Benjamin Myers is an astonishingly prolific author. His most recent novel, Rare Singles, transported us to a northern soul weekend in Scarborough; Cuddy, which won the 2023 Goldsmiths prize, was an epic experimental work tracing the life of seventh-century monk St Cuthbert. He has also published novels on crop circles and 17th-century forgers. Now, in a tour de force of literary ventriloquism, Myers focuses on one of the most controversial European arthouse figures of the late 20th century: the German actor Klaus Kinski. Artistically, Kinski is best remembered for his collaborations between 1972 and 1987 with director Werner Herzog, including the films Aguirre, Wrath of God, Nosferatu the Vampyre and Fitzcarraldo. The pair had a tumultuous relationship, as relayed by Herzog in My Best Fiend, his 1999 documentary on Kinski.

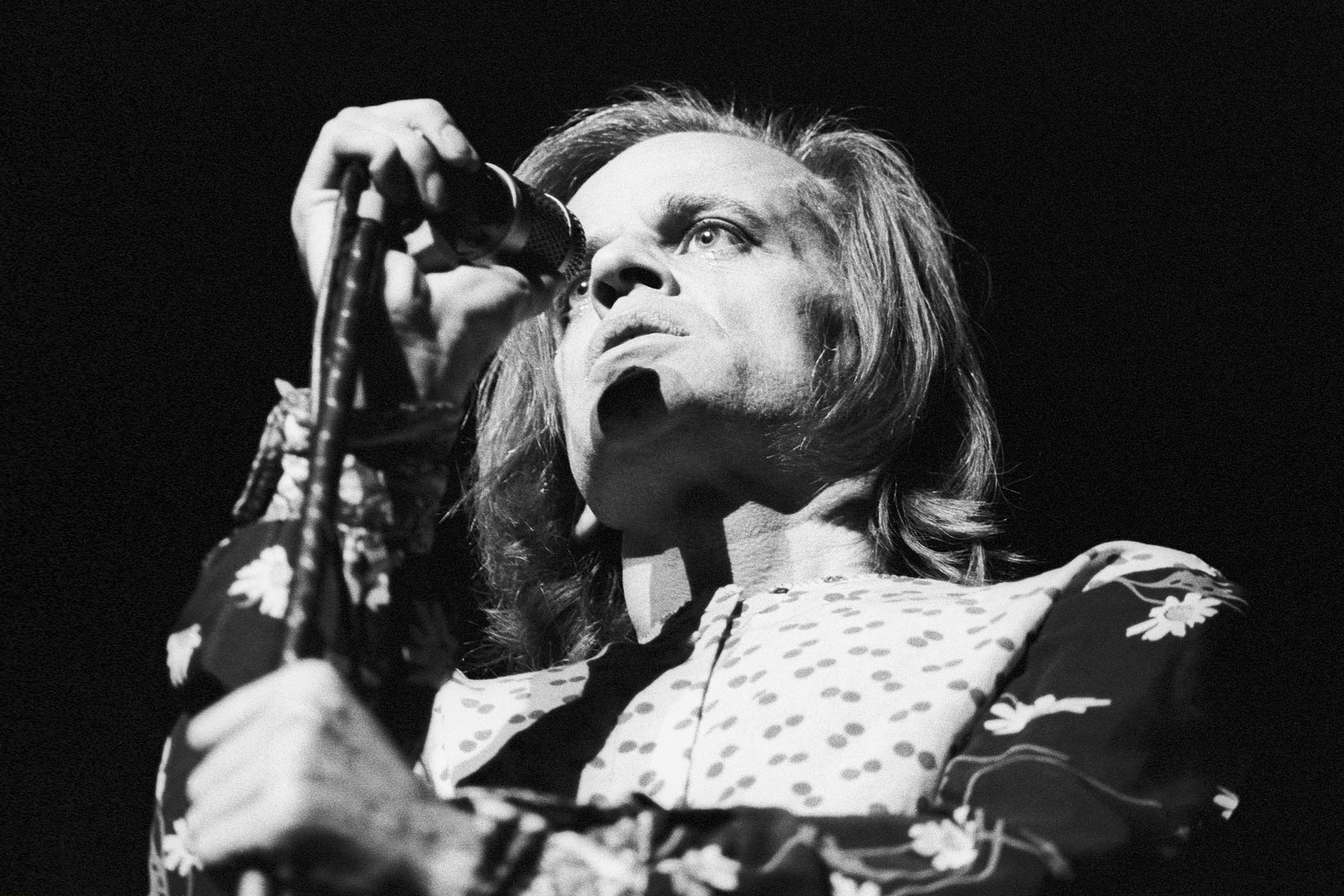

Myers opens his story on 22 November 1971, when Kinski – revered and loathed in equal measure by a public in thrall to his acting prowess and pleasurably disgusted by his notoriously vicious outbursts on stage and screen sets – is preparing to go on stage in Berlin to perform an ill-advised theatrical monologue on Jesus Christ, part of a tour through Germany and beyond. Myers gives us the full measure of a 45-year-old with long hair of (in Kinski’s words) “Viking gold”; pipe-cleaner thin but bloated with ego; dependent on drink and drugs; monstrous yet horribly vulnerable in front of a baiting audience.

“The public love an execution, especially the Germans. Love it.” Kinski’s interior voice competes with his electrifying, uber-confrontational onstage persona. He berates and interacts with the audience, in a series of pronouncements reminiscent of Hitler, before storming off in his waggling bellbottoms. There are clips available online: it’s as terrifying and compelling to watch as it must have been to witness.

The main Kinski narrative is split into Acts I and II: between is an intermission narrated by a writer in lockdown in the winter of 2021, in the quiet peace of snowed-in rural West Yorkshire. “The writer” (as he rather pompously describes himself) is, he notes, the same age as Kinski at the time of his disastrous one-man show 50 years earlier, and is obsessed with the archive film footage. Where Kinski is extroverted to the point of hysteria, the writer is a self-proclaimed introvert chasing approval and, crucially, financial stability. The writer offers wryly caustic remarks on the randomness of success: referring to a novel that became a bestseller in Germany, saving him from penury, he reflects on the “10 seconds” it had taken to decide that a major character would be German.

He berates and interacts with the audience before storming off in his waggling bellbottoms

He berates and interacts with the audience before storming off in his waggling bellbottoms

Such observations prove a fascinating counterpoint to Kinski’s own feverish insights on the public mauling that artists receive. “The critics are already gathering like jackdaws on a telegraph wire; they think you are unaware, but you see everything. You can smell them.” The novel’s argument is that in these anodyne times of virtuous youth, badly behaved male stars are a necessary jolt of energy, despite their horrific personal failings. This vainglorious self-presentation – Kinski is compared more than once to Iggy Pop – is essential to the novel’s power.

Kinski, who had been conscripted into the Wehrmacht as a teenager, derides his audience as “worthless, bearded brave-boy Berlin babies barely born when the first bombs fell on Dresden”. Following the Jesus Christ fiasco, he never worked in Germany again. He died aged 65 in 1991, an odious semi-genius who after his death was accused by one of his daughters of sexual abuse. And while Myers – as “the writer” – doesn’t shy away from these deeply unpalatable aspects of the Kinski story, his intense, double-edged fiction reminds us again of how exciting – in the right hands – the novel can be.

Jesus Christ Kinski by Benjamin Myers is published by Bloomsbury Circus (£18.99). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £17.09. Delivery charges may apply

Editor’s note: our recommendations are chosen independently by our journalists. The Observer may earn a small commission if a reader clicks a link and purchases a recommended product. This revenue helps support Observer journalism

Photography by Getty Images

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy