James Fox is a British art historian, writer and award-winning broadcaster. Following spells at Harvard and Yale, he is currently director of studies in history of art at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, and creative director of the Hugo Burge Foundation, which is dedicated to supporting the arts and crafts across Britain. His latest book, Craftland, is shortlisted in the nonfiction category for the 2025 Nero book awards. He lives in east London with his wife and two children.

What first got you interested in Britain’s disappearing crafts?

It’s no secret that we are living through an industrial revolution right now, a revolution in tech and AI that is changing the way we live and work and think. So it seemed to me a very good time to look back at older ways of working and making things that themselves were transformed by an earlier industrial revolution. And I think, ultimately, it’s one of our defining traits as human beings: that we make things with our hands. So, what I’ve tried to do in the book is to write about craftspeople – who are often working in obscurity, struggling to make ends meet – with the same care and reverence as I would previously have written about great painters and sculptors.

Just how endangered are the skills – dry stone walling, coopering, rush weaving and letter cutting – that you feature in the book?

The UK used to be full of craftspeople. Every city, every town, even the tiniest little village, was full of blacksmiths and wheelwrights, thatchers, bootmakers. A quarter of these crafts are now critically endangered. In the past decade alone, five – including cricket ball making and gold beating – have become extinct. There are a number of trades and crafts that are sustained by just one surviving practitioner.

Why is it important to protect such practices? Are you just being nostalgic?

I don’t think we should be saving crafts just for the sake of it. Crafts are a vital tradition but they are also an essential part of our present and our future. We know that the act of making is extremely rewarding and can have an enormous benefit to personal wellbeing and social unity. But the craft sector also can play a very significant economic and social role. It belongs to the creative industry, which is one of the fastest growing sectors in the UK economy. It’s one of the few areas in which the UK punches above its weight. And as we try to move towards a more circular, more green economy, the craft sector models a form of production and consumption that is based on using local renewable materials, based on buying a little bit less but a little bit better, and not buying vast mountains of mass-produced stuff from the other side of the world that you then throw into landfill and replace with more rubbish.

How would you change government policy to support traditional trades?

Related articles:

The UK is one of the worst places in the developed world to be a craftsperson. Government support is woefully lacking. If you’re in Japan or South Korea, there’s something called a Living National Treasure scheme whereby the top craftspeople are actually paid by the state to pass on and promote their crafts. The French have a similar scheme. Think about how quickly they were able to rebuild Notre Dame. One of the reasons for that was because they have supported their population of craftspeople. We don’t have any schemes like that, nor do we have proper support for apprenticeships, and that’s why we face a major skills crisis in the UK.

Despite this, many of the crafts that you feature in your book are undergoing a revival. Why is that?

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The crafts are always revived during times of crisis. The first time this happened was the Arts and Crafts movement, which emerged at the end of the 19th century in response to industrialisation. You got another craft revival during the Great Depression, another one in the economic crisis of the 1970s, and we’ve been witnessing another since the 2008 financial crash and certainly since Covid-19, when many people took up crafting. What we’re living through now are obviously serious social and political difficulties, but there’s also a massive mental health crisis going on, with people feeling increasingly alienated and disconnected from the world. And it’s at times like these that we realise that working with our hands is very grounding, rewarding and reassuring.

Why do you think, as consumers, we desire things made by human hands?

I think that in a world where we can use objects that have been made by an enormous machine, there is something magical and precious about handling an object that has been made slowly, lovingly, carefully by an actual person. It connects us to the maker, and that is a very powerful experience. And if we have a handmade object, we’re more likely to treasure it, look after it and pass it on to our descendants.

Do you think there’s something we especially love about works that connect us to the land?

Absolutely. Craft has always been inextricably connected to the landscapes it comes from. A drystone wall was made with the stone that came from the field it enclosed. A rush mat would be made from the plant that grew in the local river. It connects us to the landscape in a very powerful way, which I think is very attractive in an age in which we’re trying to get closer to nature, to be more sustainable in our practices.

It is fascinating how the names and phrases associated with trades have entered and stayed in our language.

It’s extraordinary. If your surname is Smith or Wright or Mason or Taylor or Cooper or Chandler, or Dexter or Challoner, then you descend from a craftsperson. Also, specific trades have left their mark on our language. Every time you hang on tenterhooks, or you reel off some facts, or you line your pockets, or you say someone is cut from the same cloth, that is a debt to the textiles industry – and we don’t even realise it.

What do you read for pleasure?

I read a lot of nonfiction. The most recent book was Love’s Labour by Stephen Grosz, which is wonderful. I also thought David Grann’s The Wager was just the most extraordinary piece of storytelling and absolutely gripping. And I found Sarah Perry’s Death of an Ordinary Man extremely moving, honest and bracing, terrifying and uplifting in equal measure.

When did you become interested in art?

As an eight-year-old, when I was taken by my father to the Stanley Spencer Gallery in Cookham. I’d never heard of Stanley Spencer. He didn’t sound particularly promising to me, but I went, turning up reluctantly in a Superman outfit. Then I saw his painting of a scarecrow on the wall. I’d long harboured fears of scarecrows as a young boy and this was the most extraordinary image I’d ever seen. I stood in front of it for a long time, was moved to tears, and became obsessed with it, and with Stanley Spencer from that point onwards. My goal as a young person was to become a professional artist, but I was never quite good enough – nowhere near good enough, actually. So, I became an art historian instead, so that I could describe other people’s great works. The governing principle of everything I do is a love and admiration for people who create and for creativity in all its forms. It really matters: to individuals, to communities, to this country as a whole.

Craftland: A Journey Through Britain’s Lost Arts and Vanishing Trades by James Fox is published by Bodley Head (£25). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £22.50. Delivery charges may apply

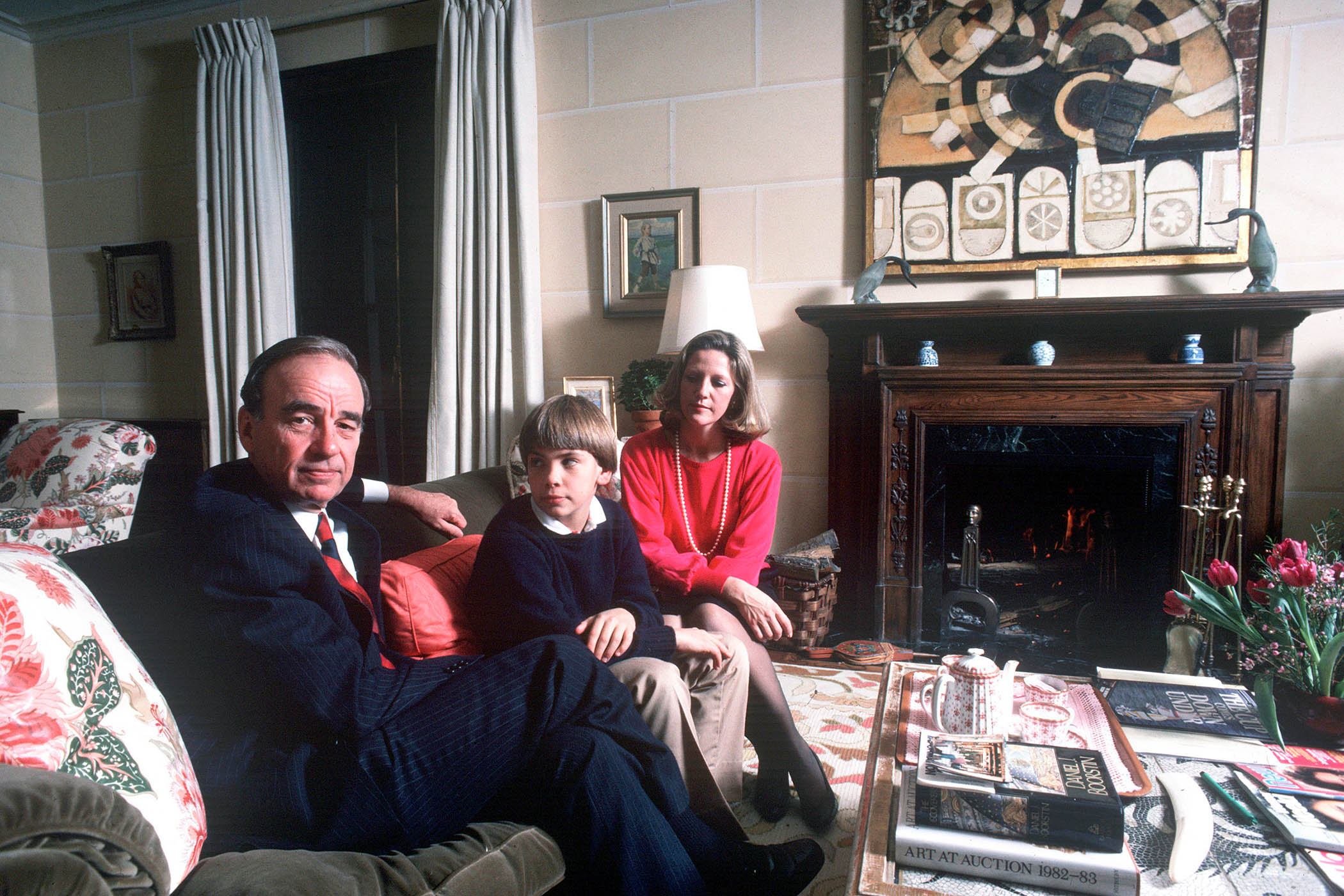

Portrait by Suki Dhanda for The Observer