Photographs by Antoine Georgelin

I must admit I travelled to Basel with modest expectations. It is an enviable realm of expensive hotels and on-trend boutiques, the five-star home of Roger Federer, dripping with images of banks, elite watches, chocolates and snow-capped peaks. But it is not one of your epic cities: it feels placid, barely touched by grand events. It doesn’t take long, however, for these prejudices to be brushed aside. Initially this is a matter of sheer geography, since Basel is close to being the exact centre of Europe. If we imagine a giant X with London and Athens on one axis and Madrid and Warsaw on the other, this is the point where the lines cross. It stands on the hinge between Switzerland, France and Germany. Visitors arriving by air have a choice of three national exits, and passengers entering by train find that some platforms are German-bound and some aim only at France.

There is an even more powerful geographical feature: the Rhine. This is where Europe’s mightiest river, swollen by meltwater from the shrinking Alpine glaciers, turns north towards Germany’s industrial heartland. Tourists can only gasp at its tremendous scale. Already a monster, it is at this point as wide as the Thames at London Bridge, yet it still has 400 miles to go before reaching Rotterdam and the North Sea.

The sense of this being a profound fault line is reinforced by the fact it was the site of Europe’s heaviest earthquake: back in 1356 a monstrous two-day judder set fire to the entire city of Basel and toppled every major building within a 20-mile radius.

Bridge of sighs: a view across the city with its riverside setting, spectacular architecture and surrounding hills

This topography makes Basel unusually easy on the eye, since it enjoys a spectacular riverside setting. But it has also equipped it with a storied past. In early times the Rhine was a barrier between Rome’s French empire and the forests of Germania: the remains of Augusta Raurica lie a short boat ride upstream. Then, in the Middle Ages, it became a bridge between those worlds and a hive of printing and papermaking – it was in Basel’s university that the scholar Erasmus (originally of Rotterdam) produced his translation of the Bible. It thus trembles with echoes of early humanist Europe: medieval houses and old mills, Renaissance turrets and façades coat the hill facing the cathedral.

Only later, in the 19th century, did the river become a highway. A German engineer named Johann Gottfried Tulla masterminded the “taming of the wild Rhine” between here and Cologne, sculpting the unruly stream into a navigable road by strengthening its banks and reducing its length by 50 miles. At a stroke, Basel became an inland port, and rustic Switzerland, then a backwater, was transformed into a trading superpower in pharmaceuticals and luxury goods.

This combination of ancient heritage and modern affluence has made Basel a grand city of art. It has some 40 high-quality museums, all worth exploring. The celebrated Kunstmuseum (opened in 1661, but it now has a super-modern extension) is Europe’s oldest national institute, while the playful Tinguely Museum, dedicated to the celebrated Swiss sculptor Jean Tinguely, brings an avant-garde flourish. The 60m-long mural on death in the History Museum might not be one of Europe’s most cheerful works, but it is certainly unusual.

Old Masters: The Kunstmuseum, founded in 1661, is Europe’s oldest national institute

This artistic strand of Basel’s personality was given an unlikely boost in 1967, when a Swiss plane crashed in Cyprus (killing 126 people: one of the worst disasters in early aviation). In the grief-stricken aftermath, the airline’s owner was obliged to sell the family’s pair of Picassos, at that time on loan to the Kunstmuseum. But a local uprising immediately demanded that the paintings be “saved” for the nation.

That meant buying them for millions of Swiss Francs. The city pledged two thirds and launched a campaign to raise the rest. Children cleaned shoes; students held vigils; residents waved Picasso banners and sold Beatles-inspired “All you Need is Pablo” badges in the street. Everyone chipped in and somehow the money was raised. Some Basel citizens, however, were angry that so huge a sum was being spent on art rather than on social causes, and that led to a referendum – a well-grooved Swiss way of settling disputes. It took place in the run-up to Christmas, and art won. The paintings stayed where they were.

When the artist heard what had happened he invited Basel’s mayor to visit his hilltop atelier in Mougins on the French Riviera. There, to express his gratitude to Basel’s citizens, he donated four more of his works to the city. A Swiss collector donated a Picasso of his own. And so the Kunstmuseum found itself with the nucleus of a serious Picasso collection. It already had the world’s largest set of Holbeins; now it had entered the 20th century.

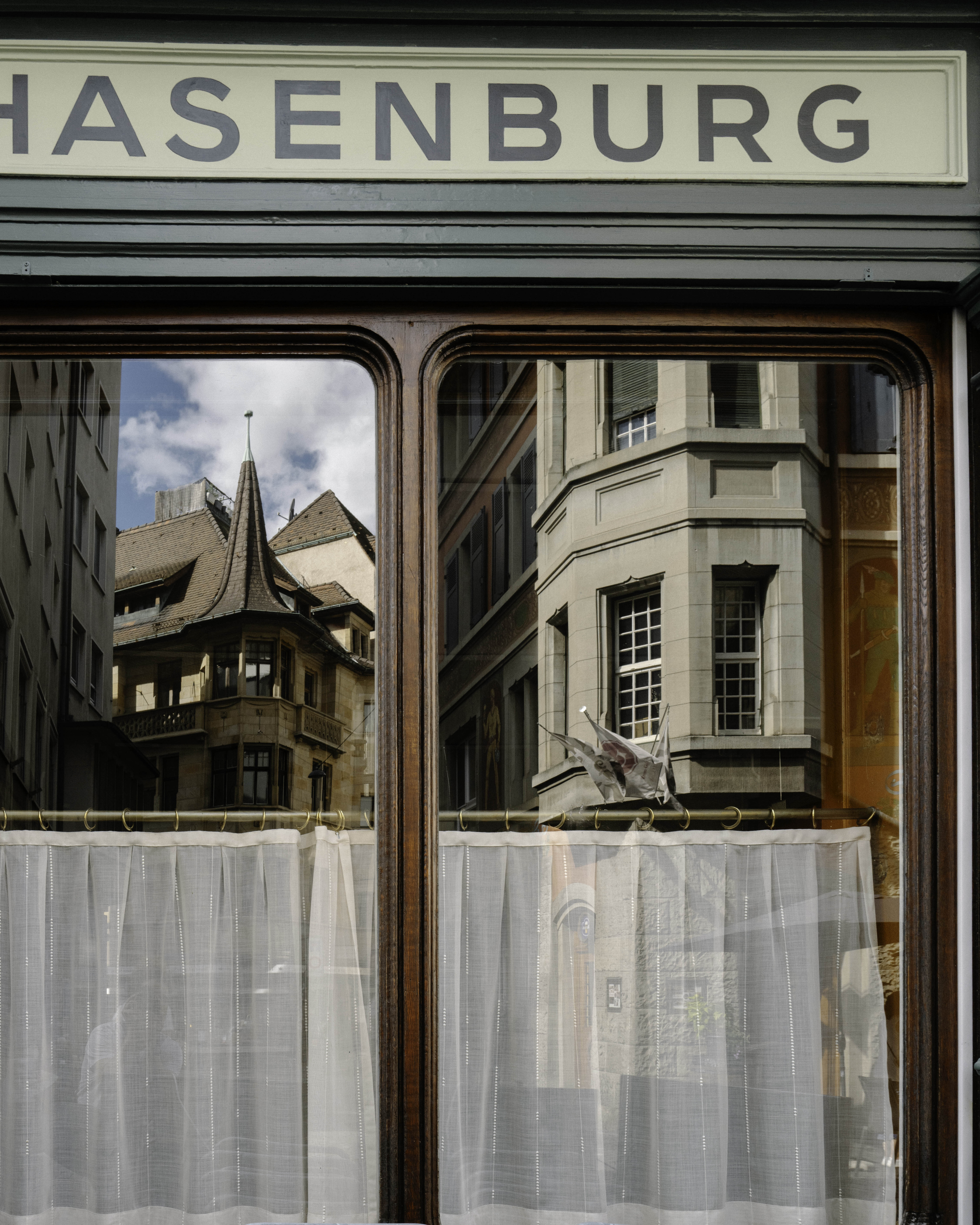

On reflection: try the Hasenburgh, a fine city centre restaurant and pub

The city went on to become a magnet for art lovers and home to Europe’s leading international art fair. A square near the railway station was named the Picassoplatz in honour of the escapade and, in 2018, the museum saluted the 50th anniversary of the public presentation of the paintings with a festival of exhibitions and events.

This is why modern tourists are treated not just to a view over the three countries on whose border it stands – at the café on the border triangle it is possible to sip coffee while looking out over all three – but also to a remarkable range of top art galleries. If there’s only time to explore one, make it the Beyeler, a stylish modern building set in peaceful gardens only a short tram ride from the city centre with (among much else) a top-notch set of French Impressionists.

These cultural highlights can be washed down in enviable comfort, with A-list food and wine. Indeed, in keeping with Swiss tradition, one of the city’s most striking landmarks is a hotel: the Drei Könige (Three Kings) which overlooks Basel’s most important bridge. Napoleon held a carve-up Europe lunch here and dozens of other historic celebrities have passed this way: Goethe, Voltaire, Dickens, the Dalai Lama and the rest. I had a spectacular drink on the balcony, thrilling to the swirl of the Rhine below my feet, trying to glimpse the table where, reputedly, King Farouk of Egypt loved the crêpes Suzette so much he had them for breakfast, lunch and dinner.

And, racing beneath the bridge, I spotted something else: a couple of swimmers hurtling downstream clutching zip-up floats (for valuables) and surging towards the docks. This is one of the few places where the Rhine is swimmable, and it is a high-speed funfair ride. I wish I could say I dropped everything and jumped in, too, but I fear I merely carried on sipping my wine and admiring them from afar.

It is hard to forget the historical shadow over even this elegant view, because Basel is where the story of Nazi gold unfolded. In the 1990s, it emerged that Hitler himself had a Swiss bank account – by then worth $1bn.

There is a further snag: Basel is the exact opposite of cheap. On the contrary, the Swiss franc is so mighty that if you want to spend a week in the Drei Könige, you might have to flog your car. But anyone can have a cocktail on its terrace, and the guidebooks are full of more affordable options (all smart and clean). In one way this is the whole point. Switzerland wouldn’t be Switzerland if you weren’t marvelling at the view… and then at the bill.

Three Rivers: The Extraordinary Waterways that Made Europe by Robert Winder is published by Elliott & Thompson at £20. Order a copy at observershop.co.uk for £18. Delivery charges may apply

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy