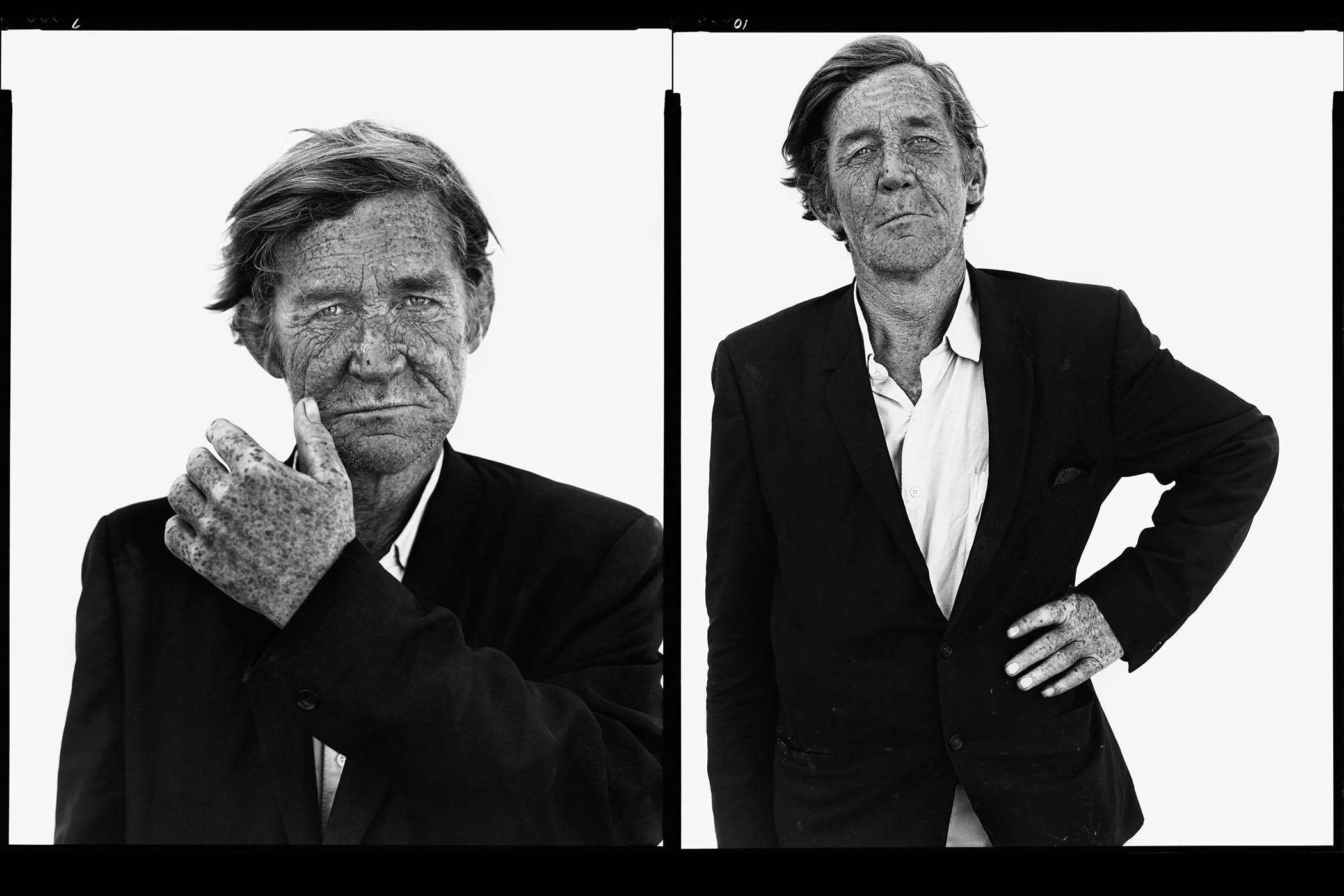

Portrait by Antonio Olmos for The Observer

Next to the entrance to David Henty’s house in Saltdean is a fading blue plaque that proclaims “The World’s Number One Art Forger”. The same legend is also on the calling cards, featuring a police-style mugshot of himself, that he gives to prospective clients.

In a kind of real-life chiaroscuro effect, the onetime villain has moved from the underworld into the limelight. An ex-convict turned self-taught painter, he developed his gift for imitating the work of well-known artists during one of his spells in prison. He went on to sell more than 1,000 forged artworks, mostly through eBay, before he was exposed in 2014.

Now a reformed character, his copies or works “in the style” of famous artists sell for between £5,000 and £50,000 to a clientele that includes financiers, gangsters and famous footballers. One buyer flew Henty in a private jet to Monaco so that he could replicate a genuine Picasso he wanted to protect from his hyperactive children. The crime writer Peter James used him as a model for a forger in his novel Picture You Dead. Later this month there is a full-scale exhibition of Henty’s work at the Washouse and Parlour Gallery in Rye called Twenty Old Masters and a Banksy.

For all this above-board success, the puckish 67-year-old savours his role as a spanner in the works of the art market. When I visited him last month, he picked me up from Brighton train station in his little convertible Abarth with its registration number of V9 OGH – Van Gogh, in case you missed the reference, is one of the many artists Henty has “done”.

In every room of his light-filled house overlooking the Channel there are Picassos, Lowrys, Monets, Modiglianis, Rockwells, Basquiats, Hirsts and Banksys leaning against the walls. The effect is a little as if a billionaire had recently moved into a suburban semi and hadn’t yet got round to hanging his collection.

He shows me around, picking out works here and there – “that’s a Picasso, did that in a morning” – and reveals a storeroom packed with either abandoned or unfinished paintings that haven’t quite come up to scratch. “I have to be the best forger,” he says. “I don’t want to be second. I’m never happy with what I’ve done. I always think: I could have done that better.”

Related articles:

What, though, does it mean to be best forger in the business? It’s a position that has no real analogue in other art forms. No one crows, for example, about being the most derivative novelist. And in rock music, tribute bands are seen as harmless but unworthy of attention. Of course, one of the key differences with visual art is that, because it’s collectable, it also forms a commodity market with all the dishonest manipulation to which such markets are prone.

One of Henty’s “Picassos” was valued at £1m at an auction in 2019, only for the forger to come forward and inform the auction house that it was his own work falsely attributed by an unscrupulous seller.

Almost by definition, forgers should be anonymous for the deceit to work. And they usually are, until suddenly they’re not. There’s a long history of fakers or forgers coming to public attention, most often after a police investigation, and then enjoying a second wind as legitimate copyists. In Britain we think of Tom Keating, a prodigious forger in the 1950s, 60s and 70s, who was put on trial at the Old Bailey for fraud but went on to have his own TV series and receive the ultimate accolade of his work being forged by others. More recently there was John Myatt, who made more than £250,000 by forging celebrated artists using a mixture of emulsion paint and KY Jelly.

Henty says his only notable current rivals are the Americans Tony Tetro and Ken Perenyi, but he suggests that Tetro, who also served time in prison, backed out of a TV show in which they were going to test their mimetic talents because he was intimidated by the Englishman’s abilities.

Henty’s painting The Cripples After LS Lowry apes the artist’s chronicling of industrial life.

If forgers tend to be dismissed by critics for their lack of originality, some experts suggest that much of the art on the market is forged or “misattributed”. In a 2014 report, the Geneva-based Fine Arts Expert Institute claimed the figure was as high as 50%.

Henty grew up in an environment of uncertain attribution. He was the eldest of six children of a Brighton antiques dealer who forged silver candlesticks and Victorian jewellery. His mother left the family home when Henty was young, and the domineering father spent much of his time with another family he had spawned elsewhere.

Henty and his siblings, he says, were left to bring themselves up. He describes his childhood, which sounds like something out of the TV series Shameless, as “feral”. His four brothers and a sister, all of whom have flourished as adults, apparently all demonstrated a creative bent in different ways. In Henty’s case, he started off by touching up paintings for his father, sometimes with a forged signature. The father would make money out of his son’s work, but Henty says he never saw any of it.

The profits only came when he graduated into other, more risky areas of crime. By his own admission, as a younger man Henty saw the law as a minor inconvenience that stood between him and riches. It was an attitude that landed him with a five-year sentence for forging passports in the mid-1990s, of which he served two and a half years.

He didn’t mind prison. “I can look after myself,” he says in a matter-of-fact way. This is no doubt true. He still practises kickboxing every week, which is where he met his wife, Natania, who insisted that he abandon his criminal past.

It’s hard, though, to imagine Henty ever getting into a scrap because he has such a disarmingly amiable manner. It’s not so much roguish charm – although that’s in the mix – as an infectious appetite for life in all its many shades and colours.

Peter James calls him “the nicest villain I have ever met”.

It probably explains why Henty is on good terms with the policeman who arrested him in the 1990s and with the Telegraph journalist who later exposed him, as well as retaining close connections with senior gangland figures and various other criminals.

“Actually, a friend of mine who’s a drug dealer is coming round this afternoon,” he says, reassuring me that his old muckers respect that he’s committed to a legit lifestyle.

Looking back he thinks it was the lack of distractions in prison that enabled him to focus on painting, at first watercolours. But it wasn’t as if his solitary artistic pursuits brought an end to his old criminal ones. After his release, he went on to be arrested again for forging log books in a stolen car scam that had brought in so much money that he was living in a Georgian house in the most expensive street in Brighton and had accrued hundreds of thousands of pounds in cash.

“I don’t know where it all went,” he says now. “I’ve always had a pretty lax attitude to money.”

He skipped his trial and went on the run to Spain, but was caught by the Spanish police and held for a year awaiting extradition. On his first day in a Spanish prison he witnessed a dispute between two members of feuding families.

“One stabbed the other in the leg and he died there and then,” he says, shaking his head at the bizarre memory of it all.

Despite that bloody beginning, he says he had “an amazing time” in the prison, not least because he met a Russian criminal who’d been to art school who helped to develop his drawing technique. He also, he says, befriended an Italian mafia boss called Vincenzo who was trying and failing to paint a picture of his wife. Henty took over and completed the portrait, and several more of the mafioso’s spouse.

He also painted a number of “Van Goghs” that Vincenzo managed to sell on the outside.

“We were making quite a good living,” Henty recalls.

Eventually he was repatriated to the UK, where, with half of his two and a half year sentence almost up, he served a brief stint in prison before his release. This time he was determined to go straight. What that meant in reality was staying marginally on the right side of the law. On the advice of a barrister friend, he would sell signed forgeries but with the caveat that he had no provenance or paperwork so, unfortunately, he could only say that they were in “the style of” or “after” the named artist.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

“For five years I was making so much money,” he says, once more laughing at the memory.

Then he was rumbled by the Telegraph, not once but twice, after which he finally realised that he could make a decent living doing what he does openly without any subterfuge.

One grey morning in Saltdean, I watch Henty apply careful dabs of oil paint to a copy of Caravaggio’s Judith Beheading Holofernes, which he’s working on in his sitting room. Nowadays he has a well-read knowledge of painting techniques such as tenebrism and impasto, in which Caravaggio excelled, but Henty is an intuitive painter who likes to work out an artist’s brushstrokes through copying their work. As a result he believes the great baroque artist was a “lefty”, even if experts are divided on the issue.

Caravaggio, who was renowned almost as much for his reckless lifestyle as his sublime works, is Henty’s hero. He says he didn’t know much about him until he went to an exhibition at the National Gallery a decade ago.

“I walked in and it was like being hit with a cricket bat,” he says. “I couldn’t believe this guy had done this. I couldn’t believe anyone could do it.”

He immediately set about seeing and reading everything he could relating to Caravaggio (as a prelude to his show in Rye, he is introducing Derek Jarman’s 1986 film about the artist at the local cinema). There is much scholarly disagreement about the artist’s life (was he gay or bisexual?) and death (was the cause malaria, syphilis or his enemies?), but most agree that he killed a young man in a fight, perhaps unintentionally, and had to flee abroad to escape a death sentence. Henty agrees that the outlaw reputation only further piqued his interest.

“I found an affinity with his story,” he says between brushstrokes. “I do quite a few different artists but there’s ones that go with my brush and ones I can’t do convincingly; they don’t come naturally. Funnily enough, Caravaggio doesn’t come naturally to me.”

Propped up against a wall a few feet away from where Henty holds his easel is a gilt framed copy of Caravaggio’s Supper at Emmaus, which Henty has viewed many times at the National Gallery. A businessman commissioned him to paint it for £50,000. After a downturn in his fortunes, the businessman never collected the painting, thus losing his £20,000 deposit as well as the work itself. It’s an impressive piece of mimicry but, even to my inexpert eye, obviously not by the great man himself: it is not quite finely detailed enough and it lacks the uncanny realism Caravaggio achieved in his most celebrated works.

To his credit, Henty doesn’t pretend otherwise. “I can get away with a Lowry but Caravaggio’s something different,” he says.

He says it presents a challenge some way beyond his comfort zone, which is why he is dedicating himself to the task of creating two original paintings that could pass for Caravaggios; it is thought that at least a hundred of the Italian’s paintings have gone missing over the centuries.

To reach the required level of verisimilitude, he is first warming up on Judith Beheading Holofernes before going to Rome to copy five Caravaggio paintings, including Crucifixion of St Peter and The Conversion of St Paul. When he does eventually paint the “new Caravaggios” they will be on canvases that date from the period (the turn of the 17th century) and done with oil paints that are a close approximation to those employed by the original artist.

It’s a large undertaking that, unlike the copies of Van Goghs or Picassos that he can knock out in a few days and sell for more than £10,000, will require a lot of investment in time and money without any guarantee of return. He hopes to sell the five copies for £50,000 each and the two “originals” for £75,000, with the money going to finance a film he wants to make about Caravaggio. Yet he says of his previous efforts to imitate the Milanese painter: “They don’t exactly fly off the shelves, let’s put it that way.”

I walked in and it was like being hit with a cricket bat. I couldn’t believe anyone could do this

I walked in and it was like being hit with a cricket bat. I couldn’t believe anyone could do this

Nonetheless, he sees the endeavour as “a journey of self-discovery”. Three years ago Henty learned that he had pancreatic cancer, very often a terminal diagnosis. He underwent a successful operation to remove the tumour but, in the process, developed sepsis that almost killed him.

While he was in hospital and his life in the balance, he learned that the price of his work suddenly rose: death may be the ultimate setback in life, but it’s often a lucrative boon in the art world. This amuses Henty, who has few illusions about what he calls the “wild west” of the art market.

Having survived two close shaves with mortality, he is keenly aware of life’s fragility, and that has filled him with a desire to explore the limits of his ability. I put a hypothetical question to him. If he were approached by a major art thief and offered £1m to copy a classic work that was to be stolen to go in the basement of a Russian oligarch and replaced with the forgery, would he do it?

“Yes,” he says, “because you want to test yourself, go up against the experts.”

A few weeks later, I remind him of his answer and he says, no, he wouldn’t do it.

On one of my visits, the Washouse and Parlour gallerist Wendy Bowker calls round. A forthright Liverpudlian, she is a former prison governor who enjoys trading stories with the ex-con. In the old days, she tells me, prisoners required a special voucher to receive visitors and they were issued sparingly. Much to her amusement, Henty told her that he got round it by forging them and trading the surplus with his fellow lags.

Bowker believes that many gallerists are aware that they’re selling forged or misattributed works, but they’re happy to stay quiet as long as they can make money.

“That’s the name of the game,” she says. “It’s a free market, they think. But I don’t like the idea of someone being duped; I want transparency.”

Henty nods and then tells a story about the legendary Dutch forger Han van Meegeren, who was thought to have conned buyers out of the equivalent of more than $30m in the 1930s and 40s. After the second world war, he was arrested on collaboration charges for having sold classic Dutch works to the Nazis, including a “Vermeer” acquired by Hermann Göring in return for more than 120 looted works. It was a capital crime. His novel and successful defence was that he had forged the works himself, and overnight his alleged treachery was recast as ingenious resistance.

Henty says that a few years ago he watched an episode of Fake or Fortune in which a painting at the Courtauld Institute originally thought to be by the half-forgotten 17th-century Dutch artist Dirck van Baburen was suspected of being a forgery painted by Van Meegeren.

An expert from the Courtauld expressed the wish that it was a Van Meegeren, recalls Henty, because, owing to his notoriety, that was a more exciting prospect – and so it proved.

The moral of that story is that the art world is mercurial, as subject to changing fashion as any other cultural sphere, and forgers can over time become more popular than the painters they copy. It’s highly unlikely that Henty’s Caravaggios will ever hang in the Courtauld, much less outshine the originals, no matter how much he hones his craft. But he has succeeded in making his own particular mark.

When I leave, he hands me a small street scene “Lowry”, complete with fake signature and date (1939) and tells me it’s a gift to keep. As I exit, I notice that the faux plaque has a line around its perimeter. It reads: “He Has Painted More Lowrys than Lowry”.