In February 1965, one of the most electrifying public debates of the postwar period took place at the Cambridge Union. The motion, “Has the American dream been achieved at the expense of the American Negro?”, pitted two Americans against each other: the black writer and activist James Baldwin and the nation’s leading conservative, William F Buckley Jr.

The debate illuminated the depth of the fissures that rent 1960s America. Baldwin – whose book The Fire Next Time had recently been published – spoke to, and from, the nation’s moral conscience, at a time when both he and America were wrestling with their demons, and when the country seemed on the edge of catastrophe, being ripped apart by hatred and violence. Buckley was a seasoned speaker and debater, but he was no match for Baldwin’s righteous eloquence. Baldwin, speaking for the motion, humiliated Buckley, winning on the night by 544 votes to 164.

From today’s perspective, the debate illuminates the degree to which American conservatism has shifted in the last 60 years. Buckley was a key architect of the postwar conservative movement, helping unite anti-communists, free marketeers and social conservatives – the fabled “three-legged stool” – into the coalition that eventually propelled Ronald Reagan to the White House in 1980. He founded and edited National Review, for many decades the intellectual anchor for the movement, and which Buckley used to mould a more reactionary Republican party. He defended apartheid in South Africa and segregation in the deep south, insisting in a notorious editorial in 1957 that Jim Crow was necessary because whites were “the advanced race”. He opposed the Civil Rights Act, though he later changed his mind both about segregation and civil rights. He advocated the use of nuclear weapons in Vietnam. He believed that the poor and poorly educated should be denied the vote. His first book, God and Man at Yale, published in 1951, accused university professors of indoctrinating students with liberal and godless ideas – an early outing for what has become a familiar argument. Little wonder that many view Buckley as the precursor to Donald Trump. “He’s the founder of the movement we have today,” Sam Tanenhaus, author of an exceptional biography of Buckley, told CBS.

The irony, though, is that Trump’s Maga movement has been built on the repudiation of the Buckley-Reagan Republican party. Maga retained the old social conservatism, deepening it, and many have come to view “woke” as a communist ideology, yet it scorns Reaganite neoliberalism, globalisation and the acceptance of the US as the guarantor of international order, fashioning instead a different three-legged stool: hostility to immigration, support for economic nationalism, and an America-first foreign policy. For many contemporary conservatives, the trouble with Buckley is that he was insufficiently illiberal.

There have been many books trying to make sense of Maga and understand how it came to eat the Republican party, such as John Ganz’s When the Clock Broke and David Austin Walsh’s Taking America Back. The latest is Laura K Field’s Furious Minds, which seeks to comprehend the intellectual foundations of the “Maga New Right”. Many liberals, as Field herself notes, snort at the very thought of an intellectual account of Maga: “Trumpy intellectuals? Now that’s all oxymoron!” Such dismissal, she observes, not only fails to understand the importance of ideas to the conservative project but also “overestimates liberalism’s immediate appeal and underestimates liberalism’s fragility”.

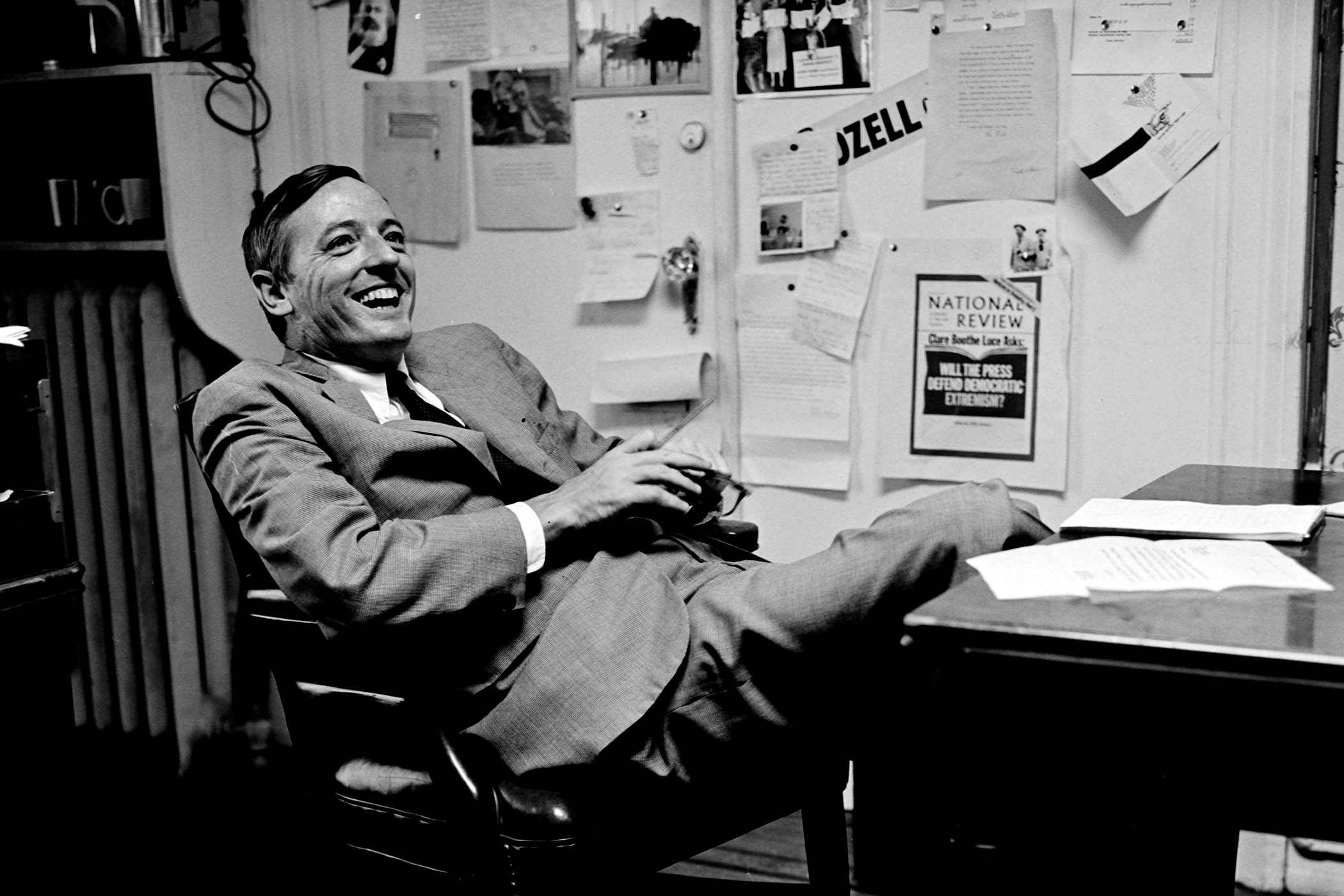

Above: National Review editor William F Buckley Jr in 1965; main image: Donald Trump hands out Maga hats during a rally in Pennsylvania, November 2020.

Field is well placed to write such an account. While not a conservative herself, she has been “steeped in the world of conservative intellectualism”, being trained academically by figures close to the Maga New Right, in particular followers of Leo Strauss. The German-American political philosopher has become a totemic figure among conservative thinkers for his critique of modernity and of liberalism as opening the way to relativism and nihilism, and for his embrace of the classical political philosophies of ancient Greeks, and of medieval Christian and Judaic thinkers. Strauss is known, too, for his theory of “esoteric writing”, the belief that philosophers concealed secret truths within their published works, an argument that New Right thinkers have seized upon, and which inevitably greases the wheels of conspiracy theories.

Field divides the intellectuals behind the Maga New Right into three main groups. The first are the “Claremonters”, associated with the Claremont Institute thinktank in California, who “idolise the American founding” (which they insist was rooted not in liberalism as commonly accepted but in premodern ideals) and are steeped in Strauss’s work.

They are the most Trumpian of the New Right intellectuals, and the most apocalyptic. In 2016, the institute’s Michael Anton published, under the pseudonym “Publius Decius Mus” – assuming an ancient Roman identity is a common affectation on the New Right – an article in the Claremont Review of Books entitled The Flight 93 Election. In it, he histrionically compared that year’s election to the hijacked plane on 9/11 that crashed into a field in Pennsylvania, killing everyone on board, after the passengers heroically stormed the cabin – preventing an even greater tragedy had the plane reached its intended target in Washington DC. American electors, Anton wrote, had to “charge the cockpit or you die”. Voting for Trump may seem a tad less heroic than battling Al-Qaida hijackers, but for the hard right the comparison made sense. The shock jock Rush Limbaugh read out the whole article on his show, transforming it into a national sensation. Anton was rewarded with a job in the new Trump administration.

Four years later, John Eastman, director of the institute’s Center for Constitutional Jurisprudence, became the intellectual cheerleader for Trump’s outlandish claim that he had won the election and that Joe Biden’s victory was fraudulent. He was disbarred by the state of California and faced criminal indictments in Georgia and Arizona, eventually being pardoned when Trump returned to power.

The second main cluster of New Right intellectuals are grouped around the National Conservatism movement, founded by the Israeli-American political theorist Yoram Hazony, a former adviser to Benjamin Netanyahu. NatCons are hostile to globalisation and their nationalism is less civic than ethnic and often rooted in religion. Theirs is a movement that reaches out well beyond America. They laud Viktor Orbán and view Hungary as a model of civic health. Orbán’s authoritarianism seems only to add to his lustre.

Claremonters are the most Trumpian of the New Right intellectuals and the most apocalyptic

Claremonters are the most Trumpian of the New Right intellectuals and the most apocalyptic

The third group on the New Right are the postliberals. In America, they tend to be Catholic intellectuals (postliberalism has a somewhat different texture in Britain). Their stars include Patrick Deneen, author of Why Liberalism Failed and Regime Change, the former receiving international attention when Barack Obama placed it on his list of favourite reads in 2018; Sohrab Ahmari, the founding editor of the online magazine Compact and the instigator of an infamous or celebrated (take your pick) spat with fellow religious conservative David French, in which he accused French of being insufficiently socially conservative and, in common parlance, of lacking bottle; and Adrian Vermeule, a professor at Harvard Law School and perhaps the most abrasive of the postliberals.

Postliberals can be both the most extreme and the least Trumpian of the New Right, their hostility to liberalism running deeper than that of the Claremonters and the National Conservatives. Deneen’s answer to “why liberalism failed” is “not because it fell short, but because… it has succeeded”. Liberalism’s very success dissolved the institutions, networks and philosophies necessary to uphold morality, trust and order.

For Deneen, the “liberation of women” has not emancipated them but rather placed them in a “far more encompassing bondage” – that of “corporate America”. Deneen reveals the postliberal distaste both for liberal ideas of freedom and for the depredations of the market. Postliberals, Field suggested in an interview, “are almost open to socialism”. That they are not, though all are critical of capitalism. Their solution is a society in which the exploitation of workers is ameliorated in the name of the common good. Deneen, in Regime Change, demands the creation of a new elite capable of inculcating the lower orders with an “understanding of what constitutes their own good”. This he calls “aristopopulism” – populism with a feudal touch.

Beyond these three main groups lies an amorphous mass that Field calls the “Hard Right Underbelly” – a group that revels in saying that which is unsayable even to most Claremonters, NatCons and postliberals. Often adopting pseudonyms such as “Raw Egg Nationalist” and “Bronze Age Pervert”, they can be poisonously racist and intensely misogynistic. Many within the Claremont and NatCon circles are happy to welcome them, but postliberals are often critical, Ahmari denouncing them as the “barbarian right”.

There are deep differences within and between the various factions of the New Right. What they have in common is a hatred of liberalism and a despair of modernity. As more liberal strands have been crushed within American conservatism, so the reactionary elements, writes Field, have “ascended unambiguously to the centre of power in the Republican party”.

Furious Minds is an outstanding intellectual history of the present. Such histories carry with them, though, their own methodological baggage. Field perceptively teases out the various strands of the Maga New Right but does not locate them within a broader history. It is striking, for instance, that Alasdair MacIntyre, who in the late 20th century virtually laid the philosophical foundations of postliberalism through works such as After Virtue, does not get a mention. Nor does Field relate the intellectual streams to the wider political, social and economic developments that lie beneath popular disenchantment with liberalism and globalisation and have aided the rise of populism.

It is not a criticism of a book that it keeps narrowly to its subject. Nevertheless, to truly understand the intellectual currents that Field so astutely dissects, one needs also to broaden the perspective.

Furious Minds: The Making of the Maga New Right by Laura K Field is published by Princeton University Press (£30).

Photographs by Brendan Smialowski/AFP via Getty Images, Nick Machalaba/Penske Media via Getty Images

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy