In the late 1990s and early noughties, Tom Paulin occupied a singular place in the British cultural landscape. He was both a respected poet and, as a result of his regular appearances on BBC2’s weekly arts programme Late Review, an unlikely minor celebrity.

Alongside the equally scholarly and combative Germaine Greer, Paulin was part of a highbrow double act, whose often highly charged differences of opinion enlivened an otherwise well-mannered forum for critical debate. His argumentativeness divided viewers and critics alike but made for riveting and unsettling viewing, as when he and Greer famously clashed over a film about the killing of 13 civilians on Bloody Sunday in Derry in 1972. When Greer expressed sympathy with the paratroopers who were responsible, Paulin accused her of talking “rubbish” and called them “rotten racist bastards”.

Paulin also rattled a few cages in academia, famously rowing with fellow poet Anthony Thwaite, whom he accused of playing down Philip Larkin’s casual racism while editing the poet’s Selected Letters. He also showed himself to be a passionate defender of Palestinian rights, publishing a contentious poem, Killed in Crossfire, in The Observer in 2001 and afterwards expressing his “utter contempt” for the “Hampstead liberal Zionists” who accused him of antisemitism.

For a time, back then, Paulin’s outspokenness threatened to overshadow his literary standing: one headline called him “literature’s loose cannon”. Against this, his 10 volumes of verse and six books of critical prose tell a different and more complex story that is rooted in his upbringing and singular political outlook.

Born in Leeds, Paulin was brought up in Belfast in a middle-class household, his father a headmaster and his mother a GP. Both his parents were members of the Northern Ireland Labour party and he once described himself as coming from “a dying breed of old middle-class, Protestant, socialist dissenters”. And though he deeply admires what he calls “the patriotism of Hazlitt, Blake and Orwell”, he is in his own inimitable way a self-styled Protestant republican, though adhering more to the 17th-century Miltonian ideal than the Irish revolutionary tradition.

Paulin read English at Hull University in the late 1960s and later wrote a paper on Thomas Hardy’s poetry as a postgraduate at Lincoln College, Oxford. Part of a generation of Northern Irish poets that included the likes of Seamus Heaney, Paul Muldoon and Ciaran Carson, Paulin came of age politically in the early years of the Troubles. “I originally thought that the state was capable of repealing itself,” he told me in 2002. “Then, I began to realise that it was not.”

A different kind of epiphany occurred much earlier, when, in adolescence, he read Heaney’s collection Death of a Naturalist (1966). “The day it was published was for me like a public holiday,” he later enthused. “You could see a star in the sky.”

Many of Paulin’s most resonant poems grapple with the thorny nature of his troubled homeland and his place within it.

Related articles:

In his 1987 collection, Fivemiletown, the protagonist of a poem titled An Ulster Unionist Walks the Streets of London undergoes a sudden, disorienting experience of not belonging on the streets of Kentish Town, wandering adrift “like a half-foreigner among the London Irish”. Having rejected the fixed certainties of tribal identity even before he found his poetic voice, Paulin was also an outsider – albeit of a radically different kind: a self-made exile at home and abroad, whose single-mindedness and seemingly innate contrariness informed both his writing and his politics.

I and several of my Northern Irish acquaintances who were living in London in the 1980s and 90s were intrigued by Paulin and identified with him. To differing degrees, we also felt that we belonged neither here nor there, though there was something oddly liberating about that not-belonging.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

That sense of intrigue deepened when, at some point in the mid-noughties, Paulin seemed to suddenly disappear from view. The long creative silence that ensued has finally been broken by Namanlagh, a new collection named after a lake, or rather lough, in his beloved Co Donegal. It is quite a comeback, and has just been acknowledged as such by the judges of the 2025 PEN/Heaney prize. In selecting it as the winner, the panel praised its spareness and the often raw power of Paulin’s language that “sings like the real hard stuff”.

Paulin’s most resonant poems grapple with his troubled homeland and his place within it

Paulin’s most resonant poems grapple with his troubled homeland and his place within it

Namanlagh contains a handful of ruminative poems that allude to the cause of his protracted hiatus. In the plainly titled After Depression?, he reflects on how his extended struggle with the noonday demon affected his ability to write: “... the power to think / has clean left me / no new essays or classes or lectures / come into my mind now / and only the odd poem…”

Another related poem, Nothing to Be Said, describes a creatively barren sojourn in his beloved Donegal – “long empty days with the blank page”. It culminates with the reluctant realisation that “neither this time nor this place is right for you”.

This is not-belonging of an entirely different order. Indeed, the handful of deeply affecting poems about his dogged but unproductive creative struggle, which appear towards the beginning of the book, are deftly rendered reflections on what, at the time, must have felt like a prolonged existential crisis. The first crack of light appears in the tentatively hopeful opening lines of A Question, where he seems to be speaking his thoughts aloud to himself: “Have I at last started to climb out / of the deep pit where I’ve been / this three and more years?”

The book is a resoundingly affirmative answer to that question, the moments of sombre self-reflection leavened by poems that revisit more familiar ground: the constant impasses that characterise Northern Ireland’s stubbornly dysfunctional politics; the long fallout of the conflict; the even longer fallout of the stopgap Act of Union that still binds the province to Great Britain. In one of two poems titled Decommissioning, a series of tangential images unfolds in a long, mostly unpunctuated flow that culminates with an abrupt shift of tone: “The union was always a dead end / a painted wee corner / whose two high walls / echo back No Surrender / as a pleading boxed-in command / Surrender.” This is pure Paulin, linguistically playful but pulling no punches.

Several Northern Irish poems – Drumcree Four, Portadown and David Trimble, Sketched – seem rooted in an already distant, more volatile time, the mid-to-late 1990s, when tensions rose as the state inched towards the fragile compromise that was the Good Friday Agreement. Portadown, in particular, plunges the reader back into the brutally sectarian horrors of the conflict in its visceral reimagining of the torture and murder of “two youngsters” caught up in the killing rage of a loyalist paramilitary feud. Its opening lines set the tone, while reaffirming Paulin’s eye for telling detail: “Each in his open coffin / each with a polo neck jumper / to hide the slashes…”

In contrast, his renderings of poems by the contemporary Palestinian poet Walid Khazendar are intimately observed glimpses of ordinary lives shadowed by loss and longing. Elsewhere, Paulin, like other Irish writers before him, seems acutely attuned to the idioms and speech rhythms of the place he left behind. As in his earlier work, there are moments when he relishes the disruptive vernacular thrust of English as it is spoken in Northern Ireland – “the power to think has clean left me” being one example that made me smile in recognition. Likewise, the sudden appearance of “boke” (which roughly translates as retch or vomit) in Ormeau Road and the raw, rural phonetics of “craychur” (creature) in the title poem.

What strikes me as different here is his emphasis on the healing power of the quotidian; the small everyday things that resonated with newfound meaning in the wake of Paulin’s long exile from writing – and from himself. In one short, perfectly pitched poem, The Catch, Paulin homes in on a “window-catch that caught my eye”, describing it as “ utile / with only the tight beauty of its function and nothing else”.

That could almost be a description of the poem itself, at least until it becomes ever more complex, distilling both the nature of Paulin’s creative struggle and his character. “It spoke to me in its dumbness,” he writes, “like a certain stubborn spirit / that pays no heed to those gods that try / – social self conscious – / to live only in the daylight.”

Throughout, it is the hard-won glimpses of daylight, longed for in the dark days of depression, that permeate and illuminate these spare, honest poems. In his inimitable way, Paulin, to paraphrase a line from another Northern Irish poet, sets the darkness echoing, while not quite dispelling the long shadows that for a time threatened to derail his journey. Long may it continue.

Namanlagh by Tom Paulin is published by Faber & Faber (£12.99). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £11.69. Delivery charges may apply

Editor’s note: our recommendations are chosen independently by our journalists. The Observer may earn a small commission if a reader clicks a link and purchases a recommended product. This revenue helps support Observer journalism

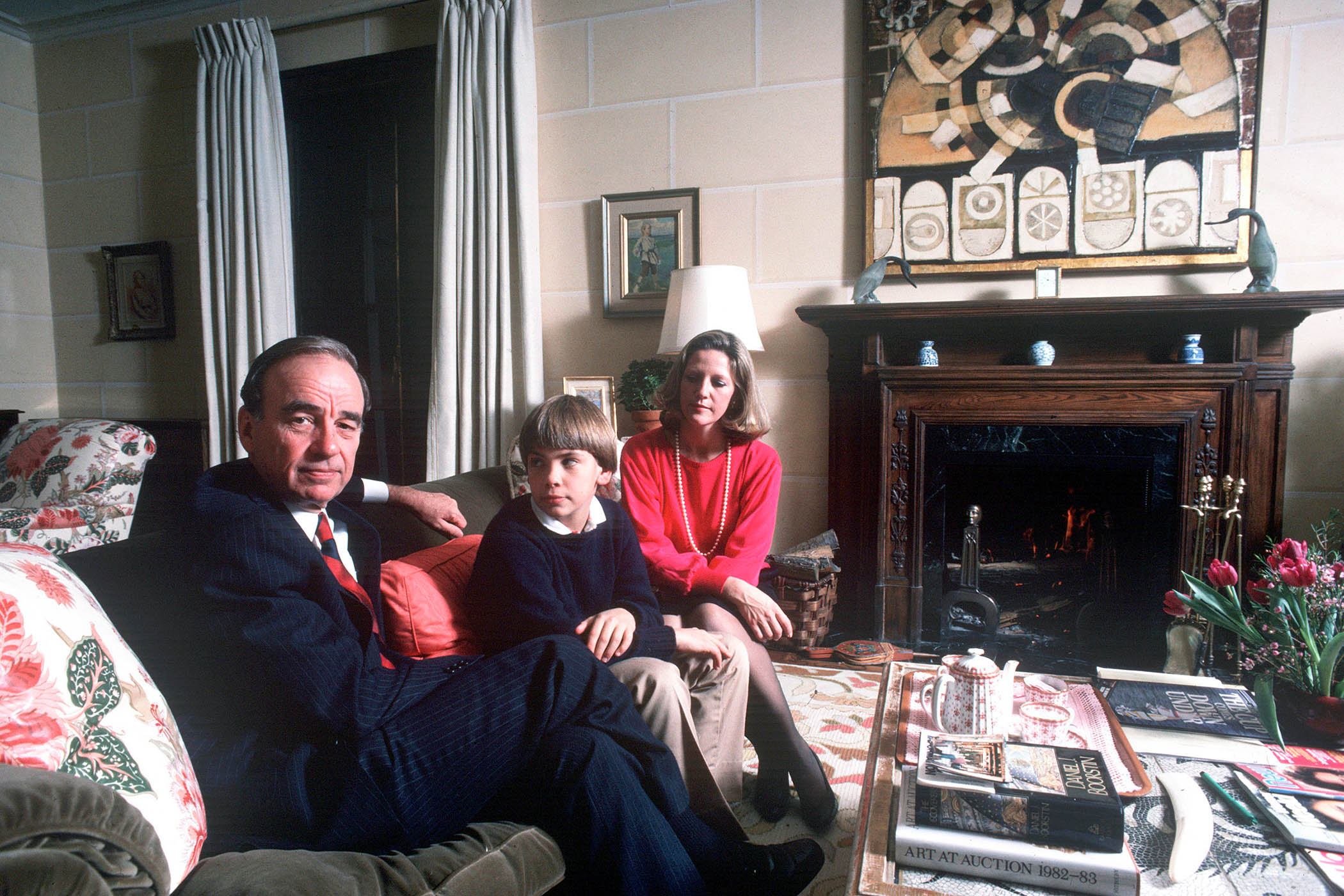

Photography by David Levenson/Getty Images