Joe Sacco is an award-winning journalist who uses comics as the medium for his reportage. He was born in Malta in 1960 and raised in Australia and then the US, studying journalism at the University of Oregon. His breakthrough work, Palestine, based on his reporting from Gaza and the West Bank, won him an American Book award in 1996. His other notable publications include Safe Area Goražde (covering the war in Bosnia) and Footnotes in Gaza. Sacco’s latest book, The Once and Future Riot, explores the aftermath of violent confrontations between Jat Hindus and Muslims in Uttar Pradesh in 2013. He lives in Portland, Oregon.

What drew you to The Once and Future Riot?

A colleague in India with whom I’d worked before mentioned these riots that had taken place a year earlier, after an incident between two Jat Hindu boys and a Muslim boy, all of whom were killed. I thought it could be interesting to assemble facts but also to find out what people say about an event like that sometime afterward. In other words, what narratives they construct.

You write about uncovering the myths that take over as memories fade. Why did that appeal?

Well, a lot of journalists think what’s incumbent upon them is to tell both sides of the story and then leave it up to the reader. But I think journalists have a bigger responsibility, and that’s to get to what, for lack of a better term, is called the truth. If people tell you, “Nothing happened in this village,” well, then you find the people that something actually did happen to.

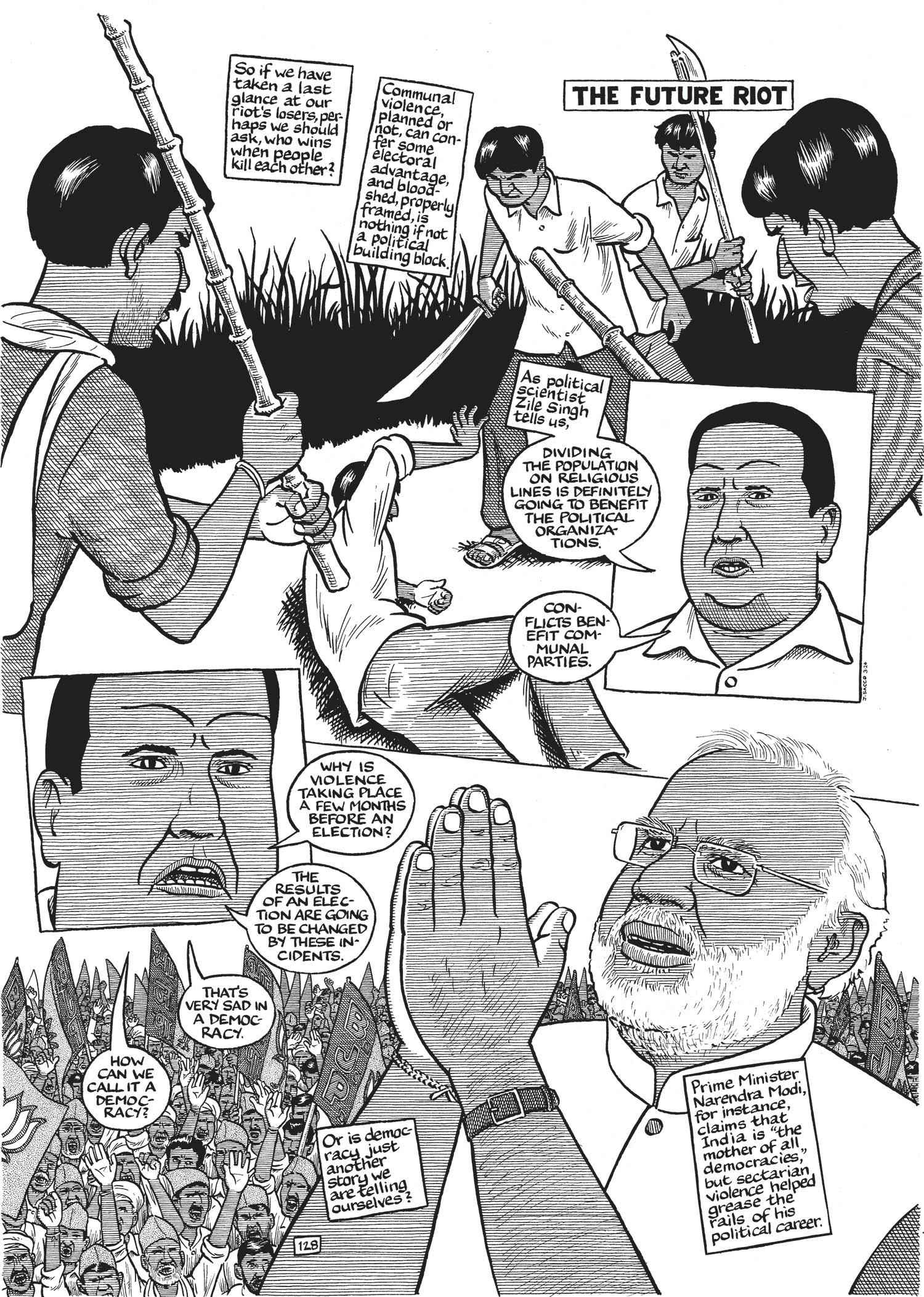

You show how politicians contributed to the violence by interfering with a police investigation, and then exploited it afterwards for their own gain. What conclusions did you draw?

The bigger issue that I began to understand was how violence and electoral politics can be intertwined. This made me question the whole notion of how we think about what we call democratic countries. I would say we’re more like electoral regimes. We live by election cycles, but politicians have become quite adept at manipulating voters to keep power. I’m a great believer in democracy. But I think there needs to be something of a democratic spirit, that we have to be involved.

You did the reporting in 2014. How long did you spend writing the book?

I wrote it immediately upon getting home. About 12 or 15 pages into drawing it, I just couldn’t continue. I didn’t really want to draw anything violent any more. And so I decided to put it aside to do a story [Paying the Land] about the Dene people in [Canada’s] Northwest Territories. After that, I returned to the India book because, in the end, if you trouble people for their stories then you need to honour that.

When did you lose your stomach for drawing violence?

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Working on Footnotes in Gaza, I remember at some point having a visceral reaction to sitting down at my drawing table. It’s strange how I decided to stop [documenting atrocities] probably 20 years ago, but it’s like an ocean liner – it’s hard to turn it around. There’s part of me that still can’t look away. I feel like I have a responsibility.

Which came first, your interest in comics or in journalism?

Comics is something I was doing since I was a child. The spark for journalism happened in high school. And so I got a degree in it. But when I got out of journalism school, there was a lot of competition and no jobs, or none that weren’t soul-crushing. So I eased out of it and fell back on drawing. I never really thought about putting journalism into comics. That sort of happened when I decided to do comics about the Palestinians, and when I was there, that journalist part of me kicked back in.

It’s such a labour-intensive method, and yet it allows you to go deeper into a story. Does it seem to you like much news coverage is just scratching the surface?

I feel like there are journalists and there are journalists. Also, as newspapers and broadcasters don’t have the income they used to, it’s a lot cheaper to have people giving their opinions than it is to have people finding out what’s going on. So I’m one journalist pushing back at another form of journalism.

In your acknowledgments, you give the sense that you’re not the most digitally literate of cartoonists.

Yeah, I’ve always been a bit behind the times. I was still using film [to take photos] when everyone advanced to digital. I was still using cassettes when people advanced to digital recording. But I really prefer to draw the old-fashioned way. I’ve made a virtue of my limitations.

You’ve threatened that this would be your last book of journalism, but you’re working on another. What can you tell me about it?

I cannot turn away from what’s going on in Gaza, and so my journalist colleague and friend Chris Hedges and I went to Egypt and interviewed people who have gotten out. We’re working on that now, and I’m focusing on one particular story, because I feel the man at the centre of it is very self-reflective. It’s kind of an epic story. Hopefully after this, I’ll hang up my journalism spurs.

You’ve been working on a book about the Rolling Stones for a long time. Is it a drag or a pleasure to go back to it?

It’s sheer pleasure. It’s like all the dots I’ve always wanted to connect. But I’m doing it in a very different way. I feel like a seven-year-old when I’m working on it. I’m giggling, I’m so happy about it.

Why the Stones in particular?

[At first because] I’m a great fan, but then I began to sort of tease out the philosophical implications of the Rolling Stones, or make them up. They’re messy, you know: they don’t have the story arc of the Beatles; they just keep going and going. And I love that about them.

The Once and Future Riot by Joe Sacco is published by Jonathan Cape (£20). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £18. Delivery charges may apply

Photograph by Celeste Noche; Illustration by Joe Sacco