If Britain’s relations with the European Union (EU) are at all a hidden history, then they have very much been hiding in plain sight. This is the issue that has dominated our politics for almost a decade, to the exclusion of almost all other (more interesting and more important) subjects. Yet, from the prologue of this book, which opens in 1943 – when we meet Harold Macmillan (the new minister for North Africa) at Allied Headquarters in Algiers along with Robert Murphy (the US charge d’affaires to the Vichy government), Charles de Gaulle (leader of the Free French) and Jean Monnet (a French industrialist) – the author Tom McTague makes an old story new.

He does, of course, update that story. McTague, the recently appointed editor-in-chief of the New Statesman, has, in a sense, written the next chapter to Hugo Young’s This Blessed Plot, only he has done more than that. Where Young’s text is full of ex cathedra assertions about the cowardice of politicians who fail to measure up to his own severe pro-European standard, McTague is much more even-handed and his book is all the more serious for it. He takes his title not from Shakespeare but from TS Eliot, from Little Gidding, the last poem of his Four Quartets, in which Eliot meditates on the mythic distance inspired by the sea.

This is the story of Britain in Europe, told through our fabled national characters. McTague has had some criticism for not applying a European lens to his story but that is unfair. He has chosen to write from the vantage point of Britain, which naturally produces a kind of historical imbalance, but this is the tale he has chosen to tell and he tells it well. He is interested in the ideas behind the politics and he cares about the rhythm of a good sentence: two virtues that are rare in those whose apprenticeship has been served in the press pack of British politics. Indeed, the book declines in quality as it goes on; the closer we get to the present day, the more irrelevant the detail, the cloudier the perspective.

Most of this book benefits from the fact that McTague cannot talk to Macmillan. Halfway through an exhausting account of the formation of Business for Sterling, I wished Dominic Cummings had made himself unavailable too (though not in the same way).

But the main arguments one might have with this book are substantive, which is to say that I did not always quite agree with McTague’s thesis, even as I enjoyed it. He argues that David Cameron’s decision to call the 2016 referendum was his way of making Britain face its contradictory impulses on Europe, which is generous to say the least. He also casts the referendum decision itself as a verdict on an unstable relationship. I share with McTague the conviction that people had their reasons for voting to leave, which ought not to be traduced, but that doesn’t mean they add up to a coherent position on the EU. In truth, for most of the period under scrutiny, the British people hardly had an opinion either way on its complexities. There is a story to be told about why the political class managed to get so obsessed by an institution that barely featured among the concerns of the public.

Perhaps the really hidden story of the EU is that it has always been slow and a bit hopeless

Perhaps the really hidden story of the EU is that it has always been slow and a bit hopeless

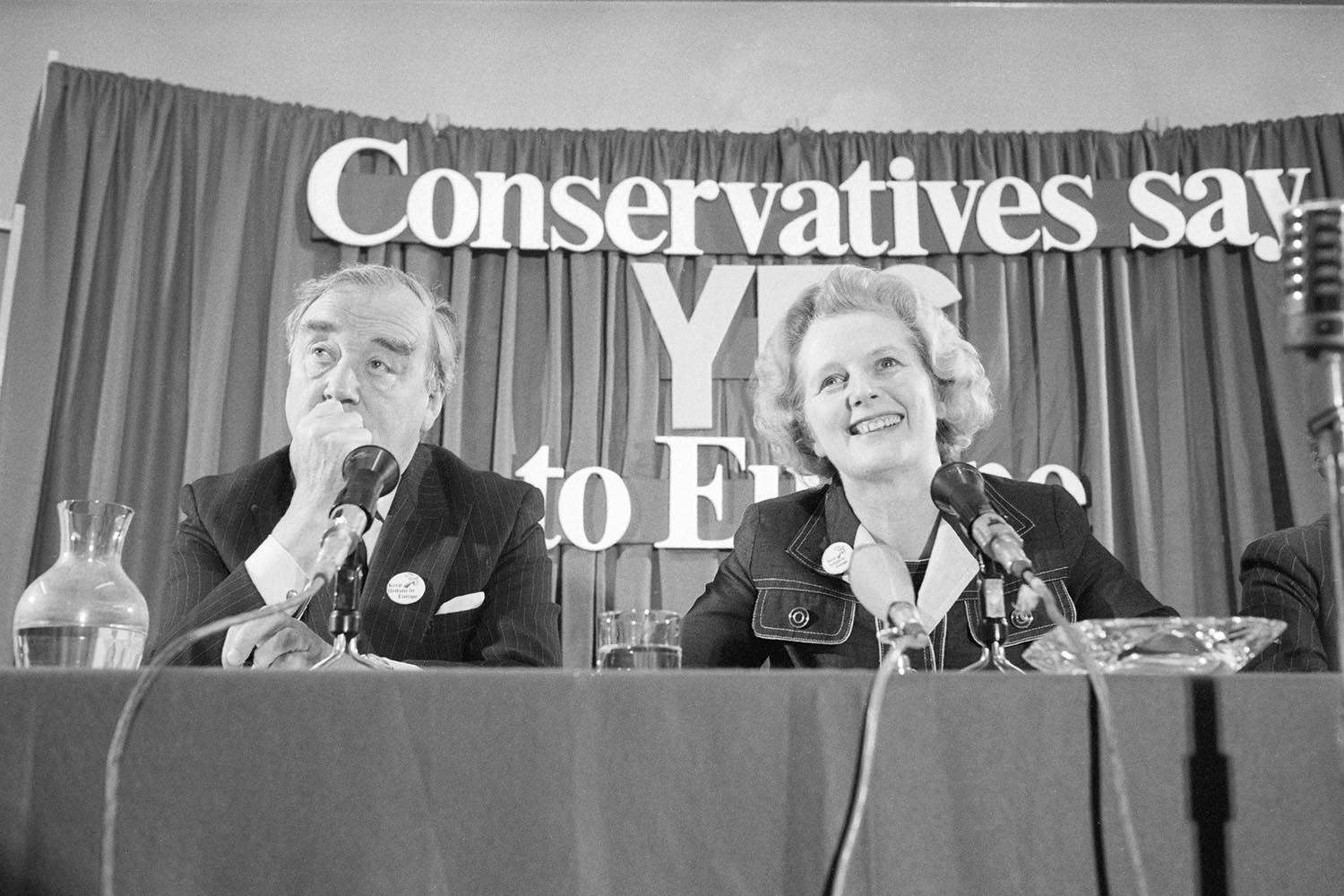

Perhaps there was a sort of conservative wisdom in the lack of clarity of Britain in Europe. Ever since Britain declined to sign the 1957 Treaty of Rome, which created the European Economic Community, relations between Europe and its largest island nation have been difficult. Britain’s applications to join were rejected in 1961 and 1967, before entry was permitted in 1973. A referendum on whether Britain should remain in the EEC was held in 1975, with the winning “Yes” campaign supported by both the Labour prime minster, Harold Wilson, and the newly installed Conservative leader, Margaret Thatcher.

McTague writes that Britain’s leaders never quite told the public the truth about the desire for integration that animated the European project. But perhaps the really hidden story of the EU is that it has always been slow, cumbersome and a bit hopeless. It is true that its core mission was closer integration, but that doesn’t mean to say it was set to succeed. The idea of a single government had always been unlikely, but the 1995 enlargement sponsored by then British prime minister John Major – which brought Austria, Finland and Sweden into the fold – surely made it hopeless. Maybe the special position that Major negotiated – in but a bit out – with our opt-outs on the euro and Schengen, was a clever deal. Better than being out but looking in, which is where we will end up.

But this is to take up the argument that McTague presents, and the fact that I did so willingly and spent so long with a subject on which I thought I had heard enough is testament to his writing. This is a serious and weighty book from a man with a future in the writing of the past.

Related articles:

And the story of Britain and Europe is not over. In Little Gidding, Eliot advises – or perhaps warns – us that: “What we call the beginning is often the end / And to make an end is to make a beginning.” As the poem unfolds, the poet meets a ghost at dawn and is made aware of his follies and shame at his past deeds. There is work for McTague to do yet.

Between the Waves: The Hidden History of a Very British Revolution 1945-2016 by Tom McTague is published by Picador (£25). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £22.50. Delivery charges may apply

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Editor’s note: our recommendations are chosen independently by our journalists. The Observer may earn a small commission if a reader clicks a link and purchases a recommended product. This revenue helps support Observer journalism

Photograph depicting Margaret Thatcher and deputy of the Conservative party William Whitelaw during the 1975 referendum courtesy of Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images