The $205m price was set, not when Sotheby’s principal auctioneer, Brit Oliver Barker, brought down his gavel after 19 minutes of frenzied bidding, but seconds earlier, when his colleague, David Galperin, set aside his mobile phone in defeat, ending a call with a mystery bidder. “That’s the sure sign,” Barker said in response, and smiled over at Julian Dawes, the man still on the line with his bidder.

“The Klimt, Julian, is yours,” Barker said. Dawes cupped his hand to whisper reassurance to his victorious client and the record-breaking deal was done.

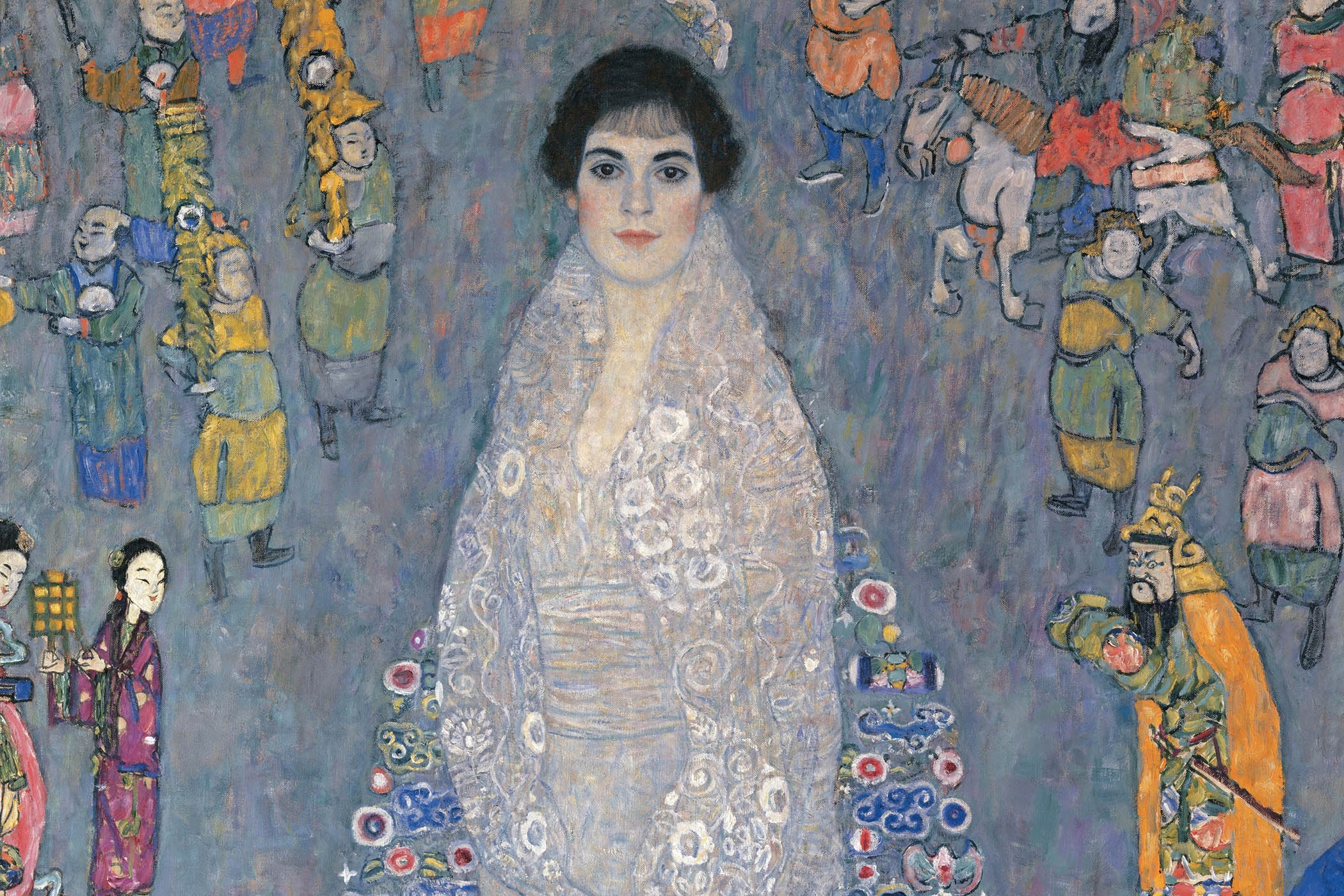

The historic moment inside New York’s Breuer Building last week concluded a six-way bidding war for Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer, a masterpiece painted in Vienna between 1914 and 1916, at the height of the city’s “golden age”. The painting is now the most expensive modern artwork to go under the hammer and the second most expensive from any era. The sale room price was the equivalent of £156m, but with buyer’s premiums and fees, the final cost is £180m. The deal was also a lifebuoy thrown out, not just to Sotheby’s, but to the art market in general and it is being seen as the symbol of a rising tide of hope. “It was one of those great turnaround moments,” says Helena Newman, an early player in bidding on the night.

The audience inside the sale room and its adjoining overflow area was full of Manhattan’s leading gallerists and collectors, including Larry Gagosian, the French dealer Philippe Ségalot, the Nahmad gallerists, Joseph and Helly, Christie’s former global president, Jussi Pylkkänen, the television impresario and art fan Ryan Murphy and the Israeli collectors in the Mugrabi family. Unusually, Patrick Drahi, the auction house’s telecom billionaire owner since 2019, watched in person from the back, exchanging glances with his chief executive, Charles F Stewart.

Melanie Clore, a previous chair of Sotheby’s Europe and co-founder of the art advisory business Clore Wyndham Fine Art, witnessed the drama: “One sensed this would be one of those paintings that would make an exceptional price, as it really appealed so widely, on so many levels, to various collectors and museums around the world,” she says. “It also looked amazing hanging in Marcel Breuer’s extraordinary building.”

The auctioneers had prepared the ground, most likely setting up third-party guarantees, known as irrevocable bids, to start the action. Newman, chair of Sotheby’s Europe, topped a leading bid for her client with an extra £5m before Dawes raised the stakes a couple of million more.

Then Patti Wong, Sotheby’s former Asia chairman, took the price to $140m. In the past she has bid on behalf of Rosaline Wong, a major Hong Kong collector with a love of Klimt. Onlookers gasped when Galperin, Sotheby’s vice chairman, suddenly jumped in with a phone offer of $171m. “There was a moment when it seemed it was going to sell at a certain level and then it went up again to $200m and there was applause,” recalls Newman.

Must the portrait now step back into the shadows, where it has already spent much of its life? “We all hope it will be seen, of course, but it is up to the buyer now,” says Newman. The new owner’s identity has not been revealed.

The painting’s subject was the daughter of Klimt’s biggest patrons, August and Serena Lederer, and it was sold from the estate of Leonard A Lauder, who died in June. For 40 years the Estée Lauder cosmetics heir had kept it in his Fifth Avenue apartment, dining daily under Elisabeth’s frank gaze.

‘One sensed this would be one of those paintings that would make an exceptional price’

‘One sensed this would be one of those paintings that would make an exceptional price’

Melanie Clore

Lederer now enjoys the status of Klimt’s other leading ladies, the glittering star of The Kiss and “the woman in gold” herself, Adele Bloch Bauer, subject of the looted portrait featured in the 2015 film starring Helen Mirren. Clore underlines the similarities in the backstories of the two portraits. Both were commissioned by wealthy Jewish patrons, the Lederers and the Bloch Bauers, and then seized by Nazi officials.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The Lederer portrait is one of few Klimts to survive the second world war. Long after the painter’s death in 1918 it helped to save the life of its subject. To avoid persecution as a Jew, Elisabeth pretended to be Klimt’s illegitimate daughter, offering the painting as evidence. Her mother signed a corroborating affidavit and Elisabeth was granted protected status as a result.

In 1938 the portrait was confiscated and didn’t resurface until 1985, when it entered the New York home of Lauder, a noted museum donor. Its singular history is now part of the painting’s persona and explains its remarkable price tag as much as its beauty does.

“That portrait was a last opportunity to buy something of such significance,” says Newman. “Klimt’s images go well beyond the art world, on posters and fabric, and standing in front of it I felt it had an absolute aura due to the depth of the shimmering colour. That is what drove the sale.”

Three other Klimt works from the Lauder estate also sold last week, going for close to their estimates at $86m and $68.3m, including fees.

As to who bought the Lederer portrait, suspicion hangs over the younger Lauder brother, Ronald, who in 2006 paid $135m for one of Klimt’s two portraits of Adele Bloch-Bauer and has hung it in his Neue Galerie in New York. Some market watchers think the portrait may have gone to a tech billionaire, perhaps even Jeff Bezos, or someone riding the AI boom. The American hedge fund manager Kenneth Griffin, an active buyer lacking a Klimt, is also in the frame, although some think he may have been the bidder on the phone who lost out at the last. Also in keen contention is the Abu Dhabi sovereign wealth fund, ADQ, which now has a stake in Sotheby’s and is opening a Guggenheim museum outpost next year. Tellingly, it was Dawes, the same Sotheby’s man on the phone to the winning bidder, who often represents the auction house in Abu Dhabi.

Whoever took the prize, Sotheby’s is celebrating a sale that may signal the end of a rocky time that pressured it into diversifying into pop memorabilia. The cachet of securing a sale price second only to that of Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi, painted circa 1500, which went for $450.3m in 2017, is coupled with the satisfaction of an evening that generated a total of $706m, the highest achieved at Sotheby’s on a single night. Over a past year in the art market has contracted as much as 12%, according to a survey by Art Basel and UBS, collectors have stayed out of the market and auction houses have retrenched.

Kenny Schacter, the irrepressible New York artist, writer and sometime dealer, is not surprised by the upturn. “I’ve been saying for six months that the art market is in rude health for the right material,” he says, “but that didn’t rate for clickbait. Between the Paris fair and auctions and New York sales, the sentiment has finally caught up with what I’ve seen in the trenches for months.”

Shachter would also approve of a distinction made by Newman, who describes the record-breaking sale “as making art market history". On Tuesday Shachter had been quick to knock back a social media post from the Mexican French artist Alexis de Chaunac, who hailed a moment of “art history” made inside the Breuer building. “Art history does not happen in the salesroom”, countered Shachter.

Image by Sotheby’s via AP