Illustrations by Oriana Fenwick

I used to scorn fussy eaters until I became one. For years, food was an integral part of my identity. Eating it, cooking it, writing about it. As a suburban child of the Findus Crispy Pancake generation, moving to London in the mid-noughties felt like Dorothy stepping into a technicolour, flavour-laden Oz. I had spent my teens on a miserable series of Ryvita-based diets; it was liberating to rebrand my newfound greediness as “foodieness”. My appetite knew few bounds. Raw or fermented or tentacled – I’d eat it. I prided myself on being gastro-literate. I judged those who asked for a fork or paled at an unfamiliar ingredient. A broad palate was synonymous with being an interesting person, I thought. A sensual person. I once stopped dating someone perfectly nice because his pickiness at dinner was so deeply unsexy.

But that was then.

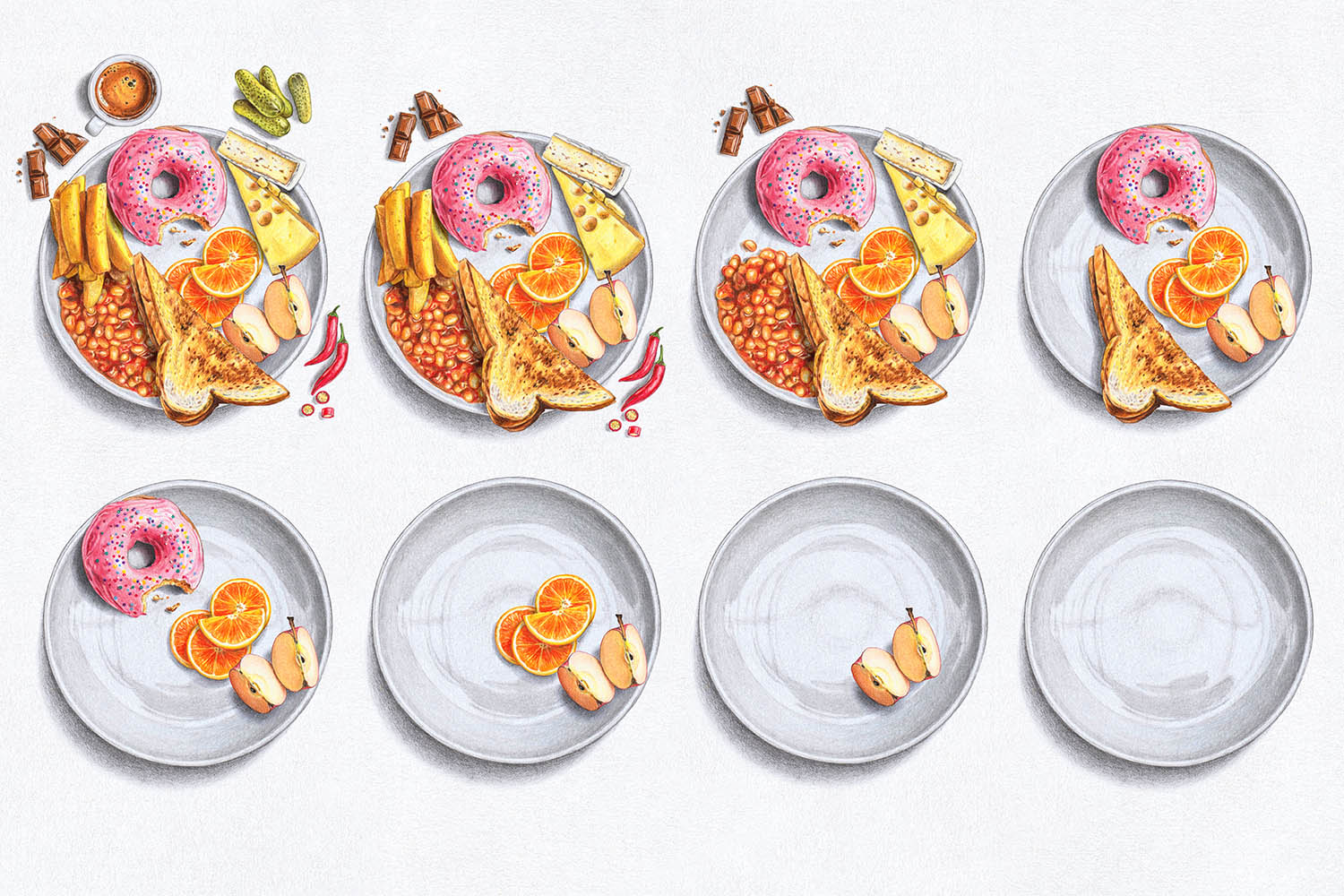

Over the past decade, gradually worsening digestive issues have whittled down my menu options like a cruel parlour game. A combination of acid reflux, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and a propensity for what my mother would call “coming over a bit weebly” have conspired to kick me out of Oz and back to the land of the beige.

First, booze had to go, after my hangovers became so savage that a single beer could render the whole next day a queasy write-off. Then caffeine, which was a boon for my anxiety but not my matcha habit. Next up was chilli, garlic, raw onion, citrus, pickles, tomatoes, pineapple, beans and legumes, deep-fried anything and, most recently, most egregiously, dairy and gluten. Enjoy every pizza, for you never know when it might be your last.

At home, I live now on a rotation of tedious “safe” meals that won’t upset the apple cart (apples are fine). I bastardise favourite recipes to remove all the parts I can’t eat, which, reliably, are the parts that make them delicious. Eating out has become an exercise in torturous Fomo. I have the kinds of conversations with waiters that would once have prompted me to dump myself. It’s virtually impossible to find meals without any verboten ingredients, so instead I subsist on calculated risks, weighing up the option least likely to leave me bilious and burpy all night or racing for the loo all morning. Which sounds like a dull way to live, but there’s still room for surprises. Sometimes my tap water is served with lemon in it.

Still, at least I’m on-trend. IBS and gastroesophageal reflux disease (Gerd) are both on the rise – though it’s hard to know if this is down to changes in our microbiome or increased awareness. Gut health is hot right now. And profitable. Start-ups are racing to sell us artisanal sauerkraut and probiotics in cute, pastel packaging. On social media, being a “hurty tummy girlie” who can’t quit iced coffee is relatable-meme fodder. TikTokers shine light on conditions like Crohn’s, while forums and subreddits spill over with sufferers swapping tips and looking for secret cures.

But offline, it can still be lonely. Both Gerd and IBS are associated with a reduction in quality of life, the latter particularly for women, who are more likely to feel stigmatised by their symptoms and by the pressure to conform to social norms. It’s tough to be the only person at the table not sharing the sharing menu, or using Gaviscon as an after-dinner mint. Too abstemious and you’re treated like a killjoy; too dyspeptic and you’re Henry VIII.

Medically, I know I’m lucky that nothing sinister or life-threatening is going on. I’ve been tested, scanned and prodded, diagnosed with a small hiatus hernia but otherwise declared healthy. Doctors have been supportive to a point, but the NHS is facing many urgent crises, and “Lauren can’t have kimchi any more” is not one of them. I leave every appointment with a refilled prescription for omeprazole and some variation on the same, weary advice: if you can’t stomach it, don’t eat it.

But this logic spares no thought for the social and emotional value of meals. Food is cultural currency, after all. Many of my friendships were forged through food. Late-night kebabs. Queuing for photogenic brunches. Jostling for a sliver of hispi cabbage in the small-plates tyranny of the mid-2010s. And while the opportunities to commune around a table are rare now so many of us have moved out and had kids, they’re all the more cherished for their scarcity. I want to eat, drink, be merry, not spend the night picking curls of spring onion from a dressing-free salad.

'I subsist on calculated risks, weighing up the option least likely to leave me bilious and burpy'

For the people-pleasers among us, a hurty tummy can be a price we’re willing to pay to not seem demanding, uncultured, or uptight. My mother, who is gluten- and dairy-free for medical reasons, carries emergency sandwiches everywhere so that she never has to make a fuss. My friend, Amy, regularly loses hours to IBS attacks because she’s too shy to ask for alternatives in the work canteen. I deliver whole speeches (“I like chilli, it just doesn’t like me!”) to convince patient waiters that not being able to eat spicy food doesn’t mean I voted for Brexit. Then there’s the simple fact of not wanting to deprive ourselves.

In many respects, things have never been easier for the free-from community. We can get gluten-free toast with our fry-ups, vegan cheese, oat-milk everything. There are recipes online for every conceivable intolerance and, as of 2021, a law in place to make sure the 14 most common allergens are clearly labelled on pre-packaged food. Hospitality staff regularly bend over backwards to ensure no contaminants pass my lips, even while I’m yelling “no worries if not!” at their retreating backs.

But at the same time, menus are more complex than they’ve ever been, and diverse eating more celebrated. Everything good these days comes drizzled in hot honey and festooned with pickles. And unless you’re dangerously allergic or have a “proper” condition like coeliac disease, dietary requirements are still a punchline. People roll their eyes at the preciousness, the pretension, the Gwyneth Paltrow of it all. True foodies have gone back to cow’s milk in their coffee, onions in their Martinis. It pains me not to join them. But it pains me if I do.

So, I’m a hurty tummy girlie on a mission. Determined that the rest of my life won’t be measured out in egg sandwiches on bread that tastes like wadding, I’ve done as so many people do and started looking for solutions in the world of alternative medicine. So far, my odyssey has taken me through an array of Instagram-ad supplements, a bucket of papaya enzyme and a brief dalliance with kombucha, all of which bore results more noticeable in my bank balance than my stomach. There are so many variables – in meals, but also in life, such as stress and hormonal changes – that it can be hard to pinpoint what’s making things better or worse. The allergy and intolerance test I paid more than £200 for last year has been widely discredited. But we can’t discredit the very human need for answers, or the hopeful urge to search for cures.

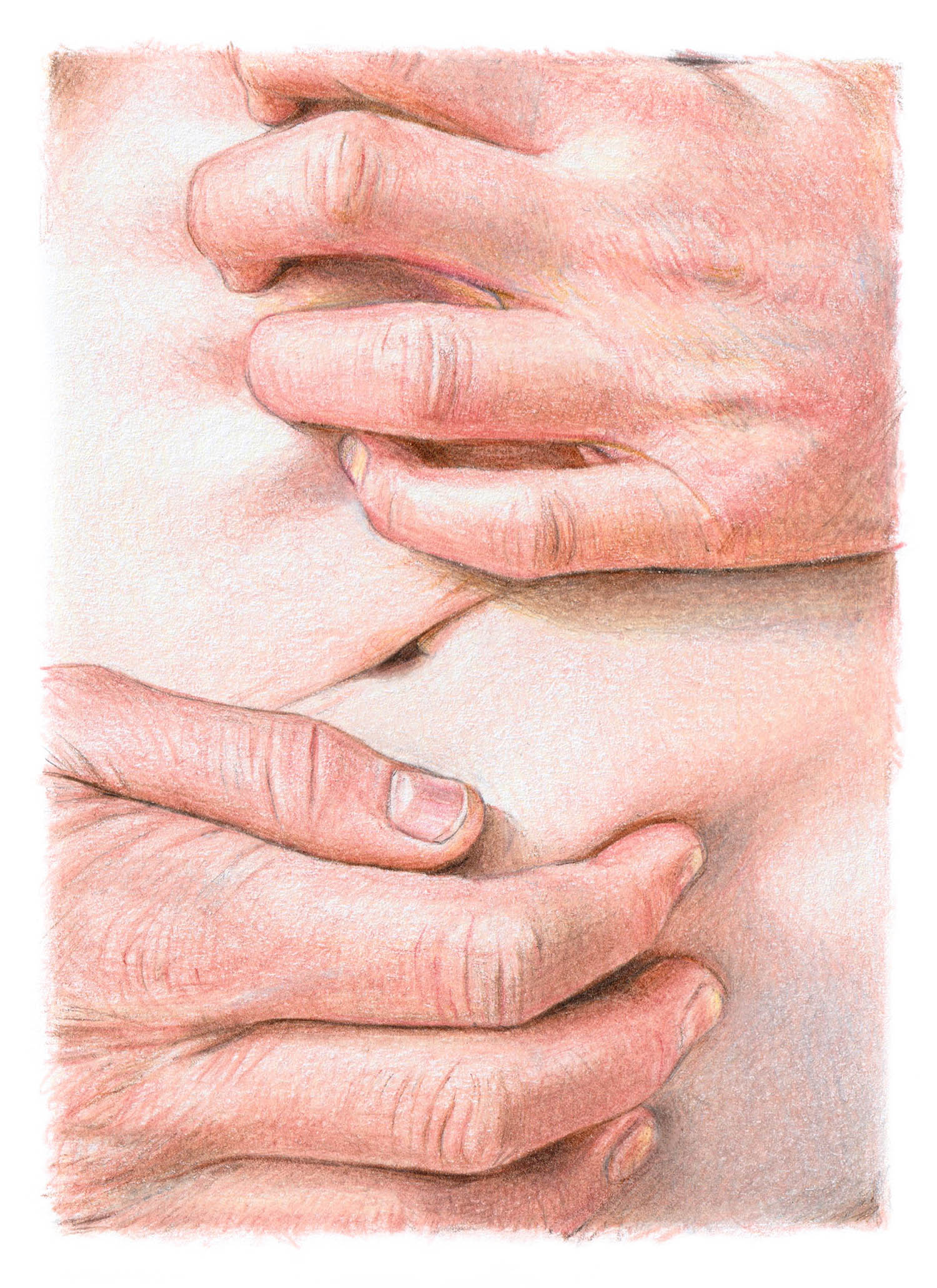

Finally, I arrived at a different kind of treatment, with a top-down approach: a hypnotherapy app. Designed specifically for IBS, it works on the premise that physical symptoms, such as pain, bloating, diarrhoea and constipation are the result of “visceral hypersensitivity”, or a “miscommunication between your gut and brain”. The company, Nerva, claims that listening to hypnotherapy sessions for six weeks can effectively reprogramme this connection, teaching our bodies to ignore the “false signals” that commonly cause flare-ups. Ergo, in six weeks, I could be eating pizza again.

To start, I took a detailed quiz on my gastrointestinal history (no wrong answers!) and tapped a button to vow that I will commit to daily sessions. Then after some educational preamble, I made myself comfortable, closed my eyes and listened as a sultry female voice urged me to breathe deeply and imagine a wave of relaxation passing over my body. Before long, I was walking in the foothills of a lush mountain range, admiring wild flowers and taking in the gentle sounds of nature. All very chic until she used the word “bowels”.

Nerva is one of a growing raft of brands using hypnotherapy to target physical ailments. Its parent company, Mindset Health, also makes apps for chronic back pain and menopause alongside more traditional hypnotherapy goals, like stopping smoking. There is scientific backing: huge advances in understanding the interplay between our bodies and brains, with numerous studies showing that for certain chronic conditions, hypnotherapy can be as effective as modern medicine. A 2015 study of 1,000 IBS sufferers found that 76% experienced symptom relief after 12 gut-directed hypnotherapy sessions, while a clinical trial from 2016 found it worked as well as the Low FODMAP diet (restricting certain carbohydrates) at managing IBS symptoms.

Alex Ford, professor of gastroenterology at the University of Leeds, told me recently, “The gut is supplied by something called the enteric nervous system, which is bidirectional. Messages from the brain come down to the gut to control function and sensation, but messages also get sent back from the gut to the brain. And some of those messages can be misinterpreted as being pain signals, when they’re not.” A lot of treatments, he said, “only act peripherally, on the bowel, but therapies like gut-directed hypnotherapy or IBS-specific cognitive behavioural therapy [CBT] work on the brain-gut axis, to try and improve the communication between the two.”

Nerva’s digital approach is still new, but evidence is promising. “It seems these apps are demonstrating that perhaps you don’t have to have a human therapist involved in the delivery for them to still be efficacious,” Ford said.

I’ve never done the Low FODMAP diet, because it sounded too sad and, without locking myself in the house for six weeks with only tuna and beansprouts for company, I couldn’t see how I’d ever realistically stick to it. But lying down with my eyes shut for 12 minutes a day? That I could do.

During hypnosis, my thoughts wandered down a memory lane of once-loved meals

During hypnosis, my thoughts wandered down a memory lane of once-loved meals

The app assured me that it’s OK for my thoughts to wander during hypnosis, and they did – down a memory lane of once-loved meals. Slurping fiery ramen with my husband behind steamed-up Soho windows. Ethiopian stews spooned on to sour injera bread. Gout-inducing Christmas cheeseboards. Burnished slabs of lasagne. Colin the Caterpillar…

Nerva is only designed to treat IBS, not acid reflux, so I knew it wouldn’t be a complete cure for me. But even so, it was hard not to feel impatient when, a couple of weeks into the programme, my stomach was still behaving like a classic diva. I threw caution to the wind and ate a few forkfuls of my toddler’s bean and lentil chilli. Wind threw my caution back again.

And I felt guilty that, for all my enthusiasm, I was not doing the programme perfectly. I skipped a few sessions when life became hectic, and fell asleep during a few more. I got frustrated with the lack of immediate results, convinced that if I could only stop thinking about work and parenting and life admin, if I could apply myself to the app with pure, nerdy devotion, I might have got better faster. It’s hard not to buy into the idea that bodily peace is only ever an app or a purchase away. If the greatest lie wellness culture ever sold us is that we can “fix” ourselves overnight, the second is that it’s our own fault when we can’t.

Not for the first time, I found myself fantasising about a kind of intensive medical bootcamp-cum-spa-break – like one of those Swiss resorts for millionaires, but with endoscopies and Cat scans – where a team of expert doctors with nothing else to do would go about solving the mystery of my body. Where I could spend a month with no social commitments or caring responsibilities; no soft-play toasties or dinners grabbed in railway stations. Just time and space to chew my way through a stringent ladder of chef-made meals and back towards optimal health. But in reality, I can’t live under test conditions. Compromises have to be made, meals have to be eaten on the hop. But while my flare-ups didn’t change much at first, as the weeks went by, there were more subtle shifts. A cheeky dollop of hummus here, a bao bun there, slipping in without drama.

Around week four, the point at which Nerva says most people start to see improvement, friends came to visit and we ended up at a pub with a menu where every single item has a chilli icon next to it. At first, I panicked and ordered chips with no seasoning. But when the food arrived, it looked so good that I decided to experiment by eating half of my husband’s meal (he’s an ally). I needed to pop a couple of Gaviscon on the way home, but the sky didn’t cave in. Nor did my lower intestine.

And the next day, I was fine. Fine enough to split an elaborate tasting platter at a favourite local restaurant, without quizzing the waiter or requesting all sauces on the side. I started to notice that when I’m at my happiest and most relaxed, my stomach is too. Perhaps this shouldn’t be such a revelation. On holiday, I can go ham on aioli without repercussions. On our wedding day, I drank half a jug of custard. But I was so focused on solving the mystery of my stomach that I didn’t stop to notice the role my mental state might play.

I can’t lie for the sake of a happy ending: progress has not been linear. There was the quiche that threatened to ruin a weekend, the half-a-glass of champagne that had me confined to a train toilet for an hour. But I can say that things are better than they were. Perhaps I’ll never again be able to eat with the gusto of my early 20s (can’t fight ageing, after all), but I’m hopeful that in time, I could coach my gut to be less of a drama queen. And in the meantime, I can shake off the shame and anxiety that exacerbate those symptoms and destroy my sense of self.

On my deathbed, will I look back and regret the meals I didn’t have, more than the heartburn I did? Hard to say. But I know I’ll never stop loving food. Even if it doesn’t always love me back.

Lauren Bravo is the author of Probably Nothing (Simon & Schuster, £9.99). Order a copy at observershop.co.uk for £8.99. Delivery charges may apply

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy