Six years ago, in despair, I made a list of the ways I wanted to spend my time, and the ways I actually did spend my time. Then I set the two lists against each other, the better to shame myself.

I was living in a tiny bedroom in an acquaintance’s flat in north London, where I had moved after desperately asking on social media if anyone had a space I could stay for less than usual rent, because I would try to be there as rarely as possible. I was 29 years old and making comically little money. I could not puzzle out a way to exist in the world satisfactorily. I had no degree, no real career to speak of, and I considered myself a failure in all measurable ways.

The ways that I wanted to spend my time were simple: writing, reading, listening to music, watching films – and, most crucially, speaking and listening to my friends and family, then meeting new people I would like to do the same with. The ways that I did spend my time included all those things, but they were overshadowed and contaminated by what I spent much more time doing: looking at my Twitter feed, posting on Instagram, taking pictures of myself to appear not to be a failure.

It was clear to me that I knew what I wanted to be doing with my time – and therefore my life – and it was also clear that these aspirations had little bearing on what I actually did. It was as if I was being pulled away from the way I wished to live. I felt stalked by something outside myself, as well as within.

Alyssa Loh, D Graham Burnett and Peter Schmidt of the Friends of Attention collective

The effort to reconcile my actions and my desires came to mind as I read Attensity! A Manifesto of the Attention Liberation Movement, and when I met the book’s authors, who call themselves the Friends of Attention. It is now, they say, all but impossible “to want what you want to want”. This coalition of “creative collaborators, colleagues and actual friends who share an interest in attention activism” took shape after the 2018 São Paulo biennial, which hosted a programme on “practices of attention”.

“This is what happens,” says D Graham Burnett, a historian of science. “You have a passing interest in a new brand of coffee, and suddenly all your social media is showing you this kind of coffee, and don’t you need to get this one too, and aren’t your teeth yellowing, by the way?” He and Alyssa Loh, a film-maker, writer and fellow Friends of Attention member, are speaking to me at their home, a penthouse in uptown Manhattan. Burnett and Loh’s five-week-old baby is being looked after in an adjacent room. Peter Schmidt, a former student of Burnett’s who now runs the Strother School of Radical Attention, joins us. The three are evidently close, speaking in a fluent triangulation, where one occasionally breaks off to ask the others if what they are saying sounds crazy.

The coffee example is the most basic sort of scenario the Friends of Attention speak on. It’s the one most familiar to us as laypeople who are terrified of what our phones are doing to us: advertising, employed in more insidious ways than before. But the Friends of Attention believe the problem runs deeper: our collective perspective has been corrupted, so totally that we don’t just accept but welcome it. We pay for it, financially and otherwise.

“This is not: ‘Don’t worry, capitalism is going to give you five different kinds of toothpaste, you can make a choice about what you want,’” says Burnett. “This is the opposite. Less free, less choice.”

Related articles:

Participants at an ‘attention lab’ led by the Strother School of Radical Attention

Most of us are by now familiar with the broad mechanisms of the “attention economy” – the hijacking and monetising of consumer attention through addictive channels. The ravages of this system are ever more apparent. Students arrive at college unable to parse simple texts or finish books, and we adults who grew up before universal internet access are not doing much better. When I began to spend time with my boyfriend’s children, I was astonished by how alien their preferred entertainment appears to me: free of narrative and involving a cacophonous overload of inane chatter, noise and visual bombardment designed to achieve total sensory saturation.

We know who is responsible for and who benefits from this encroachment into our internal landscape – tech overlords – but the problem is that we love it. Also, we hate it. But we love it. Don’t we? It feels good. It makes us laugh. It connects us with people we love and like and admire. It shows us interesting information about things we otherwise would never have known. There is a dog who is best friends with a bear cub and also we now know so much about that one particular massacre that happened in the Vietnam war. And what about the Dyatlov Pass incident in the Urals? We are not Alex the droog in A Clockwork Orange, our eyes forcibly propped open to absorb the horror. We gaily open them ourselves.

This queasy complicity in our own degradation has led to a swelling of self-recrimination. People post their hideous screentime averages and vow to leave social media platforms, lock smartphones in safes, or eschew them altogether for old Nokias. I once installed on my phone an alarm clock app that made a catastrophic, upsetting noise when it woke me up in the morning until I finished solving multiple complex maths problems, and made the same noise if my screentime exceeded three hours. And then I wondered why my nervous system was so profoundly shaken.

Attensity! begins compellingly: “We feel it, too.” The book is written collectively, in the first person plural: Burnett, Loh and Schmidt are credited as editors. One of its immediate attractions is that it relieves the hand-wringing instinct to reproach ourselves for our constant distraction. “In a real sense, our attention does not belong to us,” they write. And: “The harms of this new economy cannot be overstated. Human attention is the stuff out of which we care for ourselves, our communities, and our planet.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Rather than bemoan our lack of willpower in limiting our immersion in digital spaces, they mount a more holistic and radical opposition to the forces that hold us hostage there. There’s something a little too appealing about this for me, a person prone to let myself off any hook I conceivably can. It brings to mind the questionable value of the aphorism “there is no ethical consumption under capitalism”, a claim so generic and overused that you could use it to defend arms dealing or tobacco lobbying. However, the Friends of Attention make a convincing argument. Crucially, the collective points not only to the forcible co-opting of our attention but, more fundamentally, to the very definition of attention. The term “attention”, the editors write, has come to refer narrowly to the time we spend on screens. It benefits the tech oligarchy for us to consider it this way.

“The problem with people thinking that what’s at stake is just their attention span,” Loh says, “is that it makes the stakes seem so much lower.” We minimise the problem if we conceive of our attention in terms of the time it takes us to send an email, she adds. “But what if what’s at stake is your personhood and your ability to care? The way that attention underwrites everything that you enjoy – from baking and cooking and reading a book and hanging out with your friend to caring for your kid? That’s not abstract, even if it’s not numerical.”

Loh’s work on attention is informed by her experience in business school, where she was taught that the first step to monetising something is making it numerically quantifiable. She is a persuasive, charming talker. All three are passionate about their work – Burnett has a wiry charisma that calls to mind a benevolent cult leader – but it is Loh who convinces me on the essential aim of their project: to reframe escaping our phones as not punitive, but an opportunity to let in something wonderful. “We don’t have to think about our attention that way,” she says. “And it’s actually essential that we don’t think about our attention that way.”

A hesitant cry sounds. Loh and Burnett’s baby needs to be fed.

Later that evening, I attend an “attention lab” led by the Strother School of Radical Attention. The school hosts, among other events, seminars, which are paid, and labs, free-of-charge workshops where participants engage in exercises and discussions exploring attention. We are in Dumbo, right on the water in Brooklyn, in a room with the soft lighting of an especially nice yoga studio.

What’s at stake is your personhood and ability to care. Attention underwrites everything

What’s at stake is your personhood and ability to care. Attention underwrites everything

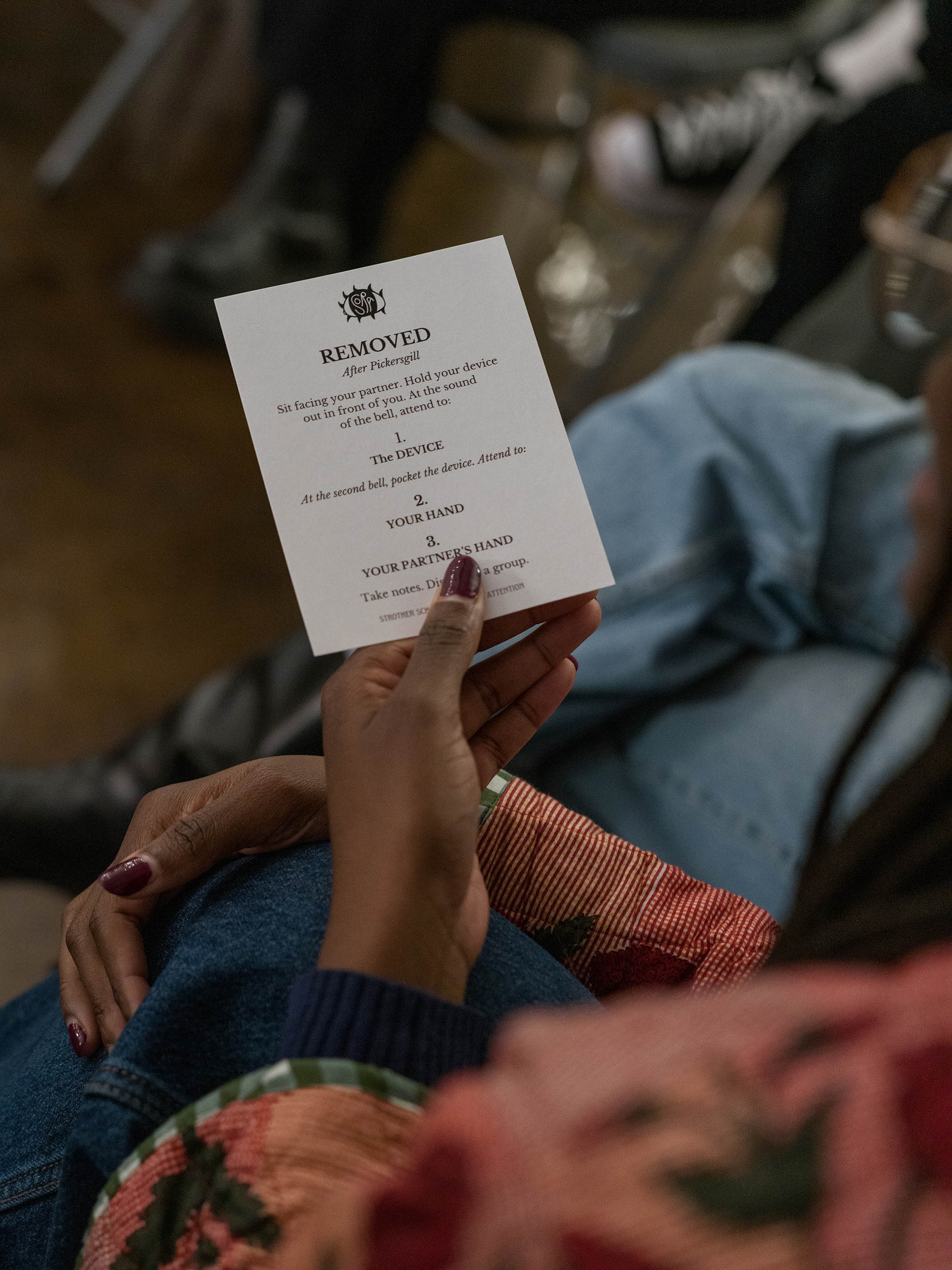

There are cookies and fruit and hot cider, and two dozen people fill the room, sitting in a circle. Our first exercise is inspired by the photographer Eric Pickersgill, whose series Removed shows people posed as if they were staring at their phone, but with the device itself missing from the image, creating a dissonance that drives home how absurd it is to be staring at one all day. We spend a few minutes staring at our phones – just the blank object, not turned on. Then the workshop leader rings a bell and we must change to stare at our own hand. Finally, we turn to the person next to us and stare at their hand.

What can I say? I am not a joiner. Group activities make me bristle. I try to pay attention to what I am thinking and feeling, and find that I am mostly thinking: “I do not want to be looking at my hand.” My partner’s hand is a more enticing prospect, but even that fresh terrain soon loses its appeal. I am beginning to low-level panic when we are asked to share our experience of the exercise.

Fortunately, the second effort of the evening is more comfortable. We are invited to go outside, individually, and sit on the street for 10 minutes and record in a notebook what we observe. This, I like. I am reminded that what I enjoy about being a writer is that I have the “excuse” – as if one was required – to witness things. Perhaps the labs may serve a similar function: to give attendees an excuse to be off their phones – and then to help them realise that they don’t need one. Back inside, we stand in a circle and take turns to read our notes to one another, enjoying the recurrences of our separate but mutual witnessing. Someone reads out their observation: “People looking at their phones,” with a knowing smile and looks around at us, we enlightened few. “Oh, brother,” I think, unkindly.

At the end of each lab, an empty vessel is placed in the centre of the circle. This practice cites a central literary reference made in Attensity!: “In his 1902 novel, The Wings of the Dove, Henry James depicts a crucial, if fleeting, encounter between a fatally ill patient (female, sensitive, anguished) and an esteemed medical doctor (grand, humane, busy). It is a charged rendezvous, and a rushed one. For various reasons, they will have only a few moments together – the time must be stolen from the exigencies of ordinary life and obligation. They sit. And here is how James evokes the redemptive power of that moment: ‘So crystal clean, the great empty cup of attention that he set between them on the table.’”

Workshop instructions

To collectively fill our cup, here at the lab, we must offer a mode of paying attention we value in our lives. “Writing about my dad,” I say. I ask a woman next to me how she had enjoyed the class as we wind down. She pauses. “I’m surprised so many people are here by themselves,” she replies neutrally. When pressed, she says that she wishes they addressed how to prioritise those things you care about but that get lost in everyday life. She had once wanted to be an actor. I think I know what she means. Throughout the evening, I had found myself wishing I was doing the specific things I want to pay attention to in my own life, instead of talking about doing them. And yet the aim of the school is perhaps exactly this: to encourage us to have an awareness of how we want to spend our time.

Speaking to my boyfriend about it the next day, I start to tell him that I didn’t get that much from the workshop, but that I was reminded that I like sitting in a circle discussing things with people. Then, I said, I was curious about why there is no free, self-organising group therapy that isn’t predicated on addiction or specific trauma. Why couldn’t we have the equivalent of AA, but for being alive? I start to get excited as I think about how you could structure it. My interest is aroused, attention rewarded.

A deeply embarrassing truth about my writing life is that it was partly inspired by a line in the Johnny Cash biopic Walk the Line, starring Joaquin Phoenix – a film and musician I have practically no interest in whatsoever. There’s a scene where a record label boss is encouraging a lacklustre Cash playing standards to sing the song he would sing if he only had one left before he dies. Cash rallies, and sings like he’s been electrified. I kept thinking about this when I wrote my first book – what would I write if I could only write one before I died? From there the urgency came.

For me, questions of attention and mortality are entwined. To choose – wilfully, precisely – how to spend our time and where to direct our attention, is to kill off other possibilities, and killing off possibilities is always a reminder that we, too, will die. I feel this in the paralysed stasis of my worst scrolling – that it is a symptom of my inability to face the intolerable reality that we are dying all the time.

Best to stay there, locked into the constant movement of the screen, which is also no movement. Best to make no choices, which is also having thousands of choices forced upon you from morning to night. I am trying to remember now that this manner of containing the terror of living also drains life of its goodness. Whatever song it is we are singing now is the one we’ll sing before we die.

Attensity! A Manifesto of the Attention Liberation Movement is published by Particular Books (£20). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £17. Delivery charges may apply

Photographs by Maria Spann