John Pendleton was born in Chesterfield, Derbyshire, in 1848. By the time he died in 1926, he had enjoyed a career largely in newspapers, working as a subeditor for the big regional dailies in Yorkshire and Manchester. He was also a keen local historian, writing two books about his native town and county. And there his legacy might have rested but for the dogged detective work of British fantasy author Johnny Mains.

In 2018, Mains uncovered a third strand to Pendleton’s life – one lost to history: he was a writer of ghost stories. And almost 100 years after his death, Pendleton’s eerie tales are being read for the first time since they were published over more than a century ago.

Christmas has become a time for ghost stories, for which we can partly thank Charles Dickens, as well as the BBC’s beloved A Ghost Story for Christmas series. Originally broadcast in the 1970s, with new adaptations since 2005 – latterly directed by Mark Gatiss, including this Christmas Eve’s The Room in the Tower – these yarns have cemented the festive season as a time for chilly tales filled with dark shadows.

The BBC series mines the classic era of ghost stories, predominantly Montague Rhodes – MR – James’s scholarly early-20th-century tales, originally penned by the provost of King’s College, Cambridge to entertain his friends each Christmas Eve. It has also adapted stories by writers including Arthur Conan Doyle, Edith Nesbit and, this year, EF Benson – all of them mainly known for genres other than ghost stories.

But what of Pendleton? Or his contemporaries Lettice Galbraith, Mildred Clingerman and Mrs ET Corbett? Or the mysterious writer credited only as JYT, who wrote a wonderful Christmas story called The Ghost of Appledore Pool for a Devon newspaper, but who remains unknown? Until now, the biggest contributors to the great tradition of ghost stories have been lost to time.

Rufus Purdy, editor of Tales of the Weird

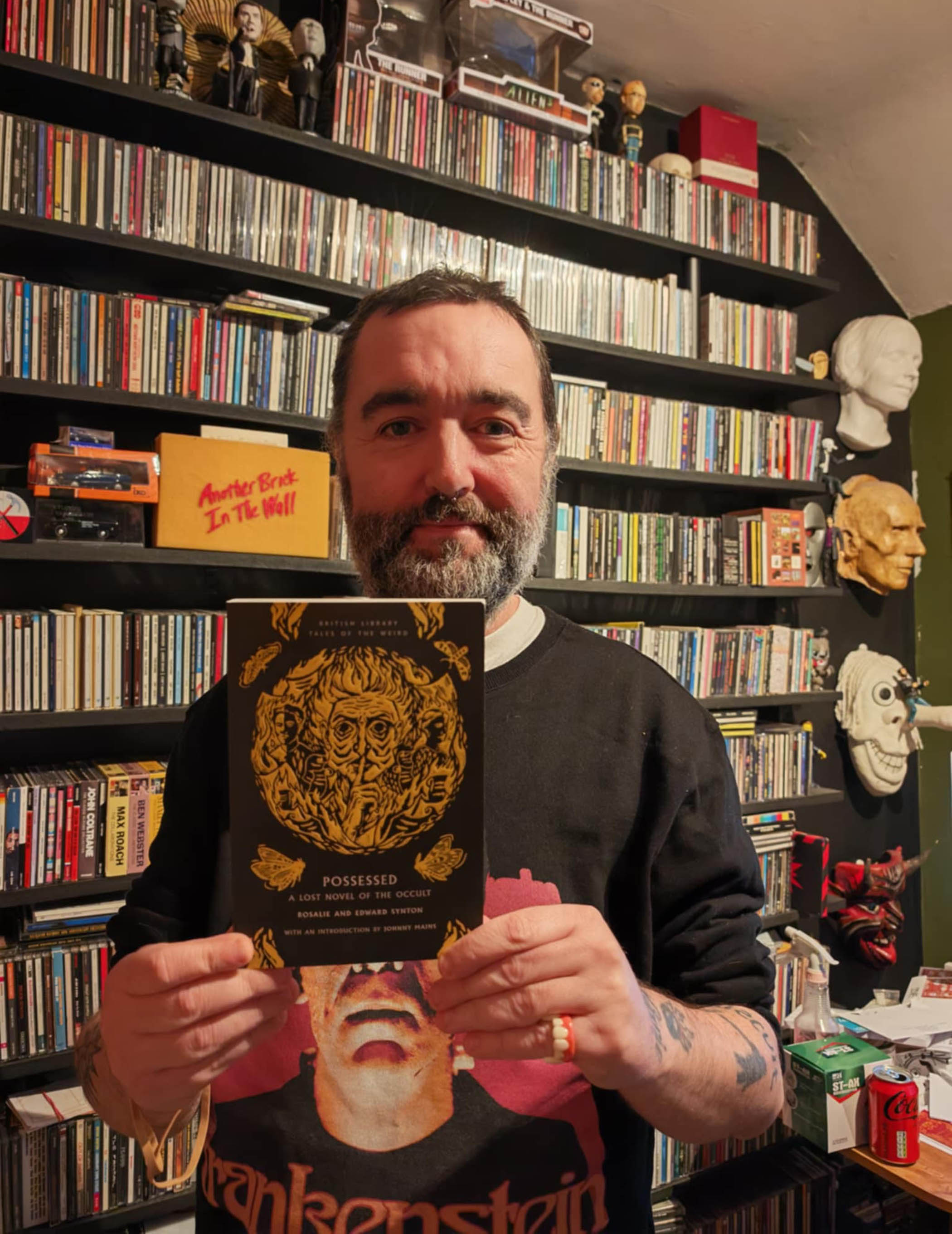

That changed with the discoveries by ghost story hunters such as Mains, an affable Scotsman born in the Borders 49 years ago and now living in south-west England. Mains is one of the British Library’s team with the task of tracking down lost or forgotten tales from the past.

The project is part of the work of the Tales of the Weird, a series of books published by the British Library that now numbers almost 70 volumes and puts out a new book every month through its subscription service. Volumes are grouped geographically – Cornwall or East Anglia, say – or by author, with collections devoted to writers such as Algernon Blackwood, Ambrose Bierce and Mary Elizabeth Braddon. Most inventive, though, are the anthologies organised by themes such as “botanical gothic”, “haunted forests”, “insect weird” and “the uncanny gastronomic”.

Mains recently edited a volume of stories entitled Illusions of Presence: Lost Christmas Ghost Stories. All but one had not been seen since publication, including the Pendleton story In Deadly Peril. But how do Mains and fellow anthologists Edward Parnell, Katy Soar, Mike Ashley and Melissa Edmundson actually find these hidden gems?

Related articles:

Apparently, it’s good, old-fashioned scholarly detective work. “I have access to newspaper archives across the UK, America, Australia,” says Mains. He also trawls bookshops and the internet, looking for ancient volumes and periodicals. He will buy up collections of half-forgotten magazines going back to the 19th century and old book catalogues from long-defunct publishers. “It’s a case of going through them, and searching the newspaper archives using certain keywords.”

For Mains, the wealth of regional newspapers that once provided overlapping, blanket coverage of the British Isles is where the real gold is. In fact, he says: “It’s the last big frontier for finding stories like this.” Nearly all newspapers used to regularly print fiction, and with the hot metal type melted down after each use to be remade, and the papers themselves the next day’s fish and chip wrappings, the existence of these tales was as fleeting and ethereal as the phantoms they often featured.

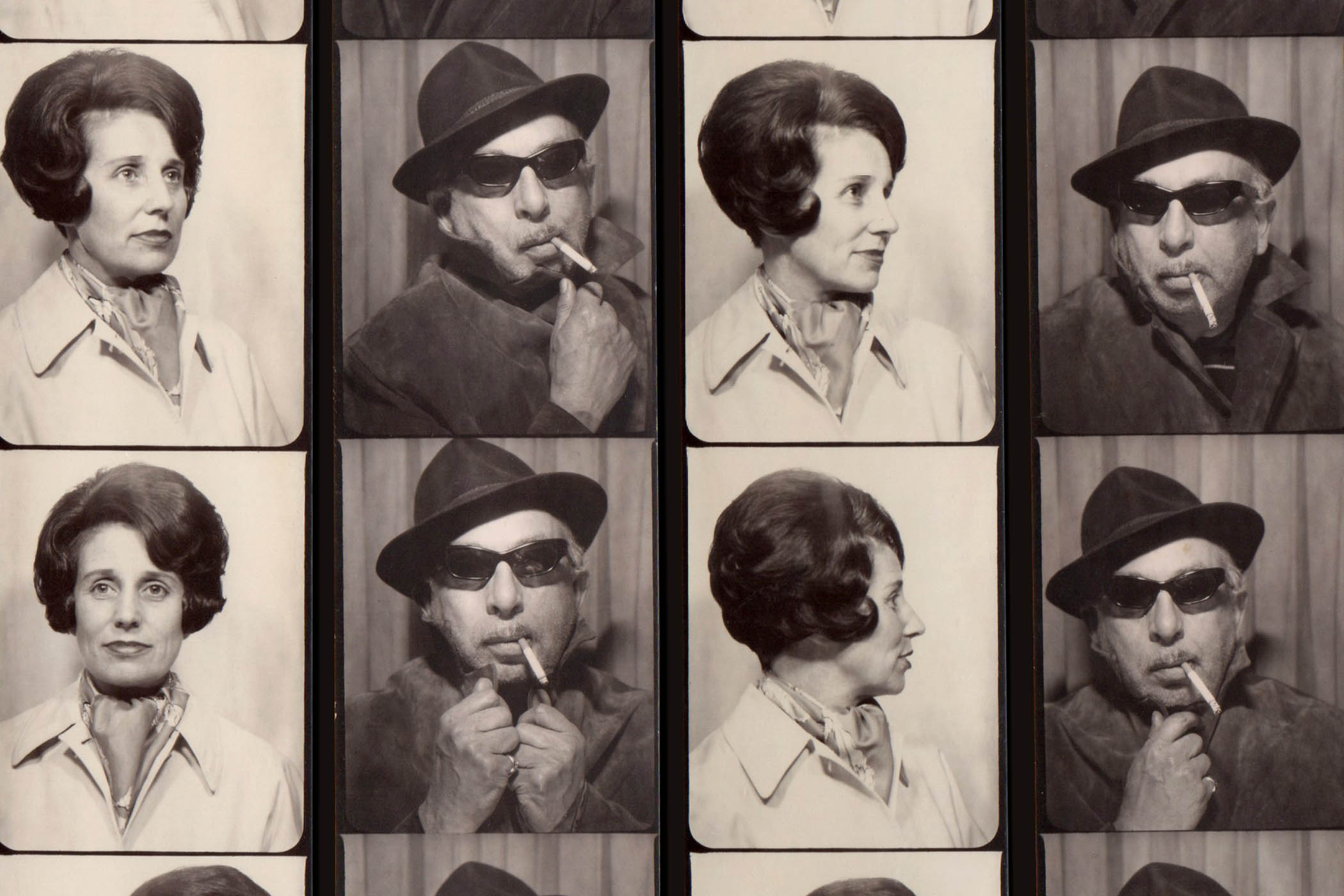

Violet Hunt, author of two early 20th-century collections of short ghost stories

Mains found the Pendleton story through diligent searching. Starting with basic keywords in newspaper archives, he refines and moulds his searches (which he keeps secret as the tools of his trade), eventually drilling down through the decades of archived material until he hits paydirt. Which in this case was In Deadly Peril, a festive ghost story set against the backdrop of a Derbyshire coalmine. It’s a story that had not been read since it appeared in a Leeds newspaper in the 1900s before being forgotten.

The secret weapon of the Tales of the Weird ghost story hunters is the British Library itself. Its headquarters in London’s St Pancras and huge archive in Boston Spa, West Yorkshire, stores a copy of every book and periodical printed in the UK. Once the ghost story hunters find a whiff of a lost tale and a book or magazine it might have been printed in, they can request a copy be brought up from the vaults.

It all sounds enticingly eerie: digging out ancient books, blowing the dust off them and revealing hidden treasures in the dimly lit bowels of a museum. The reality, though, is a little more prosaic. “It’s a bit more modern, with temperature-controlled shelves and robots that find the items,” says Tales of the Weird editor Rufus Purdy. “But sometimes you [still] get to go [and] open a book that nobody has looked at since it was placed with us a century or more ago.”

The series is in rude health, with 68 volumes so far and well over a thousand subscribers. “I think when this started off, people wondered if there would be a market for it outside of a niche interest group. But it became a word-of-mouth success,” Purdy says. “People would get the early volumes and share them with friends, and then demand just took off.” So popular is Tales of the Weird, in fact, that a two-day festival was held at the British Library in London in November for the growing army of fans.

Ghost stories are for life, not just for Christmas, but Purdy believes there’s something special about spooky tales as midwinter approaches. “Christmas is a time for telling stories of any kind,” he says. “Nowadays, that often involves TV or movies, but it used to mean sitting around the fire telling tales. What’s better on a cold winter’s night than a ghost story?”

The existence of these tales was as fleeting and ethereal as the phantoms they often featured

The existence of these tales was as fleeting and ethereal as the phantoms they often featured

We might imagine that as a Victorian custom, but the tradition goes back much further. Tanya Kirk is another of the British Library’s ghost story hunters. She worked for the institution for 16 years, during which time she became involved with Tales of the Weird, and is now librarian at St John’s College, Cambridge.

“It was my assumption that the Christmas ghost story was essentially a Dickens invention, but I worked on an exhibition for the British Library in 2014 entitled Terror and Wonder, about British gothic, and curated a section that looked at the popularity of the ghost story,” she says. “The first gothic novel was The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole, and that was published in 1764 on Christmas Eve. That, in turn, came from this tradition of scary stories being told at Christmas, which is a really ancient oral tradition.”

Kirk points out that there are even references to this custom in Shakespeare, when Macbeth sees Banquo’s ghost and Lady Macbeth says to him it’s “A woman’s story at a winter’s fire.” Kirk says: “So while the tradition of the ghost story in winter or Christmas is much older than A Christmas Carol, Dickens did bring it into the modern literary tradition.”

In 2021, Kirk worked on a volume for Tales of the Weird entitled Sunless Solstice: Strange Christmas Tales for the Longest Nights. She found the stories by scouring Christmas issues of magazines, finding one, The Blue Room by Lettice Galbraith, in the festive 1897 edition of the literary periodical Macmillan’s Magazine.

There is almost no available information on Galbraith, aside from her stories. She remains a mystery. “Depending on your situation, it might not have been acceptable for women to be writing ghost stories,” says Kirk. “There might have been family disapproval.”

Fantasy author Johnny Mains holds up his novel, Possessed

Indeed, Mains says that a huge number of the ghost stories written for newspapers were by women, often under pseudonyms. “Maybe they were writing in secret because they needed to bring in a bit of extra money for the household, but didn’t want to bring shame upon the good names of their husbands,” he says. Owing to the disposable nature of newspapers and the mystery surrounding the authors, those stories were lost and the women writers overlooked when, as books became more accessible and mass-market, ghost story anthologies began to become popular.

But not all women writers hid away for whatever social reasons. Some, such as Violet Hunt, born in Durham in 1862, positively embraced the numinous. Hunt published two collections of short ghost stories in 1911 and 1925, and her work was celebrated in a Tales of the Weird volume titled The Tiger Skin and Other Tales of the Uneasy, edited by Melissa Edmundson.

In her introduction, Edmundson writes that Hunt, a Bohemian poet, journalist and author, was “both ahead of her time and pulled by the past … independent, intellectually curious and embracing the social freedom women experienced in the beginning of the 20th century”, adding that she created “stories that explore the cruelties and miseries humans inflict on one another”.

As Christmas looms, so do ghosts as the veil between one year and the next is thinning. “The end of the year feels like a good time to take stock. People think about what they’ve done – conscience and retribution – and Dickens was absolutely playing into that,” Kirk says. “I think Christmas ghost stories are really effective because they take something that is familiar to us and comforting and they make it weird and turn it into a source of fear.”

Photographs by Alamy, Abe Books