Portrait by Khuram Qadeer Mirza

After the publication of my first novel, Good Intentions, I had what I can now see was an existential crisis about being a writer. I had no idea what I wanted to say with my second. Everything I wrote felt as if it had no weight, no function in the world. It took me months and several bad drafts to realise that I was wanting to write about myself and the place I come from: Alum Rock, Birmingham. A place I left at the age of 18 for university and never really went back to. But I had no idea how to do it. Where would I begin? What would I write about?

Maybe the easiest thing to do, I thought, was to write about the decision to leave in the first place. Those who make that choice and those who don’t.

There are only ever two responses when I tell people where I come from. Either they have no idea what I’m talking about or they do and ask: “How did Alum Rock produce a person like you?”

Alum Rock lies a handful of miles east of Birmingham city centre. In the 1960s, my maternal grandparents arrived there, along with other members of their family and village, from Pakistan. Immediately, those who already lived there started to leave and a cycle was created. The more people left, the more people such as my grandparents arrived, until it became the place I grew up in. One that is filled with south Asian Muslims, majority Pakistani.

Alum Rock has also, over the years, developed a reputation. To those who know of it, when I tell them that I am from there, they respond with the same ideas: gangs, violence, drugs, tax evasion, forced marriages. Some of this is true, in the same way that some of this is true of south London, where I live now, or Newcastle or Derby or Nottingham, where I have spent some time. Of Bradford and Sheffield and Manchester, where I have relatives.

When I was younger, I wasn’t aware of Alum Rock’s reputation, because we rarely left the place. My grandparents laid down roots immediately; my grandfather working at a factory, buying a house as soon as he could and staying there with my grandmother until the day he died. My mother and her five siblings all live within minutes of each other, their cousins too – a sprawling network of people that I know and who all know me.

Whenever anyone who has left Alum Rock returned, my mother would talk about them disparagingly. “Why don’t they stay away?” she would say. “Why come back?” To her, those rare few who left were giving up on family.

Related articles:

It was this world that I grew up inside. On one hand, there was the safety and comfort of knowing that on any road or street I walked, there’d be someone who would open their doors to me. On the other, I was constantly watched, inside a panopticon of our own making. The lunch lady at school was friends with my mother; the man who owned the corner shop, friends with my uncle; the man who served me a burger, friends with my father; the barber with my grandmother; the grocer with my auntie.

I felt suffocated, trapped, by the sea of eyes around me. That feeling was the driving factor for many choices I’ve made: to leave for university; to work in a different city.

I have always wanted to leave and I’m not sure my family could ever understand that.

Alum Rock Road in 2008. The area is home to many people of south Asian heritage

But they were leavers too. My father left Pakistan in the 1990s, freshly married to my mother, who had travelled there for the wedding the summer before. He’d never been on a plane before that; he knew very little English. Like many men in Alum Rock, he came here with the intent to work and make money, to raise his family out of poverty, and to one day return to Pakistan with the knowledge that his hard work meant that his mother and sisters were better off for it.

When he landed, my father went straight to work in the one job that he knew: driving. Over the years, he tried to become something else. He tried his hand at owning a garage, a fish and chip shop, a taxi company. Each one of these enterprises failed in its own way. During the pandemic, he went back to Pakistan for several months to attempt to build a bazaar. That failed too.

I spent weekends sitting in his garage with my brother, playing on the old computer in the office, which didn’t have access to the internet. We did the same at the taxi base. When he owned the fish and chip shop, my brother and I would sit at the red tables doing our homework until the early hours of the morning. My mother would wake us the next day, asking us if we had a good time. We’d lie and tell her yes, the smell of chip fat on our skin.

My father would say that he wanted to show his sons what running a business was like. He would tell friends who he had hired that he was going to become something, for his family. He’d expand. Not one garage, but three, five, 10. Not one taxi company but a dozen. Not one fish and chip shop but an empire.

When those businesses were sold, at a loss, he went back to taxi driving and we were never allowed to talk about them again. If anyone ever mentioned them around him, my father would explode, anger spitting from his mouth.

Watching my father try to build these businesses as a child and teenager had the opposite effect to the one he intended: I knew I would never try to do what he was doing. I already knew that money did not motivate me the same way it did him.

This is something my father and I have never been able to reconcile between us.

And so I have left my parents twice.

The first time was when I left for university. My parents had told everyone that I was definitely going to get a degree: “He’s the one with the brains,” they said, touting my record at school. He’ll be something. But when it came to that summer before I left, when I told them I was planning on leaving Birmingham, they couldn’t accept it. My father told me I was being a bad son. My mother kept asking me: “What did we do to you to make you want to leave?” At the time, I was angry at them. Looking back, I can see that it was their fear for me, for their child, leaving the safety of the community they had helped to build that made them react in this way.

The second departure was for a job the year after I graduated. I had always wanted to be a writer but didn’t know how to turn that into a career. But while I was studying, I realised that I could work in publishing. Someone needed to edit those books; why not me? I applied for an internship in London, sneaking off on the train for the interview without telling my family. When I got the call the next week, I was overjoyed and shocked. When I told my father, he said: “If you want to go out there and spend your money on someone else’s mortgage, rather than helping your family, then don’t come back.” If I was to guess, I’d say his anger came from the fear of loss, not that he has ever been able to tell me that himself.

There was safety and comfort but I was constantly watched, inside a panopticon of our own making

There was safety and comfort but I was constantly watched, inside a panopticon of our own making

Over the years since, I have tried to explain my leaving to my parents.

At first, it was because the publishing jobs I was seeing were all in London. When I told my mother this, she said: “Is Birmingham not a city?” Then, as the years passed, I told them that my life was in London now. “What about your life here?” my mother asked me. “What about your family?” It wasn’t enough that I came back every four weeks. Not enough that I called and texted. She has only ever been able to see my absence.

Once, I asked my mother if she would prefer that I quit the career I had worked so hard at for the past several years, move back home, marry a woman she chose for me, work some dead-end job. She laughed and said: “Yes, that’s every mother’s dream.” My father asked me for money, seemingly just to see if I would give it, and I handed it over, in the hope that it would make things easier between us. It never did.

The moment I stopped was when I asked him if he really needed my money. After all, his house was mortgage-free; my brother and sister worked and gave him money; I had to pay for my entire life myself. “This is what family does,” he said. “This is what I do. I send money back to Pakistan every single month. I have never failed, even when things were hard. This is what good sons do.”

“But they need your money,” I said. “Do you need mine?”

“It’s not about needing,” my father said. “It’s about doing what’s right for your family.”

The next time he asked me for money, I told him I wouldn’t give it. He told me I was a bad son, that I didn’t care for my family, that he no longer recognised me. I still said no.

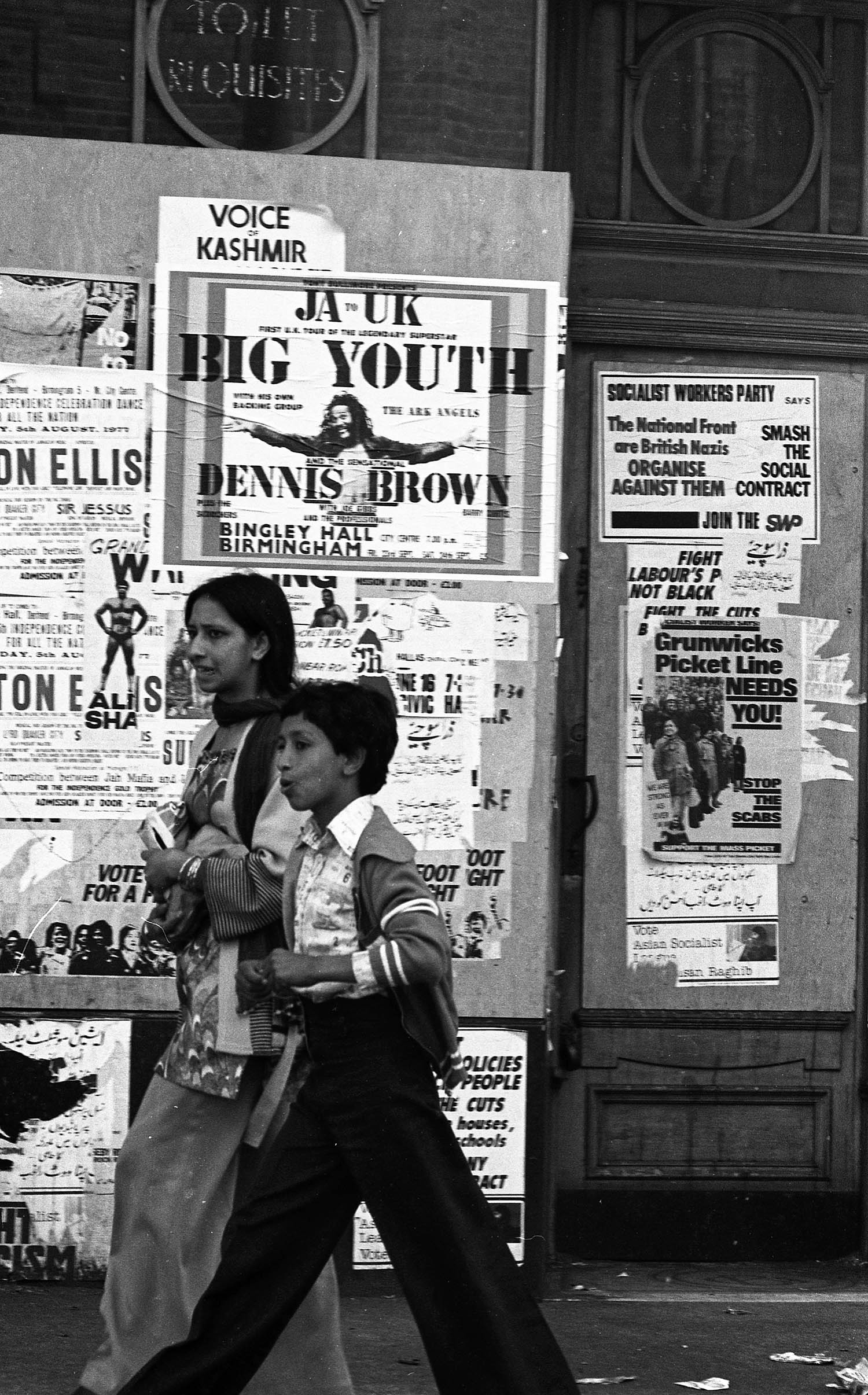

Residents of Alum Rock in 1978

I chose to leave, but the rest of my family chose to stay. Often, I have wondered why. When my brother was in his early teens, he learned something about himself. He was good at maths, understood numbers in a way that no one else in our family did.

This natural strength became the foundation on which he started to lay plans for the rest of his life. He was going to go into engineering, he told everyone. Everyone needed buildings and bridges, and he was going to learn how to make them. Go and work for the big companies, start his own company one day. He was going to make enough money that no one else in the family needed to work. Our father could retire, he’d say. He’d buy us all houses too, pay for our weddings, get our children into private school.

That second year of A-levels, I asked him if he would apply to universities outside of Birmingham. Immediately, my brother said no, and when I asked him why not, he told me that he wasn’t like me. “I don’t want to leave,” he said, so I stopped asking.

The summer after his first year at university in Birmingham, my brother called me and told me he was going to quit. “It’s not for me,” he said. When I asked him why, he wouldn’t answer. Instead, he asked me if I knew about personalised licence plates. He had learned about them through a friend of his and had decided that this would be how he made money.

He had a plan, he told me. He would buy plates that were perennially popular, people’s names, sit on them until someone wanted to buy them and then sell them for more than he paid. Simple, he told me, describing a world in which licence plates could sell for millions of pounds, placed on expensive cars that were often being driven through Dubai by men who looked like my brother and me.

“What about university,” I asked him, “engineering, your own company?”

My brother waved all that away. Did I know, he asked me, how hard it was to get a job in engineering in Birmingham? “It’s one job and a hundred of us applying.”

Over the four years of his degree, my brother would call me and tell me he was going to quit. I’d beg him not to. You’re the smart one, I told him; you have to finish. He did finish his degree. Now he works at the Royal Mail warehouse around the corner from where he lives, still in our parents’ home, sells personalised licence plates online and hasn’t applied for a single engineering job.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

My brother is not the only one in our family who had ambitions.

There is the cousin who wanted to study computing and work at the big tech companies, who asked me for help on his personal statement to get into university, who quit after his first term because he found it too hard, who decided to become a bouncer instead. When I asked him why, he told me the money was easier.

Or the uncle who attempted to own his barber shop, failed and then worked for an energy company on commission. He ran through our family, knocking on doors and calling endlessly, urging everyone to switch.

Or a relative of mine who tried to get me to invest in a cryptocurrency scam he was running, telling me how he could triple my initial investment. “A few grand is nothing for you,” he told me, eyes manic, “big man like you with your job in London.”

Or the one who did a degree in dentistry but now works at Tesco. The one who studied photography but now doesn’t work, married with a child. The one who wanted to be a nurse but now works as a receptionist at a GP surgery. The one who works at the local McDonald’s. The one who doesn’t work at all.

My father saw his migration as necessary; he has only ever seen mine as narcissism

My father saw his migration as necessary; he has only ever seen mine as narcissism

When my father left Pakistan, he did so for his family. It is the mantra he has repeated his entire life.

But when I made the decision to leave for myself, my father’s view was that it was selfish of me to do so. To choose myself over my family. My father saw his migration as necessary; he has only ever seen mine as narcissism.

My parents were also worried that if I left, two things might happen: the world might be unkind to me and I might never come back. The first was inevitable; the second I tried to fight.

But it is true that I don’t go home as often as I would like. That I have missed many things by being away: births and deaths, marriages and divorces, birthdays and graduations. But, nearly 13 years after leaving for that first time, it is hard to return when the one question I am asked, repeatedly, is: when am I coming back?

This question is not just asked by my parents but by my siblings, my aunties and my uncles, my cousins, our neighbours and family friends. Because this question isn’t just about me; it is, of course, about them too. Because the decision to leave Alum Rock isn’t just mine, it’s a collective decision, the consequences of which are felt by those who remain. For most, the burden of that decision is so great, it’s easier to never need to make it, to just stay.

I am not the only one who has left, but those of us who do are few and far between. For the rest that choose to stay, where did their ambitions go? Because if my brother can’t find an engineering job in Birmingham, and leaving is not a choice, then it’s easier to sell licence plates from the comfort of his childhood bedroom. If my cousin finds his university work too hard and the idea of working at a tech giant in London feels impossible, it’s easier to become a bouncer instead. And easier for my father to forget that he ever left his home and call me a disappointment for leaving mine.

Who Will Remain, Kasim Ali’s second novel, is out now (4th Estate, £16.99). Order a copy at observershop.co.uk for £15.29. Delivery charges may apply.

Photographs by Getty Images/Brian Homer/Courtesy of Kasim Ali