British Museum, London WC1; until 7 September

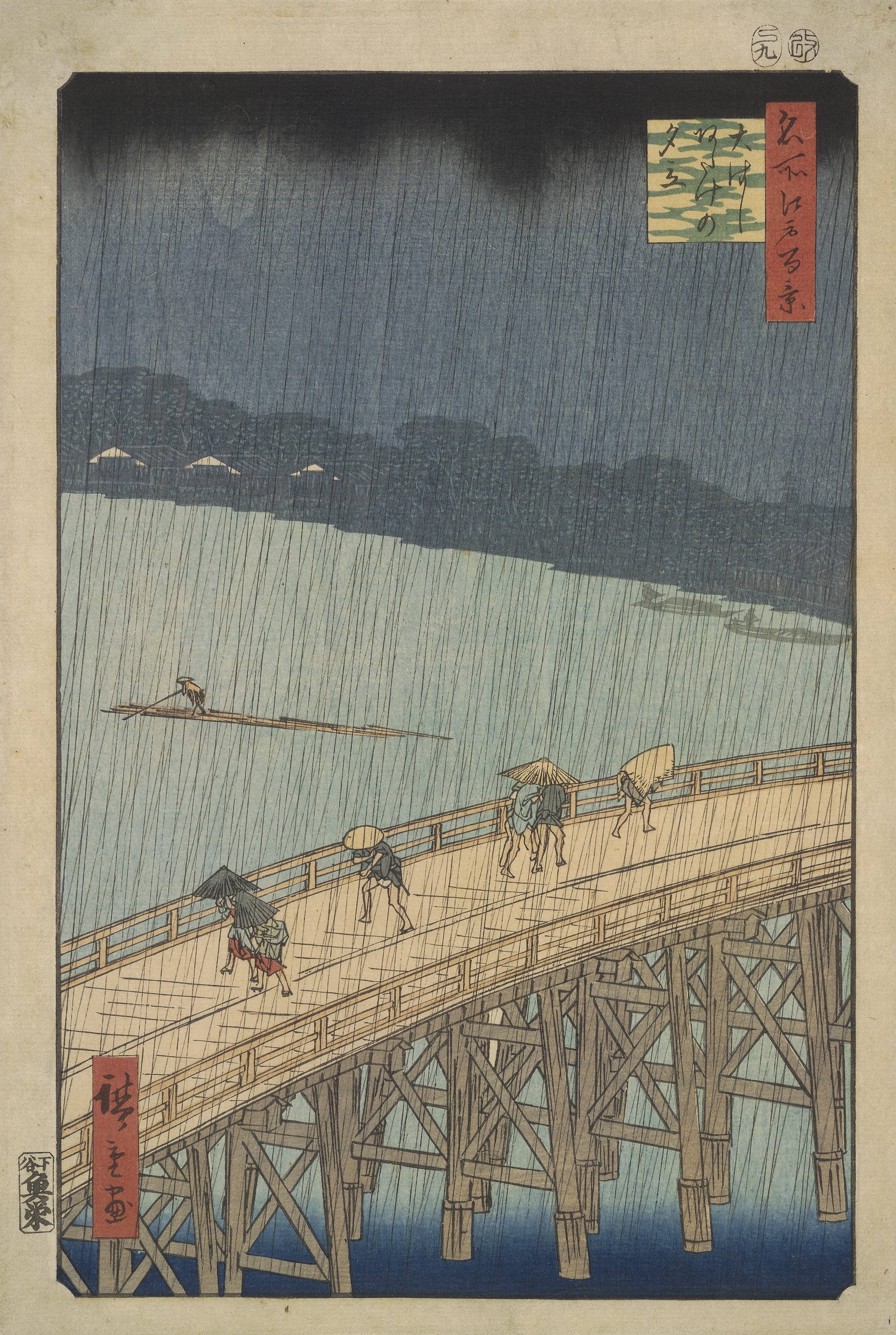

Hiroshige’s mesmerising image of a sudden shower over a Tokyo bridge depicts rain as torrential yet mysteriously static in a downpour. The print is a famous graphic feat. A black band at the top represents both outer space and darkening rainclouds unleashing their burden; the river below runs pale with a billion flashing drops. Figures dash across the bridge, trying to dodge the needle-sharp striations cut into the woodblock. One has come out without an umbrella to his name – a tiny sight gag in a vision of how it looks and feels to be caught in the rain.

A great exhibition can change our sense of an artist’s mind for a generation – and so it is with this one. The British Museum puts Hiroshige’s humanity to the fore. The show opens with his portrait: bald, sharp-nosed, acutely intelligent, humour creasing his eyes. Four colleagues collaborated on this image after the artist’s sudden death, possibly from cholera, in 1858. Born in 1797, he survived into the camera age, and into the lifetime of so many western painters who loved his work, from Whistler to Monet and Van Gogh. But there is no sense in which Hiroshige’s art could mean quite the same thing to them as it did to the Japanese.

You can almost hear the figures gossiping, laughing, carping at one another

You can almost hear the figures gossiping, laughing, carping at one another

The open road of the title is exactly the point. To the west, this relates to Hiroshige’s gift for composition; the way he opens up a vista, leading the eye along winding roads, receding highways, round the bends in a river. Previous shows have concentrated, too, on his atmospheric genius – vaporous mists, moonlight on water, the way haze and haar unfurl through a print. But this exhibition is the most comprehensive in decades. It gives you Hiroshige as a traveller, too, passing along the open roads from Edo (now Tokyo) to Kyoto, as the most popular Japanese artist of his day.

What Hiroshige shows is Japanese leisure and pleasure. His figures are sightseers, wanderers, pilgrims, geishas. They take trips to see weirdly shaped islands, to view cherry blossom, snowfall and the distant circumflex of Mount Fuji. They go in crowds of 20 to gawp at a gorge, or a hundred to visit a rocky shrine. If Japan was isolated from the west until Commodore Perry’s 1853 incursion, it was entirely open to itself. Mass tourism materialises in these prints.

Viewing was, and remains, a ceremonial end in itself. But it always feels as if Hiroshige is right there among noisy people. There is a brilliantly unexpected scene of families going out to watch nightfall and listen to the insects, one man turning to the rising moon, another with his head down, trying hard to hear any kind of buzz. A courtesan lounges on a balcony, viewing Fuji with nonchalant teacup in hand. And Hiroshige’s 1832-34 snow-viewing triptych is hilarious.

Careful – don’t slip! It is too cold for all this. A girl prods the snow with her parasol: how deep is it anyway? The snow (or is it the print) beautifully transforms the nearby cityscape into a frozen white garden, but Hiroshige creates a comedy in the silence simply through body language. You can hear his figures gossiping, laughing, carping at one another.

It is no surprise that Hiroshige was a hiker, his eloquent diaries giving us the daily route. A contemporary of Caspar David Friedrich, his vision of nature is not particularly romantic or even delicate, so much as robustly knowledgable. His figures walk the roads, work the fields, pole the rivers, pass the sake. They struggle against autumn winds, fan themselves in city summers, pick their way through winter in nothing but stubbornly fashionable clogs.

Related articles:

The last great ukiyo-e artist, Hiroshige was as prolific as he was popular, leaving an estimated 8,000 woodblock prints. He made them for freshly cleaned homes at New Year and for bamboo fans in high season, to be junked after the summer’s heat. These fan prints are priceless today partly because they were so disposable. The democratic nature of Hiroshige’s art is visible, still, in fractional creases in these paper prints in their glass cases at the British Museum, masterpieces once sold to urban workers for not much more than the price of a bowl of noodles.

His colours remain vigorous: strong Prussian blue, newly imported from Holland, running to cobalt and turquoise, cherry-red for sunsets and dawns, forest green and glowing yellow for landscapes under hot skies. A whole print can turn on one colour. A white rabbit gazes up at the moon, a single pink dot for an eye, above a deftly drawn smile and whiskers; this scene is Japanese Beatrix Potter.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Hiroshige is broader, more exuberant and witty than one knew. Much is made of his calm and steady views in this show, but there is irrepressible energy beneath. People crack jokes, remonstrate with one another over dinner in a floating restaurant, light pipes in the dangerous embers of a bonfire. Boys lark about with pet dogs and a chubby child beams at her mother, both of them up to their sturdy knees in water. It’s a Japanese seaside postcard.

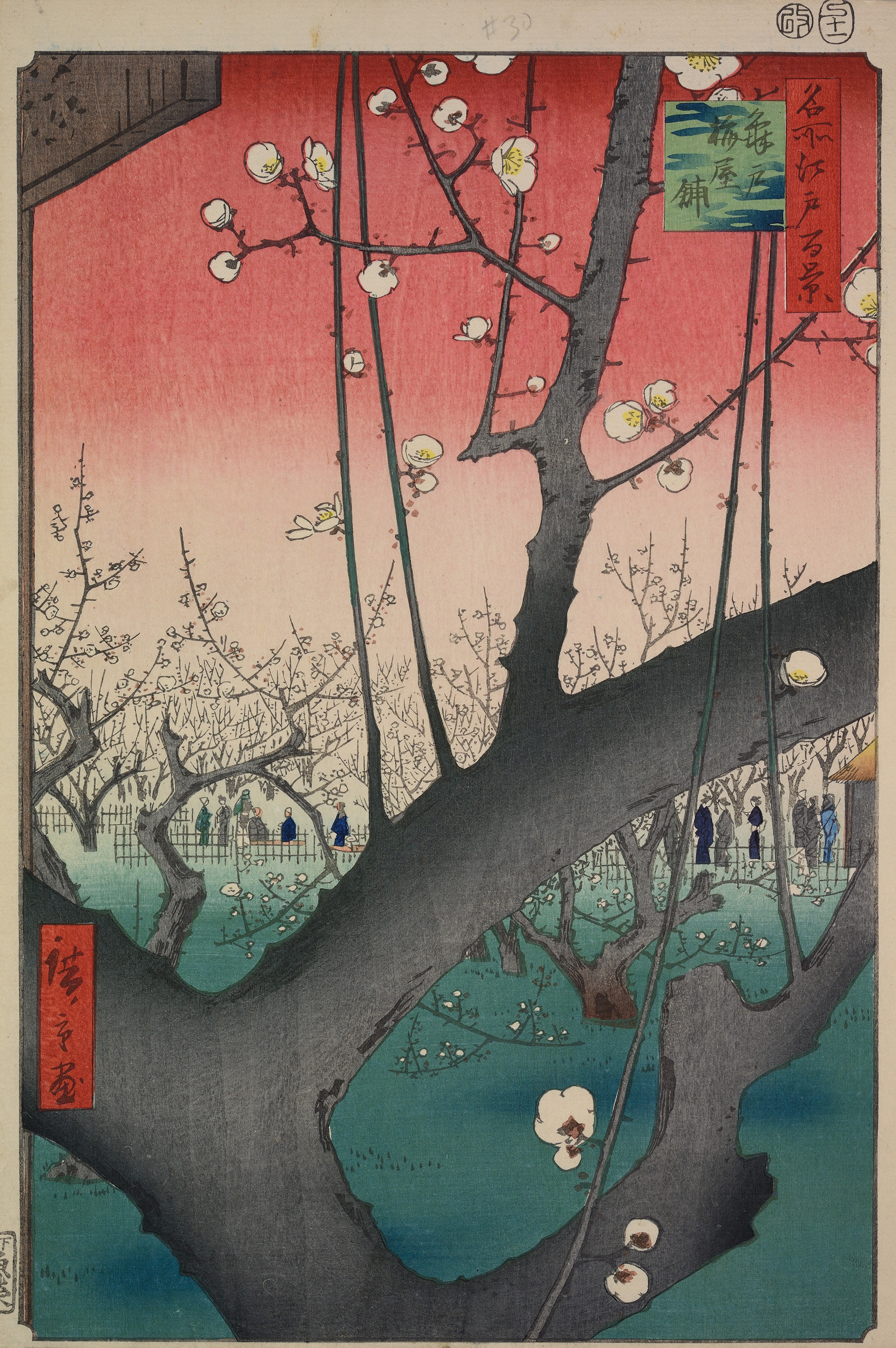

How Hiroshige puts a picture together changes over time, from horizontal to vertical and from open road to complicated closeup. A cockerel’s scarlet crest is visible only through a lattice of black feathers. A cricket is concealed, hide-and-seek, in morning glory. The famous carp banner hangs huge, and close, above a miniature Fuji, and tiny scatterings of tin-tack marks stand for grass, trees or even harvest fields. If this makes you think of Van Gogh’s extraordinary ink notations, the connection is made explicit with the inclusion of one of his landscape drawings and the very print Van Gogh owned of Hiroshige’s Plum Garden at Kameido, the wild drama of its foreground tree obscuring distant figures admiring the blossom.

Hiroshige takes the drama of cranes circling against a pale disc of sun or birds flying up from the spume of a wave further still into the realms of depiction. He describes the way we see the world, near and far. Sailboats on a limpid blue ocean are shown as small white rectangles, outlined in black except for the lower edge, where they simply disappear into the water. Foregrounds vanish altogether to imply an infinity of rolling air. People start to disappear from his art and nature takes precedence. The late prints are so tall and narrow they could almost be scrolls, empty of everything except a shadowy peak or fir tree. A last waterfall cascades right out of the bottom of a print as if art had no limits. Sightseeing of another kind has taken over.