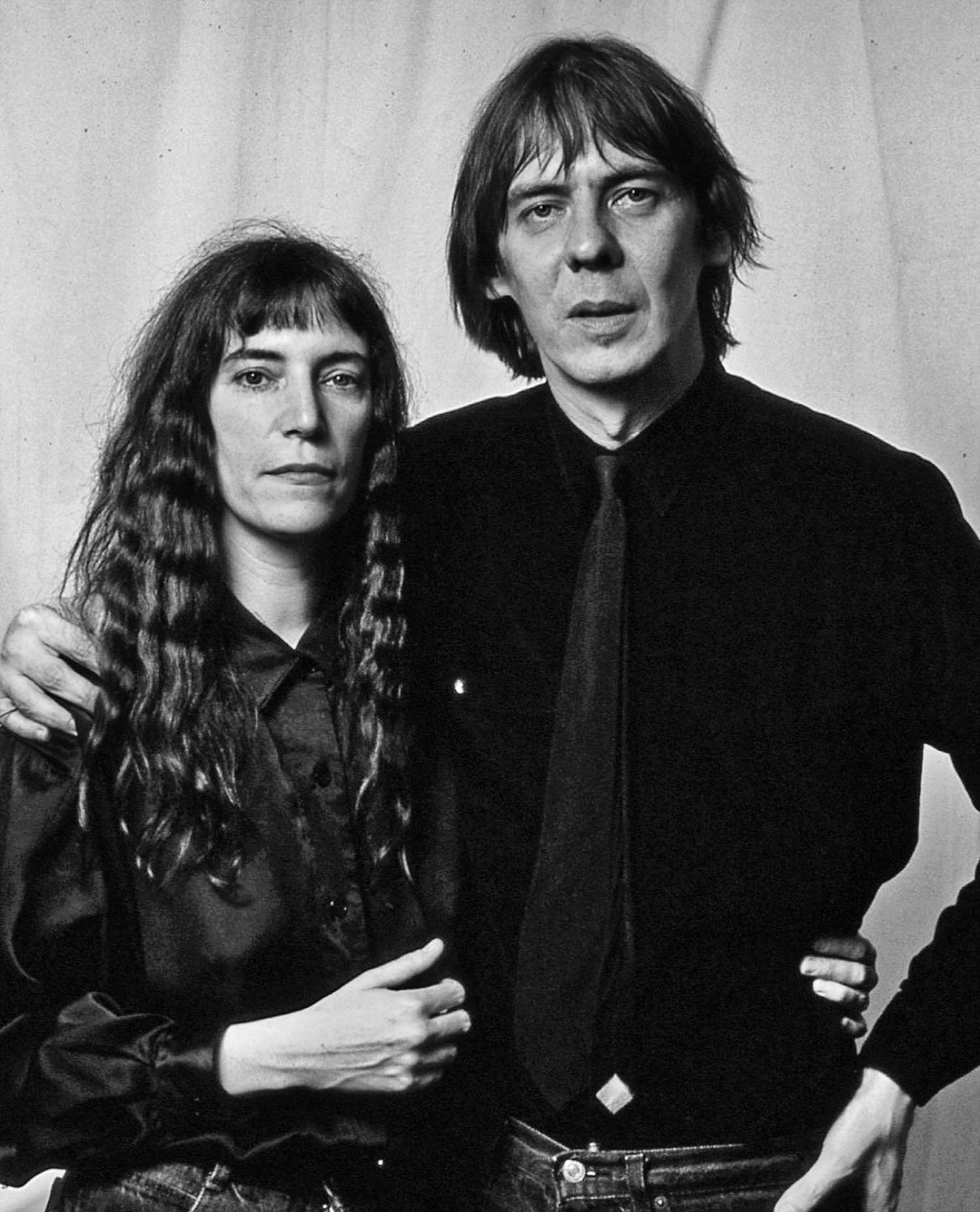

Patti Smith with her husband, MC5 guitarist Fred ‘Sonic’ Smith

We landed in Detroit on a windy Tuesday afternoon and went straight to a welcome party hosted by the Detroit musician community at Lafayette Coney Island. I didn’t particularly like parties, but I was lured by their legendary hot dogs. The people were very welcoming. We stayed awhile, had their deservedly lauded hot dogs, said goodbye to all, and headed toward the door. That’s when I first saw him. He stood by a white radiator in a blue overcoat. I noticed the threads where a button was missing. That fleeting moment was to redirect the whole of my life. Lenny introduced us simply: Fred Smith Patti Smith, Patti Smith Fred Smith. He had lank brown hair and eyes like water. He placed the button in my hand, and I wordlessly declared it a treasure. I felt a gravitational force; my being truly shaken, kindling my desire for the One, the better savage. Fate had touched us; I knew at that moment he was the one I would marry.

Soon after we checked into the hotel, Paul gathered his things and bid me farewell. When I asked him why he was leaving he looked straight into me and said you and that guy are meant to be together. I feebly answered that I didn’t even know him but truthfully could hardly protest. He smiled as he left, Paul with his pale freckled skin, one ear, and long tangle of red hair, a fallen clairvoyant archangel.

Fred “Sonic” Smith was born in West Virginia in his grandfather’s kitchen. His small and feisty grandfather, once a coal miner, delivered him because the midwife was unable to get there in time. Fred’s mother was intensely religious. His father was a rough and ready teamster who knew every Hank Williams song. Good natured and hard-working, he had harbored a mean streak; father and son often physically clashed from the time Fred was a boy.

In high school Fred was extremely athletic. His boxing coach was impressed with his defensive agility and long reach. But privately aware of his suppressed rage, Fred bowed out, fearing he might hurt someone. He was also scouted by the Tigers’ farm team because of his tremendous throwing arm. He was overjoyed but conflicted, for at the same time he was co-forming the band that was to become the revolutionary MC5. At 16 he fled from home, school, sports, and the draft. Wielding his guitar as his weapon, Fred’s conflicting emotions dominated his playing. When we first met, I had no idea who he was, but I knew instantly he would be my life. Such is the terrible mystery of love, that draws us from all that we know.

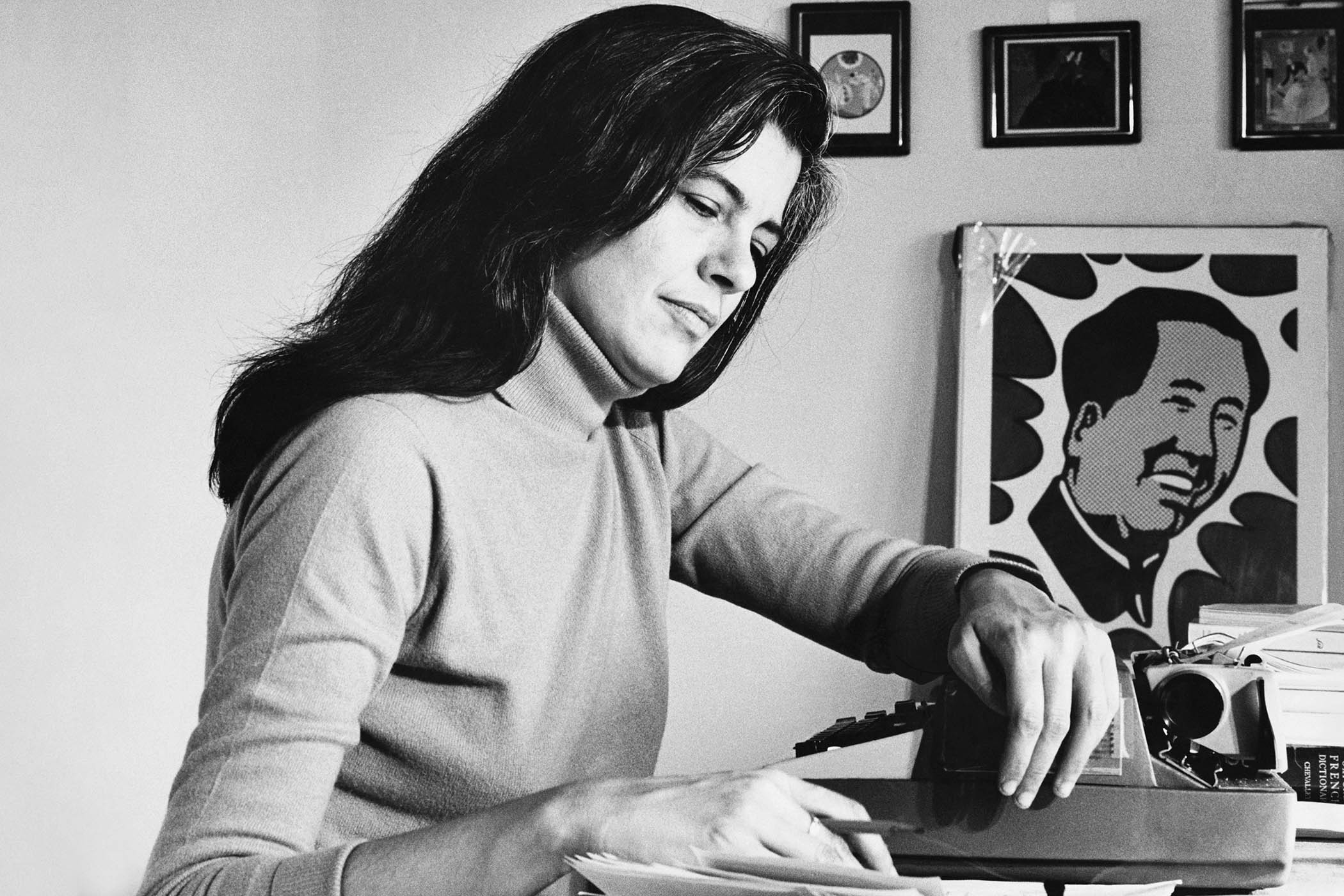

Patti Smith photographed in Los Angeles, 1974

I didn’t see him again until December, after our second concert in Detroit. Our band and crew joined local musicians at the bar in the Renaissance hotel. Fred took my hand, and we slipped away, entered the scenic glass and steel elevator, and he pressed the 25th floor. Those moments in the slow-rise elevator were our first alone together, and I can still recall the intense beating of my heart. With the panorama of the Motor City growing distant below, our far-off courtship began, one that would depend more on trust and patience than actual presence. Letters, telepathic wishes, and occasional phone calls at a time when long-distance calling was prohibitively expensive. On tour in some obscure town spying a phone booth, I would pocket everyone’s change, stop our tour bus by the side of a road, and call, even for a few minutes, just to hear his voice.

Related articles:

Though it kept us apart, the opportunity to tour the world was a blessing for the penniless traveller. So many pages from Around the World in 1,000 Pictures turning. Yet nothing had prepared us for the response of the young in Brussels, London, Paris, Amsterdam, Germany, all over Europe. Lenny and I spent as much time as possible talking with kids that gathered outside our hotels, in the streets, or standing in line before a concert. We answered their questions, encouraging them to start their own bands. We happily collided with known and yet unknown members of rising new bands: Siouxsie Sioux, members of the Slits and the Clash.

Sonic’s Rendezvous Band were touring on the other side of the world. Fred and I saw each other when we could; in the early days of our courtship I would fly to Detroit, even for two days to be together. The closer we got the more he seemed to test my faith in him. When we left his car to have tires changed, we took a brief walk along the highway. He stopped and held out his hand. Do you trust me, he asked. Yes, I said, taking his hand as he led me halfway across the road. I let him take me in his arms, closed my eyes, and waltzed with him. Even as the traffic intensified, we continued to dance unharmed on the median. At an abandoned reservoir we navigated a stony path in the available moonlight. Looking up, Fred raised his hands toward the stars and seemed to rearrange them, bringing them closer, and turning them in his hands. These moments felt like hours, yet were mere seconds, our minds as one. We did not speak of them; we lived them. Fred could be abstract, futuristic, with the hands of a musician, a mathematician, a magician.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

More than ever my writing life was usurped, living fiercely in the present, tour upon tour, a physical external time when the writer deferred to the performer, the pen to the electric guitar. For a time, I lost contact with language; my Fender Duo-Sonic spoke for me, moaning and screeching feedback in place of words. I felt somewhat conflicted at the sight of my journals, containing little else save scattered lyrics and abandoned letters to Fred. Rimbaud had proclaimed himself scourge and seer, advancing then intentionally shooting himself in the foot, then walking upright. My feet were riddled with imaginary holes. I felt a walking contradiction negotiating a desire to stand still yet compelled to race into the future. My brother Todd was always by my side. Throughout childhood, he stepped back allowing me to take on the roles of hero, general, king, always being the dedicated first soldier, first knight.

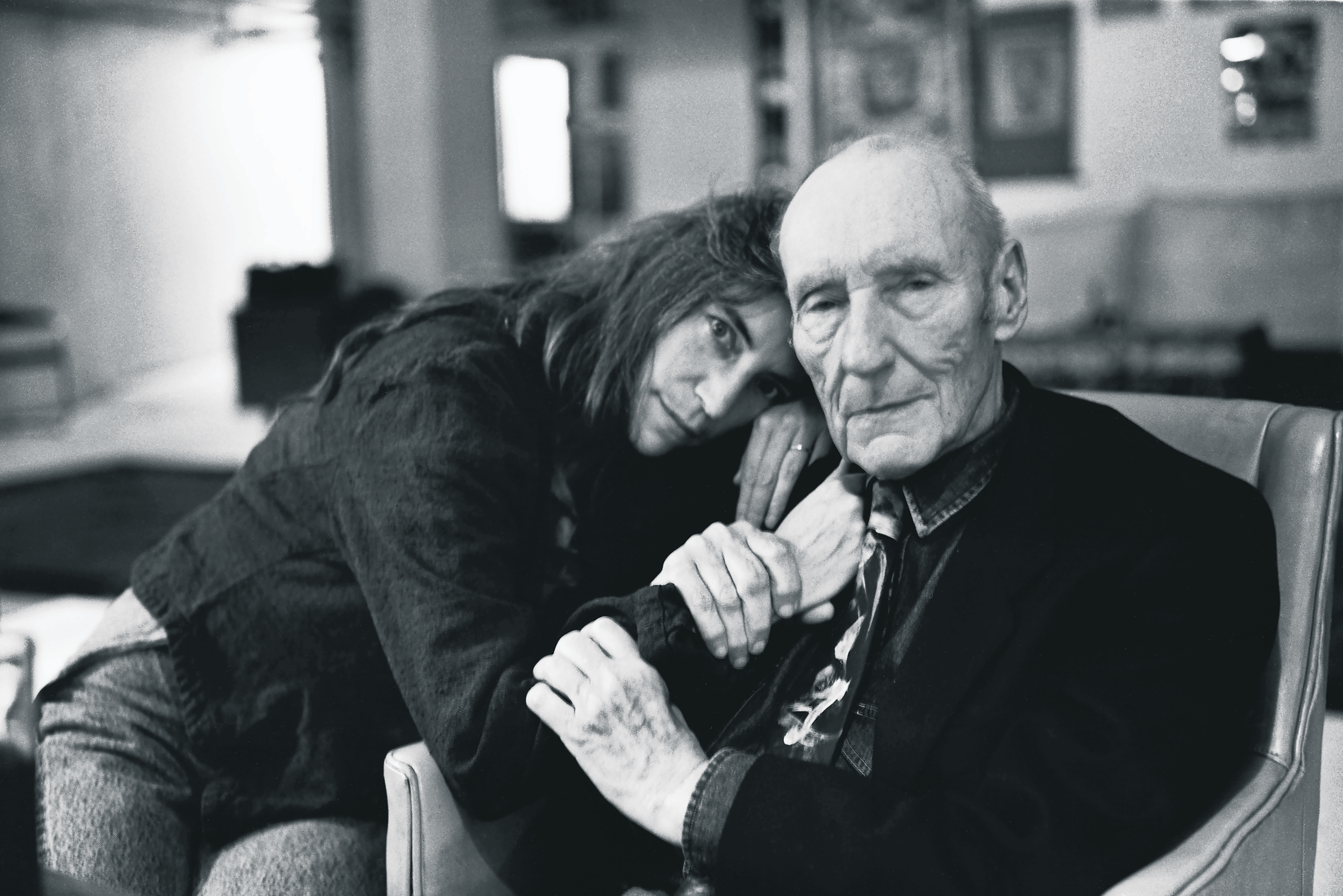

With the writer William Burroughs, 1995

In between tours, we were called to take a break and make another record. Struggling to write lyrics for another album I laid out the things that were on my mind: famine in Ethiopia, the fate of a boxer, Rimbaud in Abyssinia, and the sonic language of the electric guitar. I received a letter from a girl named Andi Ostrowe, who had read that we were about to record Radio Ethiopia. She had recently returned from the Peace Corps serving in a southern rural village in Ethiopia. We met up and talked of the current revolution, the deposing of Haile Selassie, the destructive military coup, and the city of Harar where Rimbaud had been a coffee trader. She was small and sincere with dark hair and dark eyes. I was moved by her pictures and keepsakes from the country I had yearned to journey to and promised to invite her to the studio.

I chose Jack Douglas to produce the album believing he was a good match for both sides of the band’s personality. We could be unrestrained and at times incomprehensible yet benefited by Ivan’s relatable song structures: Ask the Angels was written for a thriving network of kids off the grid with a special nod to the youth of Los Angeles. The reggae inspired Ain’t It Strange was a confrontational invitation to an impossible dance. The emotional Pissing in a River swerved from referencing the past to interrogating the future. The greatest challenge was our title track, which I envisioned as entirely improvisational, primarily driven by Lenny’s churning riff then veering into the seemingly unattainable. I urged the band to take the impassioned risks I so admired in the work of [the jazz saxophonists] Albert Ayler and Ornette Coleman. We made a few passes but not satisfied we all agreed to wait and try again.

On 9 August, Jack grounded us as a hurricane was fast approaching New York City. I paced the floor like a hemmed-in coyote feeling the effects of both the coming storm and the full moon and was swept by a premonition that we would get the title track that night. I called Jack and after a short standoff he headed to the city during the first throes of Hurricane Belle. Todd rounded up the band and I packed my Duo-Sonic, called Andi, and we all met at the Record Plant. Jack wedged towels under the control room doors in case the heavy rains caused flooding. At midnight, the deluge peaked, we plunged together into the well of our most ambitious undertaking. I had no words, just a mental map of the sufferings of a people, the death rattle of one of our greatest poets, and the desire for us to unleash a torrent of our own. By three in the morning four inches of rain had come down flooding the streets, high winds had knocked over trees and power lines, and we had successfully added to nature’s chaotic touchdown. Twelve minutes of propelling distortion, Jay Dee’s thundering drums and splashing cymbals, Ivan’s pumping bass, and as my whining Fender Duo-Sonic drew altruistic swords with the mournful wailings of Lenny’s Stratocaster, Richard Sohl introduced an unexpected melodic shift creating the melancholic beauty of Abyssinia.

With her Leica, the photographer Judy Linn shot the image of me in a dark silk raincoat and my hair in a ponytail for the cover. She perfectly captured my frame of mind and the gritty atmosphere of our practice room. In solidarity with the band, I added “group” to my name. Andi lent her pictures for the album insert and was soon hired as Todd’s technical assistant, a welcome addition to our small and loyal crew.

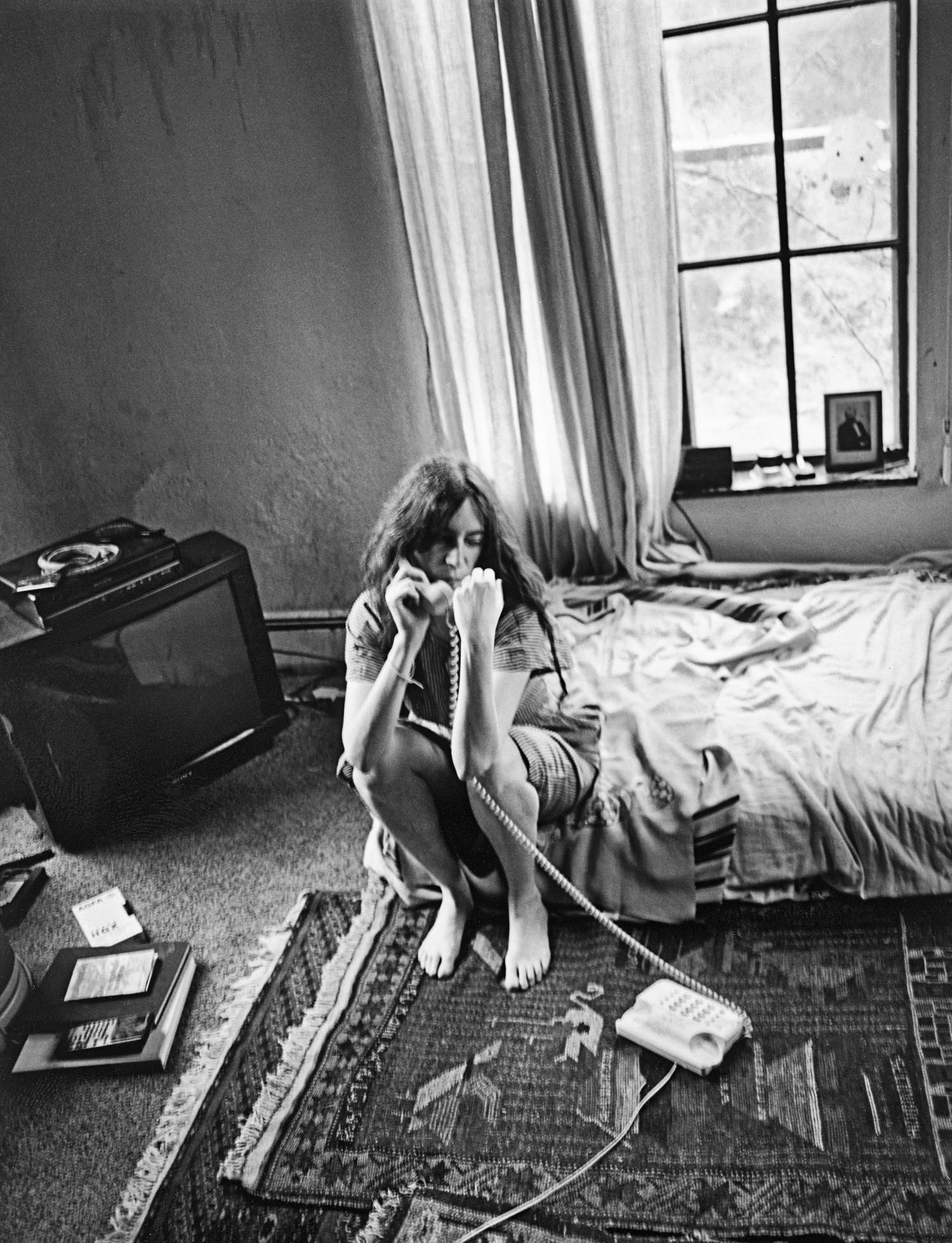

Patti Smith, 1995

Radio Ethiopia, released nearly a year after Horses, was not well received and the title track I was so proud of was deemed unlistenable. Some of our former champions accused us of selling out and Jack Douglas was picked apart, blamed for supposedly changing our direction. We were energetically evolving, and I was certainly no pawn. Jack drew from us what we had desired and were intent on giving, flawed and unruly as we were. Compounding all woes Pissing in a River was surprisingly chosen as a single. I was requested to change the lyric to swimming or wading in the river. I hadn’t considered that the word pissing would cause such a stir, but would not change the lyric, and it received only limited bleeped airplay.

There were arrows everywhere, but I took it in stride, rallying our camp with a message from the liner notes: The art emerging from the boundless scope of rock’n’roll needs no other patron but the people. With that in mind we plunged back into touring. One of the most memorable concerts was in Spain. The former fascist regime had denied two things from Spanish culture: Picasso’s Guernica and rock’n’roll. With the death of Franco, Picasso’s masterpiece, his response to the horrors of war, was installed in Madrid. And on Rimbaud’s birthday we were flown from Paris to Barcelona for a makeshift concert. We used whatever equipment was on hand, and that night we all danced in celebration, spawning a lifelong kinship with the Spanish people.

In December we returned to the States and played the Tower theater in Upper Darby, not far from Rambo Terrace where we had stayed with our contentious Aunt Gloria in 1949. I could see my mother, who thrived on the energy of our concerts, in the front row surrounded by her own adoring fans. As Lenny’s downstrokes introduced the continually amending misadventures of Johnny, I caught sight of wide stretches of the American plain. Wild horses with lightning bolts tattooed on each ear raced through the dust as we segued into Gloria. As I left the theater with my mother a horde of kids surrounded me with albums to sign. It was cold, and I felt wired and exhausted and wanted to keep going. My mother was incensed that I would walk away from them. You sign every album, she demanded, don’t forget who put you here.

This is an edited extract from Bread of Angels: A Memoir by Patti Smith (Bloomsbury, £25). Order a copy from observershop.co.uk for £22.50. Delivery charges may apply

Photographs by David Gahr/Suzan Carson/Michael Ochs Archive/Getty Images/Seiji Matsumoto/Steven Sebring/Allen Ginsberg