Frauke Gerbig, 66, clearly remembers the first time she asked her grandfather what he did during the second world war. She was 16 years old and had just watched a documentary about the Holocaust. In response, he ran out of the room, crying. The only information Gerbig could gain from her family was that he had served in the Wehrmacht – the Nazi-era German army – and had been a prisoner of war in the Soviet Union. “The narrative was always that he was a victim,” she said.

Over the years, there were hints that his relationship with the regime’s ideology may have been more complex. “When I was 21 I went to volunteer on a kibbutz in Israel and he refused to speak to me, because he hated Jews,” Gerbig said.

The sense of guilt that her family could be linked to atrocities gnawed away at her. But even after her grandfather’s death, she was the only one in her family who had any interest in seeking out more information. “They just don’t want to know,” she said.

One day early this month, she stood in a classroom at Munich city library for a seminar she hoped could finally bring some answers. She and 13 others, many clutching folders full of family papers and photographs, were attending a workshop by the historian Johannes Spohr on how to use the country’s public archives. As they took turns to share their motivations for researching their family histories, Gerbig felt a little less isolated. “It was so comforting to hear other people have struggled with these discussions in their families, too,” she said.

Germany is famous for its Erinnerungskultur, or memory culture, in which the horrors of the Holocaust and the Nazi regime are commemorated in monuments, museums and national days of remembrance. However, reflecting on what one’s own family may have done during this period has long been more taboo. “It’s only ever been a small minority of people who do this,” Spohr said. In a 2020 survey by national newspaper Die Zeit, 30% of Germans claimed their families had been opposed to the Nazis, and only one fifth said they had been followers – a statistical impossibility.

But Spohr believes things are slowly changing, and more people are coming to him with inquiries. He puts this down to the political climate – the far-right AfD is leading the polls, prompting much soul-searching – and the fact that most of those who lived through the Nazi period have now died. “A lot of people from that generation were not just silent about what they did, but they also silenced other people,” he said.

Spohr came to this work through his own experiences. Growing up in the 1990s, when far-right violence was on the rise in Germany, he began looking into his own family history. He discovered that his grandfather had joined the Nazi party in 1933, and even applied to join the SS. Today, he tries to “empower” people to use the country’s extensive public archives to research their own families. “When you make history a bit more concrete you can gain a better understanding of your own reality,” he said.

A group of Wehrmacht soldiers socialising during the second world war

After the end of the second world war, the allied forces seized extensive government and military files in order to investigate crimes against humanity. These included Nazi party membership details, military records and files relating to the SS. Although only a small number of high-ranking Nazis were convicted, these files are now stored in the Federal Archives, which are housed in 23 venues across Germany.

Related articles:

A s Spohr explained to the Munich classroom, a nyone can put in a request to these archives for documents relating to individuals. Inquirers must provide the name and birth date of the person and an indication of the section they want to search in, such as the SS files or military files.

Using a projector, Spohr shared examples of what attendees might expect to receive back, such as a Nazi party membership card and a soldier identification document. Seeing the date someone joined the party can give clues about what may have motivated them to do so. Military records, on the other hand, are more complicated.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Spohr showed where on the document to look to find out which battalion someone was in. This can be used to request further files on any battles or possible war crimes in which the relative may have been involved. The process can be confusing; he recommended creating a “working document” to keep track of findings.

The attendees, most of them retirees, sat in the ornate room with its high walls and curved ceilings and attentively took notes. Spohr said the average age was higher than usual – when workshops are held on weekends, many younger people attend. The atmosphere was emotional, and some participants were visibly close to tears as they recalled painful memories.

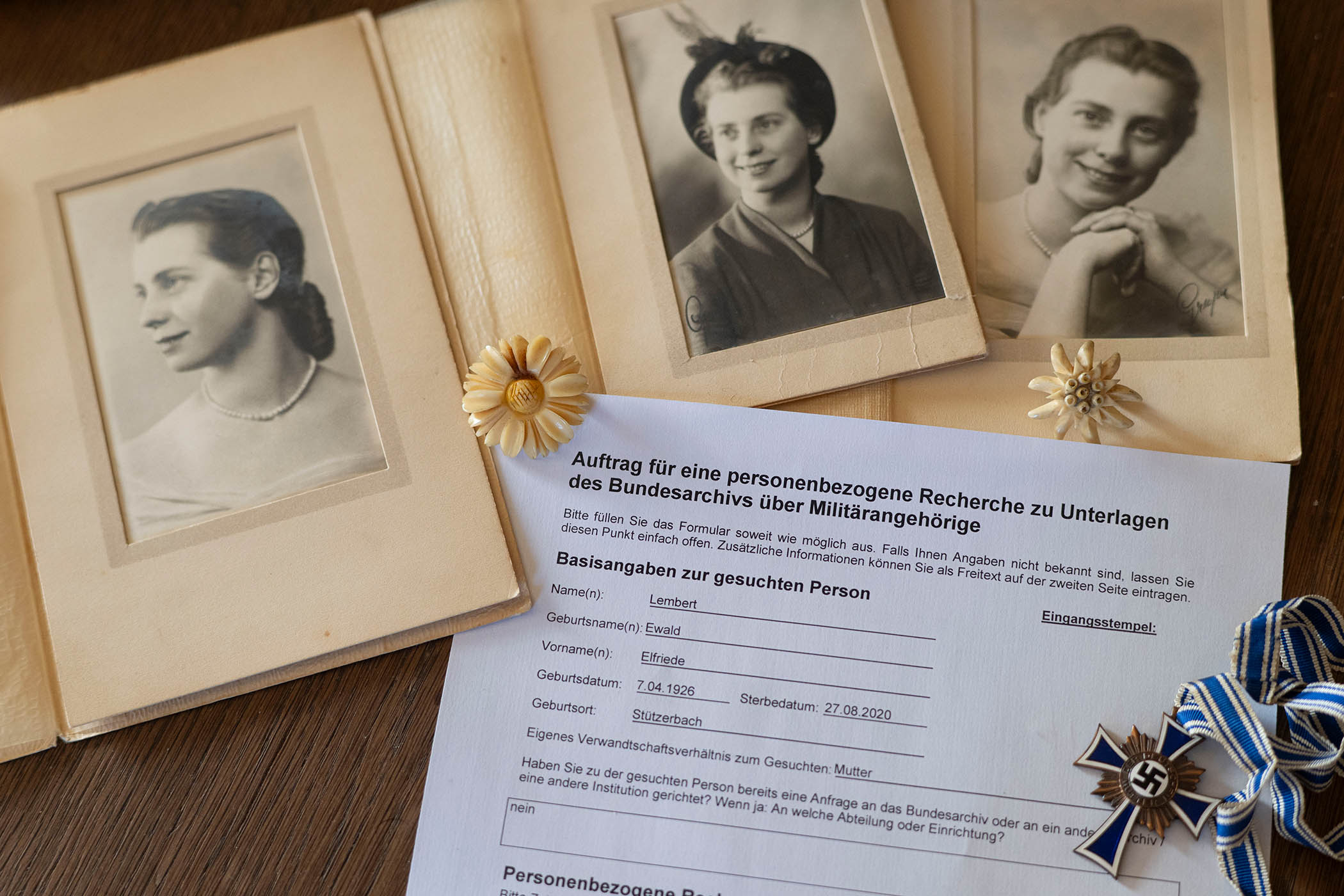

Some people in the workshop have been engaged in their own research already. Through basic googling, Christiane Lembert believes her great-uncle ran a factory that used forced labourers from the Soviet Union. Now she wants to find out more about this, and about her mother, who was active in the Luftwaffe. “I’m still asking myself, ‘Why didn’t I ask them more questions while they were alive?’” the 67-year-old said. She believes she has a responsibility to “come to terms” with her family’s history.

Others want to better understand the generational trauma they have witnessed. “My father said my grandfather, who was a Wehrmacht soldier, was a broken man after the war,” said Angelika Grimm. This affected her father, who was six years old when the war started. “He was very unstable and had severe depressive episodes,” she explained.

Christiane Lembert

As a recently retired psychotherapist, she “wants to better understand the impact all this has on us, on individuals and on society”.

Spohr warns that although the archives can offer facts and dates, many people are left with questions that may never be answered. “People are often most interested in finding out what their relatives thought and felt about what they did, and this is the most difficult thing to find out,” he said. “You can reconstruct the jobs people did and which unit they were in. But you don’t usually have any sources that can make the inner part of a person any clearer.”

He is also sceptical as to whether this type of personal research can halt the rise of the far right. “Maybe that’s overstating the power of memory culture,” he said. “However, it can give us clues as to how these ideologies take over societies, and we can use that to try to prevent it happening again.”

Although she understands its limitations, Gerbig hopes the research will eventually give her a better understanding of her family’s past. “It makes me sad that my grandparents could have supported these things, but if I can say, ‘he joined the Nazi party on this date’ or ‘he fought in this battle’, it will give me more clarity,” she said. “I feel I have a responsibility to my daughters, too, to find this out. I think it’s essential for the health of a family – and the health of society.”

Photographs by Florian Jaenicke for The Observer, Imagno, Getty