Photographs by Fabiola Cedillo

If you stand on the walls of Jimena de la Frontera’s 8th-century Moorish fortress in Cádiz and squint down through the hazy autumn sunshine into the cluster of white-walled houses, you can just about make out the red, yellow and purple tricolour of the Second Spanish Republic (1931-39) flapping violently in the breeze. The flag is attached to a humble building, the Casa de la Memoria La Sauceda – the House of Memory – an oasis of remembrance for the uncountable victims of Francoist repression, killed in the Spanish civil war and the dictatorship that followed.

The Casa de la Memoria is a museum, a research archive, a lending library, an events space and the hub for a volunteer-run organisation that has helped lead the charge against forgetting in Spain. It is open to the public six days a week – one more day than Jimena’s town hall, which is located four doors down and flies the country’s more familiar red-yellow-red monarchist flag.

Given that the Spanish government’s conservative estimate counts a minimum of 114,000 civilians killed and thrown into unmarked mass graves, you would assume every small town such as Jimena (population: 6,800) would contain a similar building. Yet the Casa de la Memoria, which opened in 2016, stands almost entirely alone. Perhaps the most surprising thing is that the house exists at all; it only does so thanks to years of tireless efforts by local grassroots memory campaigners, and bequests and civilian donations.

Andalucía – historically disproportionately rural, poor and left wing – was the region most affected by Francoist violence, both during the 1936-39 war, and in the subsequent reign of “white terror”: the torture and extrajudicial killings meted out after Franco’s victory. Official figures list at least 45,566 victims in 708 mass graves in Andalucía alone. Barely a tenth of these bodies have been excavated, exhumed, identified and reburied.

Cortijo El Marrufo, which served as a concentration camp, near La Sauceda

It is 50 years this week since Franco’s death. In that half-century, the Spanish political class has been slow to address the horrors of his dictatorship. Indeed, while so many of his compatriots’ remains lay bundled in unmarked graves, the body of Spain’s dictator, in effect, lay in state outside Madrid, beneath the largest crucifix in Europe – all the way up to 2019, when it was finally, awkwardly, relocated to a nearby cemetery.

When I visited the unabashedly totalitarian Valley of the Fallen in 2018, acolytes of Franco had left fresh flowers on the dictator’s grave. At his reburial, mass was said by Ramón Tejero, the son of Antonio Tejero, the civil guard officer who stormed the Spanish parliament in 1981 in an attempted military coup.

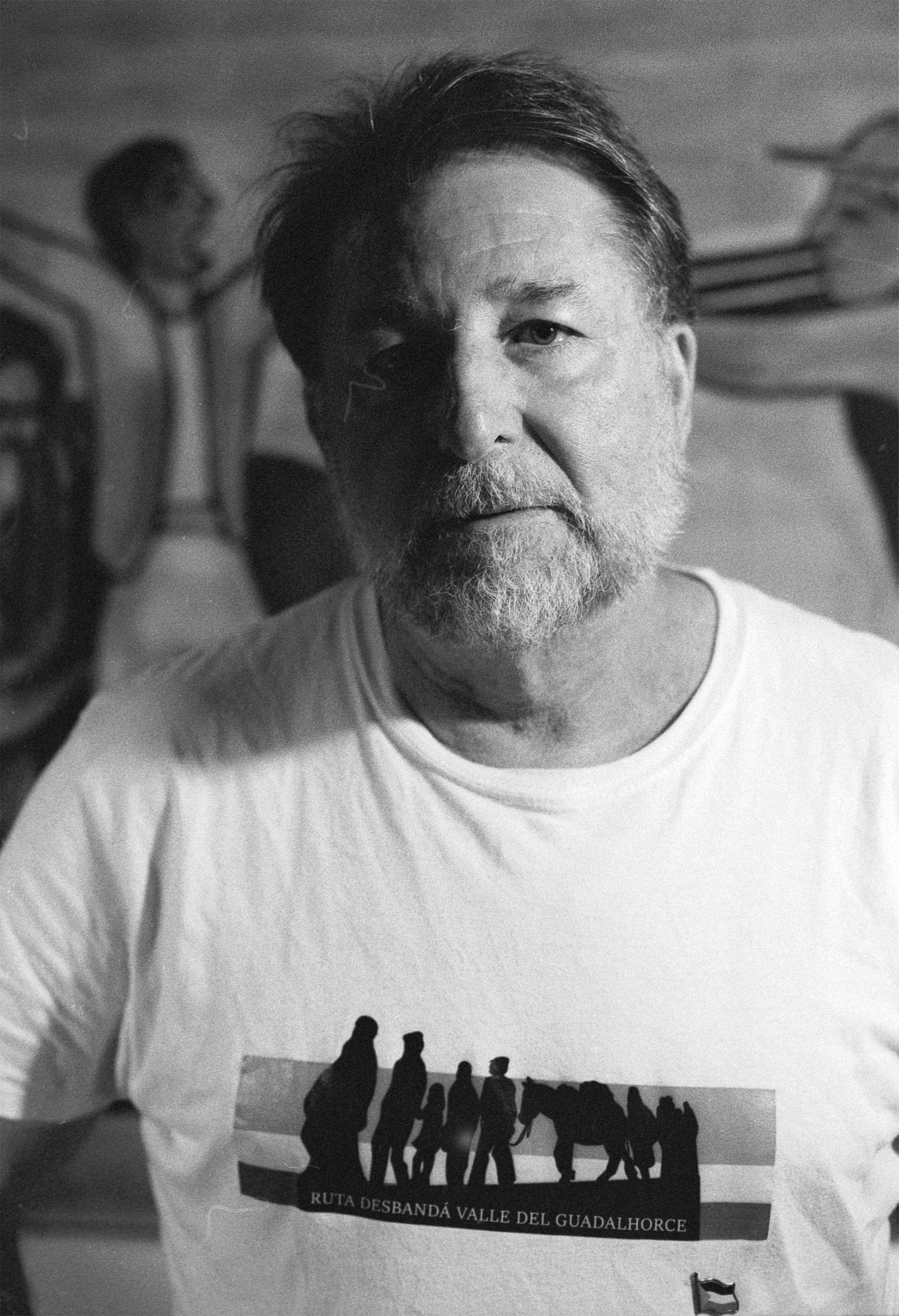

“Spain has a huge amount of unfinished business,” said Andrés Rebolledo Barreno, director of Jimena’s Casa de la Memoria, when we first sat around a table in January over black coffee and sweet almond cake. Rebolledo, a serious and quietly passionate man, wore a blue hoodie and a bracelet in the same red, yellow and purple tricolour as the republican flag. “We are just one house, in one small town – but it’s an emblematic town; a town where people resisted the coup d’etat and where truly terrible things took place as a result,” he told me. “And [now] people come to visit us from all over Spain to” – he paused – “to refresh their memory.”

Franco’s soldiers launched their military coup on 17 July 1936 from Spain’s north African exclaves and started to seize towns in the south one by one. On 28 September, after a bloody battle, Jimena was captured by soldiers loyal to the coup, Falangists and civil guards. Franco was formally announced head of state and the army by the nationalist side three days later. His chief strategist, Gen Emilio Mola, made their agenda abundantly clear: “eliminating without scruples or hesitation all those who do not think as we do”.

Andrés Rebolledo Barreno, director of the Casa de la Memoria La Sauceda

One important thing to understand about the Spanish civil war is that neither side really saw it as such. For the republicans, this was an illegal military coup against a democratically elected government. For the Francoist side, it was not a civil war, because the other side was not worthy of being part of the Spanish civitas. This was a holy crusade, or a war of liberation, as it was later described in schools under Franco: to liberate Spain from a conspiracy of communists, anarchists, atheists, freemasons, feminists, Jews, Muslims, democrats, liberals, homosexuals and foreigners, and their plot to undermine Spain’s intrinsic, historic, Christian greatness.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Within days of seizing Jimena, the nationalists put this crusader philosophy into practice. One of the first to be unscrupulously eliminated was Sebastián Conde Godino, a 15-year-old boy. Historians’ best guess as to his purported crimes are that he was playing with furnishings from the local church after it had been looted.

On 6 October 1936, along with three men, Godino was marched up to the fortress above the town to be executed. Before they could reach the top, at the grand arched entrance to the fortress, he began sobbing in desperation and crying out for his mother. The teenager fell to his knees, refusing to go any further. The Francoists shot him right then and there.

“Once you know stories like this,” said British-born Jimenan and Casa de la Memoria volunteer Debbie Eade, “it is hard to pass through that arch without thinking about the poor boy, pleading for his mother.” The four dead bodies were dumped into an unmarked mass grave in the cemetery at the top of the hill. Many other such “enemies of Spain” were also subsequently buried there, where they remained for more than 80 years.

It’s an emblematic town, where people resisted the coup d’etat and where terrible things took place

It’s an emblematic town, where people resisted the coup d’etat and where terrible things took place

Coordinated by the Casa de la Memoria, the site was finally excavated in 2020. Some of the volunteers who helped with the process of digging, dusting and cataloguing the bones they found were great-grandchildren of the victims. DNA swabs of saliva were taken from the descendants and samples of each were sent off to a laboratory in Granada.

“People from the village had given their DNA samples, but unfortunately they weren’t able to match most of them,” Eade said. “People had been waiting and waiting and hoping and hoping. We received these boxes that say ‘skeleton number 1’, ‘skeleton number 2’ and so on, but we can’t put names to them all.” Nonetheless, a proper burial ceremony followed, and a dedicated memorial to 79 named victims, killed between 1936 and 1947, now stands in the centre of the town’s cemetery.

Rebolledo’s own story is typical. Growing up, he longed to know what happened to his maternal grandfather, after whom he is named – all he had been told was that his grandfather had been shot and disappeared. He got involved in one of the local memory campaigns that sprang up after the founding of the Association for the Recovery of Historical Memory (ARMH) in 2000. “I’m here doing this for my family, for my mother, which is very personal,” Rebolledo said. “But we are also here for everyone; ordinary citizens filling a gap left by the authorities: attending to the human and social need to recover those remains, and to cure and heal that collective and social trauma. If trauma is not treated and healed, it persists.”

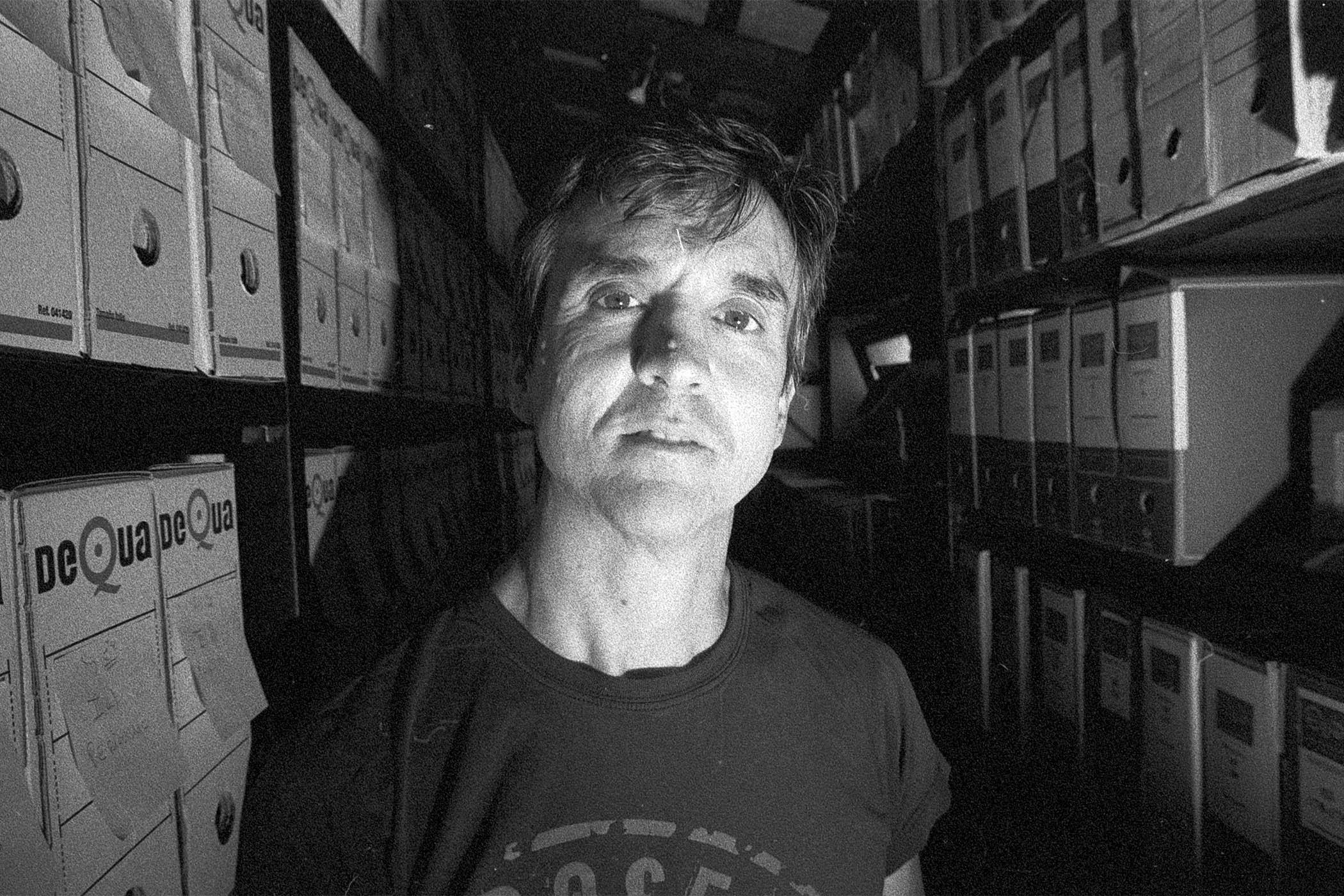

The archive contains about 7,000 (often rare or unique) books, pamphlets, old magazines, recent research reports and lever-arch files, including a substantial foreign-language section. Similarly, the Casa de la Memoria website is an almost overwhelming repository of information: photographs, databases, documents, interactive maps, videos, podcasts, news and reports of talks, book launches and media appearances – all of it produced by a small nucleus of volunteers.

The ruined chapel of La Sauceda is one of the few structures that remain standing after being bombed during Spain’s civil war

The town hall in Jimena is governed by the United Left, legatee of the once-powerful Spanish Communist party; you’d think it would be eager to support such a unique and successful project as the Casa de la Memoria – not least because it brings visitors, who stay for lunch in the town, or longer. But the state and the citizen-led historical memory movement have never really worked in harmony. The Casa de la Memoria only this year finally signed an agreement to collaborate with the town hall, about 10 paces up the road.

The Francoist violence was not limited to the tiny pueblo of Jimena, and nor is the Casa de la Memoria’s historical research. Indeed, it is named after La Sauceda, a wooded valley lined with cork oaks and buzzing with crickets, half an hour’s drive to the north of Jimena in the most remote part of Los Alcornocales natural park. These days, La Sauceda is a bucolic, off-grid site for eco-tourism, scattered with basic stone huts. Because it is so hard to access, it has historically been a refuge for bandits, smugglers and other rebels. During the civil war, it became the region’s final holdout for republicans escaping the advancing rebel troops.

Two white donkeys formed the bulk of the traffic on the winding hill roads from Jimena to La Sauceda. At the entrance, there was an Andalucían regional government sign stating that La Sauceda is a “place of historical memory” – but the plastic layer containing the explanatory text beneath had already faded, worn and torn, so that no detail remained of the horrors that occurred there.

When Franco’s forces came for La Sauceda, there were about 800 civilians hiding there, including Rebolledo’s mother, then a babe in arms, and his grandparents. Life was basic, but they pooled their resources, sharing livestock, a communal mill and bread oven, as well as a chapel, school and several shops. The rebel troops attacked La Sauceda on 31 October 1936 with ground forces after an aerial bombardment, massacring scores of people, looting and burning the homes, raping women and shaving their hair. “For us,” Rebolledo said, “La Sauceda is like our little Guernica. It’s a smaller town than Guernica, but the technique was the same. It was one of the first aerial bombings targeting civilians in the 20th century.” Some managed to flee, and Franco’s troops took every survivor they could to a nearby farm called El Marrufo, which became a concentration camp. That was the last that Rebolledo’s mother saw of her father or her uncle. Officially, they had simply disappeared.

Octavio Huertas Díaz visited Casa de la Memoria with his mother, María del Carmen Díaz García (top picture). His grandfather, Fernando, was a victim of Franco’s attacks

Testimonies from older local people pointed to the existence of mass graves at El Marrufo, and in 2010 volunteers began searching the site, using metal detectors to conduct a survey, looking for bullets. One Jimenan who had been just seven years old when the Francoists besieged La Sauceda took them to a small pile of stones that marked one of the graves. Under the guidance of a few anthropologists and archaeologists, a cast of volunteers and family members spent four months excavating what could be as many as seven mass graves there.

“Of the 28 bodies we were able to recover,” Rebolledo said, “seven were women, all with signs of violence, tied up with wire and thrown in the ground like dogs.” The bodies included both Rebolledo’s grandfather, Andrés, and his great-uncle, Antonio. Besides numerous bullet casings, and the wire used to tie victims’ hands before they were shot, they found tobacco pipes, buttons, a lighter, a pocket mirror and a pencil. The final personal effects of 28 lives whose deaths went unrecorded, if not forgotten, for three quarters of a century.

One of the people who heard about the El Marrufo excavations was the businessman Miguel Rodríguez, owner of Festina, a multinational watch brand – his grandfather had been executed by the Francoists there, just like Rebolledo’s. He helped to fund much of the rest of the work, and was one of several donors who helped to bring the Casa de la Memoria into being a few years later. Having been painstakingly excavated, exhumed and identified, the bodies were given proper burials. You could easily miss La Sauceda’s cemetery if you weren’t looking for it. Only a faded sign and a waist-high wooden gate, leading to a narrow gravel path that winds off into the trees, signals that you have arrived. Eventually, a small, white-walled enclosure emerges from the trees and a tiled mosaic reads: “Where lives and dreams were cut down, memory and justice return.” In the new “pantheon of dignity”, each grave has its own niche, including one for each of the unidentified victims – adorned with dried flowers and hand-painted epitaphs.

When the cemetery was inaugurated in December 2012, Rebolledo paid tribute to the tenacity and dignity of his fellow descendents. “We will continue working within our means to locate the remaining graves,” he said that day, “although we believe this task is the responsibility of the authorities, and it is sad that it is up to us, the families, to do it ourselves.”

Franco died not in a ditch but in bed, as a victor. His legacy is that justice would not be served

Franco died not in a ditch but in bed, as a victor. His legacy is that justice would not be served

There is now a fairly standard internationally agreed path for post-conflict societies, beginning with some form of truth and reconciliation commission. The problems Spain has now, Rebolledo believes, lie in the state’s failure to begin this work 50 years ago, in the febrile, violent years after Franco died: “All the work we began ourselves in the 2000s, it should have started with the government in the 70s and 80s,” he said. “Locating graves, carrying out exhumations, DNA tests, creating a DNA bank, dignified burial sites, eliminating all the Francoist symbolism – all the streets, squares, coats of arms and plaques.”

The amnesty law signed in 1977 by all main parties, including the PSOE (Socialist Workers’ party) and communists, was, many believe, a necessary pill to swallow, to ensure Spain became a democracy. Rebolledo accepts that, but remains exasperated at the way it has inhibited justice: “Franco died not in a ditch but in bed, as a victor, and he left behind this legacy: that justice would not to be served, that the amnesty law would be signed, that everyone would be pardoned and that his successors would sign up to a pact of silence – of forgetting.” Having determined that they would not be investigated or punished for any of their crimes, senior Francoists in the late 1970s discreetly destroyed their own archives – a final act of vandalism against Spanish history and humanity implicit in the supposed “pact of forgetting”. Since then, the stock response of the Spanish right to memory campaigners has become: “Don’t stir up the past.” Or: “Don’t open old wounds.”

Since the foundation of the ARMH in 2000, the issue of historical memory has been unavoidable for Spanish politicians. Two centre-left PSOE prime ministers have passed historical memory laws – José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero in 2007 and Pedro Sánchez in 2022 – requiring the renaming of Francoist streets and removal of monuments, tweaks to the school history curriculum and so on. But when Mariano Rajoy was elected prime minister for the conservative Partido Popular (PP) in 2011, he promptly announced that “not a single euro” would be spent excavating mass graves – instead, he explained, Spain must forget the past and “look to the future”. (Two years later, Rajoy managed to look backwards for long enough to rustle up €280,000 of government money to refurbish Franco’s mausoleum). When the PP won a historic and unprecedented election in historically “red” Andalucía in 2018, it likewise froze the excavation work being carried out, after pressure from its far-right coalition partner, Vox – refusing to spend money allocated by Madrid for this purpose.

Woodland near La Sauceda

It is often pointed out by memory campaigners that these excavations should not be regarded as archeological digs, but as crime scenes. But without amendments to the 1977 amnesty law, prosecutions are not even theoretically possible – it enshrined an equivalence between the people doing the torturing and extrajudicial killing, and those being tortured and killed. There were more than 45,000 forcibly disappeared people in Andalucía alone – and yet, as far as the state is concerned, no one forced them to disappear.

Sánchez’s 2022 democratic memory law made some useful advances, but is fairly toothless; tellingly, its text uses the word “victim” 1,442 times, but “perpetrator” not once. Even so, it was immediately challenged at a regional level. Rightwing parties in Valencia, Aragon, and Castile and León have either tabled or passed supposed “laws of concord”, rolling back the PSOE legislation.

And the drama and distractions have bled out from the political realm into pop culture. Last summer, the comedian Quequé (Héctor de Miguel) joked on his radio show that the Valley of the Fallen should be blown up, and the pieces used to “stone paedophile priests” – for which he was taken to court by an organisation called Christian Lawyers for having committed a “hate crime”. The case was dismissed in May.

Politics seems to obstruct memory at every turn. About 125 miles north of Jimena sits the Andalucían capital, Seville, home to both the regional government and Pico Reja, the largest mass grave in western Europe, containing the remains of 1,786 people. Its excavation was completed in 2023. When I visited in January, I hiked out to the little-visited back corner of Seville’s vast San Fernando cemetery, 20 minutes’ walk from the front gate. There, I found the recently erected memorial sinking back into the sand. A stretch of red safety tape flapped uselessly in the wind. I searched on my phone to find out what had happened, and found a regional news article about the local PP and PSOE fighting over whose fault it was.

A burial niche in La Sauceda’s cemetery

Nonetheless, Sánchez has declared 2025 a celebratory year of “50 years of liberty”, as a way of marking the anniversary of Franco’s death, without naming him – and the prime minister is finally applying pressure on regional governments to get digging and tackle the overwhelming majority of sites that still remain untouched. But excavations, exhumations and DNA testing are all expensive, requiring high levels of specialist technical support.

“One issue with identifying the bodies when so much time has passed is that bone remains deteriorate,” said Juanma Pizarro, the Casa de la Memoria’s archivist, as he leafed through recent acquisitions in fingerless gloves, including a Franco-era folder labelled “Register of dangerous people.” Furthermore, identification is becoming harder, as there are fewer direct relatives around to provide DNA samples. Moreover, a 21st-century European democracy leaving it to ordinary civilians to organise a full-scale archaeological dig, to try and recover the bones of their murdered grandparents, is about as ridiculous as it sounds.

“At no point,” Pizarro continued, “has the government said: ‘We’re going to make a national exhumation plan’ – the things we are doing here at the Casa, on a small scale, but with huge effort, a nation state can do perfectly well.” (In the absence of state action, Jimena has become an example to others. Late last year, another small Andalucían village, Alcalá del Valle – population: 5,000 – inaugurated its own Casa de la Memoria.)

The clock is ticking. “There are many cases of people around Spain who knew where their relatives’ remains were, but have not been able to find them because they haven’t had any institutional support,” Rebolledo said. “These people have died, they have left this world without knowing and without recovering the remains of their father or mother. We can’t let that keep happening.”

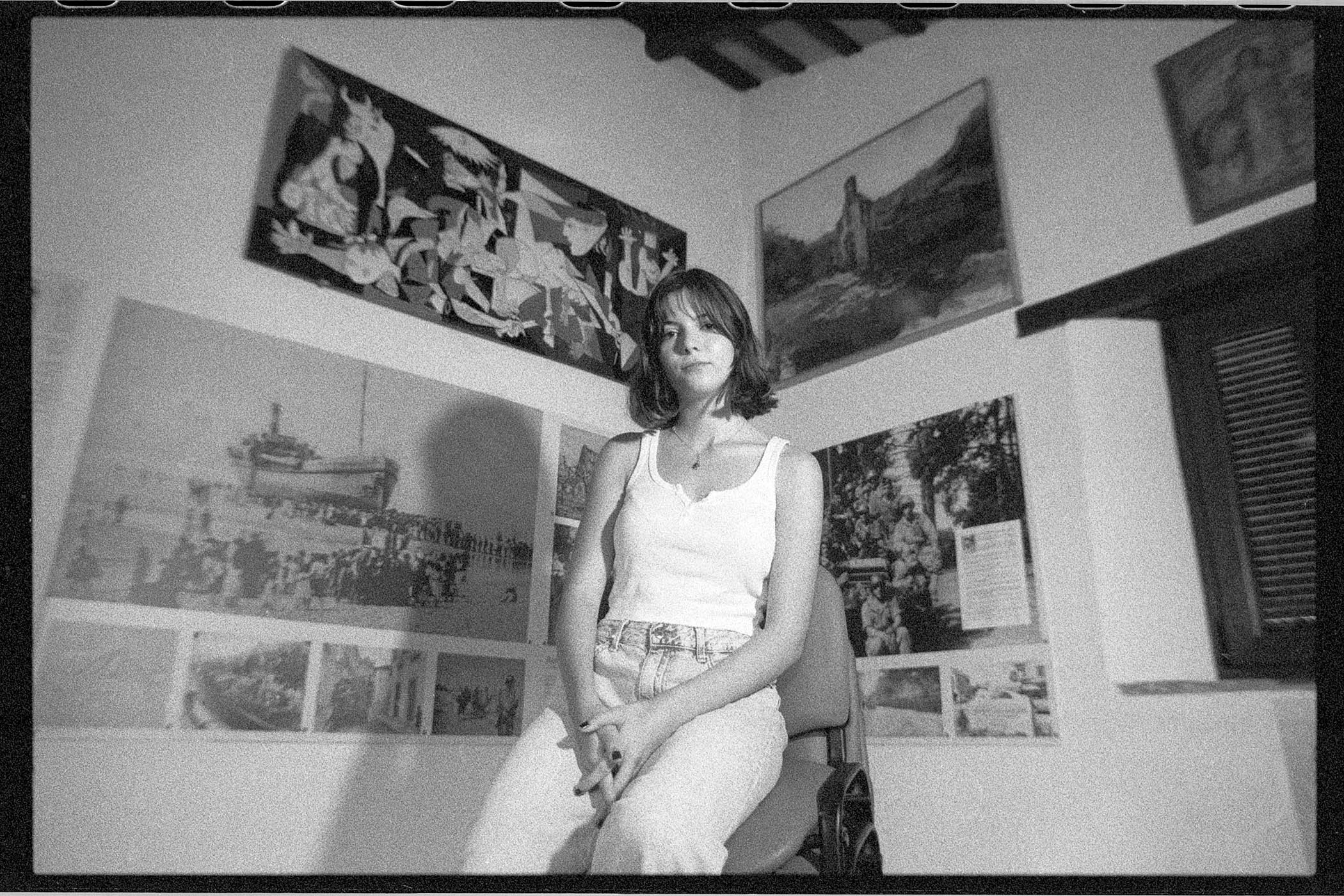

Eva Pizarro Quintana, the daughter of Juan Manuel Pizarro Sánchez, librarian and archivist of the Casa de la Memoria, is part of a new generation committed to preserving the memory of Franco’s victims

Walking down paths of sun-dried mud and shale on our way out of La Sauceda, we passed a group of lads in their early twenties with tattoos and hipster hiking gear. They delivered the usual cheerful walkers’ greetings, then one of them stopped. The young man was named José Antonio and was doing a university project on the mass graves – he had recognised Rebolledo from a local TV documentary.

“I’ve been coming here since I was very young, purely for recreation,” he explained, “but then when you find out everything else about the history, everything that happened here…” he widened his eyes and gestured with both arms, miming a bomb going off. Rebolledo nodded in agreement. José Antonio thanked him reverentially and we proceeded down the shale.

“You asked me earlier: are there reasons for hope?” Rebolledo said, gesturing up the hill. “Well, across the country there are so many students like that, who are writing their final project on historical memory, trying to uncover the truth of what happened in their towns; history students, journalism students, sociology students, anthropology students. There are many sensitive young people who want to learn about all this. That is the reason for hope.”