I remember the uncommon arrival of Anthony Bourdain in the public consciousness oddly well. Word spread like the really bad kind of chip-pan fire. One day, a certain subset of people were absolutely fine about ordering fish in a restaurant on a Monday; the next, all they could talk about was why this was the move of a total amateur. Newsflash: if the place in question was open on a Monday, then the monkfish had to be avoided like the plague. Obviously, it had been lolling around since Friday morning, awaiting a weekend rush that had never fully materialised. By Tuesday, it would be in the bin, its shiny-eyed, non-whiffy replacement already en route in an ice-filled tray. Only a total idiot would order it on a Monday.

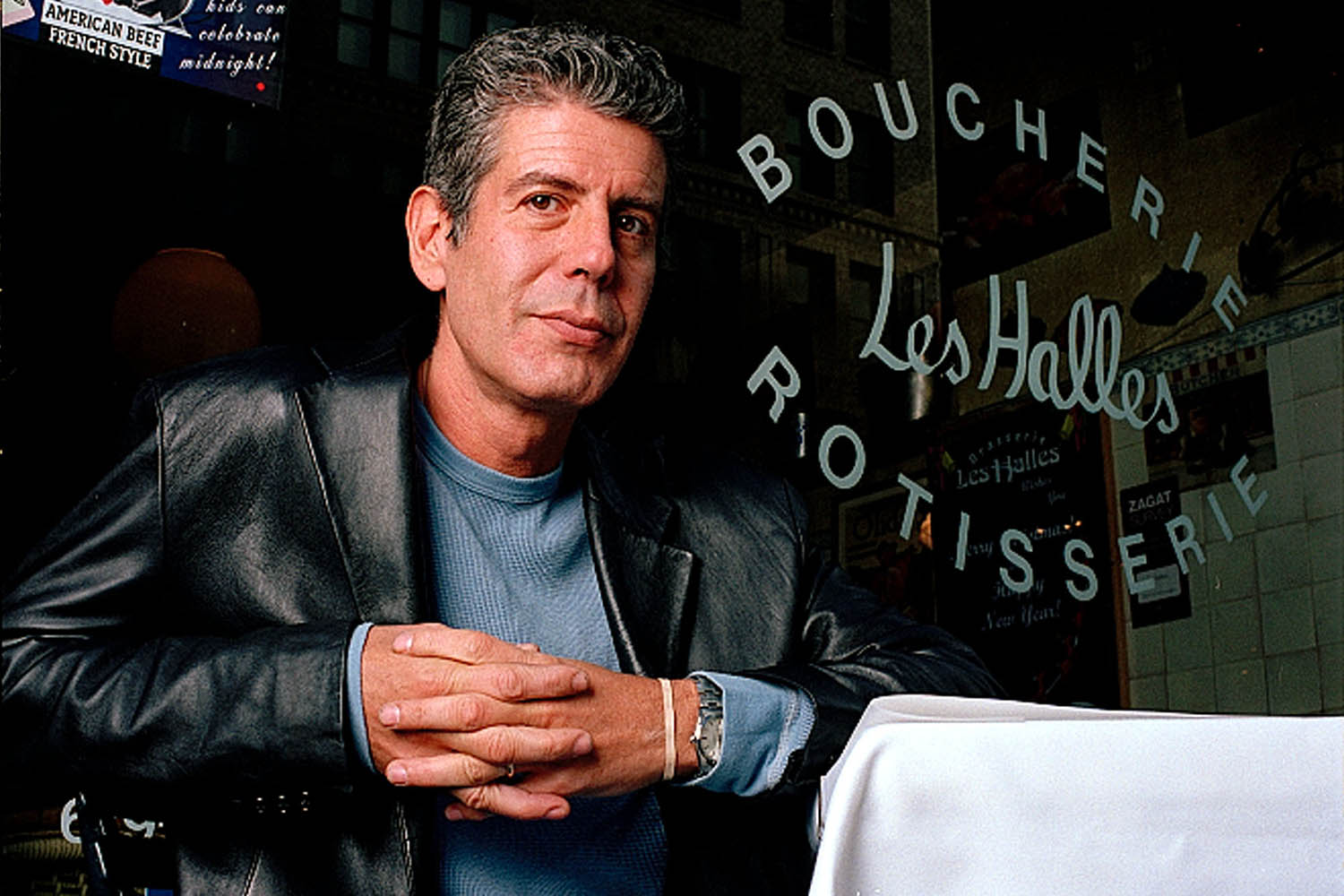

This bit of insider information, and many others like it – another headline: chefs save the toughest, most gristly cuts of meat for diners who insist on ordering steak well done – came courtesy of a piece that appeared in the New Yorker in April 1999, and such a big sensation did it cause that it set Bourdain, then a chef at the Brasserie Les Halles in Manhattan, on the course to international fame and notoriety. A book followed, Kitchen Confidential, and then many TV shows, and even a few novels.

In a way, his rise was paradigmatic of the way authenticity works. From the moment Bourdain set pen to paper – “this life is the only life I know” – his authority was indisputable; even now, I’m more inclined to eat out on Thursday than Friday, Bourdain having informed me that chefs like weekday diners the best (though whether this is true, I’ve no idea). But in the end, the very act of spilling also took him away from his wellspring, from the world he truly loved. Out on the road, he was said to be lonely, no matter how many frog’s legs or chicken’s feet he got to eat for the camera.

What the book does is make you a better customer, more patient

What the book does is make you a better customer, more patient

What’s strange and wonderful, however, is that such a paradox only makes Kitchen Confidential seem all the richer now: more true, as well as painfully poignant (Bourdain killed himself in 2018). The book celebrates its 25th birthday this year. In the UK, there will be a new edition introduced by Irvine Welsh; in the US, a film, inspired by the chapter in which he describes how a summer in Provincetown, Massachusetts, turned him on to cooking is about to begin shooting with the Bafta-nominated Dominic Sessa as Bourdain. I went back to it for the purposes of this column wondering how it would stand up, but blow me if it didn’t knock me down with just the same force as before. Its success, I remembered all over again, is as much a matter of noise (the din of a kitchen at full throttle) and comradeship (the closeness, the common language) as it is of a passion for blanquette de veau or mac ’n’ cheese with no fucking truffle oil. It comes at you like a mallet tenderising meat, all clarity and conviction.

It still reeks of testosterone, of course. Twenty-five years ago, it was nearly always men who wrote about Bourdain, swooning at his elbows. But against this must be set headier smells: shallots, garlic, butter in a pan. And it’s so generous, though admittedly not to vegetarians and “their Hezbollah-like splinter faction, the vegans”. Like a string of perfectly seasoned sausages, he lays it all out for you, the restaurant from open to close, a world in and of itself. It’s not a cookbook. It’s not even a book about food per se; it’s more anthropological than that.

What it does do, though, is make you a better customer: more patient and understanding as well as more usefully cynical and keen eyed. Restaurants have moved on in the years since it was written, shifts having taken place in fashion and attitude that Bourdain would note himself in later editions (his exhortation that diners should always listen seriously to waiters preceded the dreaded concept – as in: “Do you know the concept?”). But some things never change. Brunch is usually a rip off. Chicken is for scaredy cats and the undiscerning. Shellfish is a bad idea in an empty restaurant, whatever the day of the week.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy